first published in Roborant Review, December 29, 2025

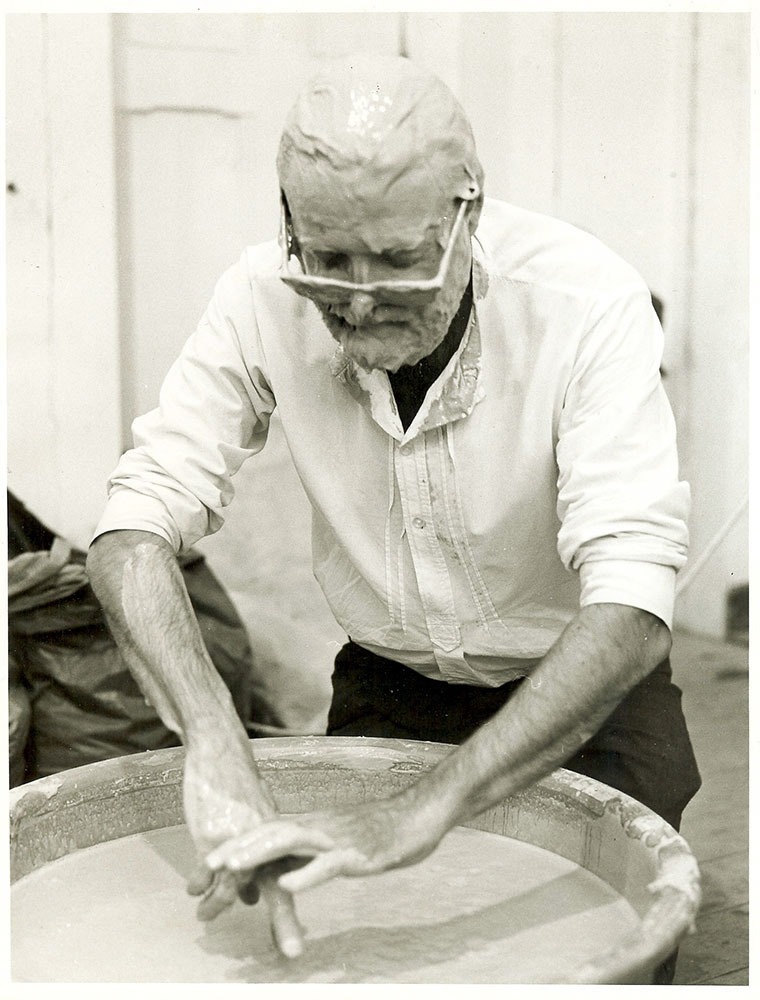

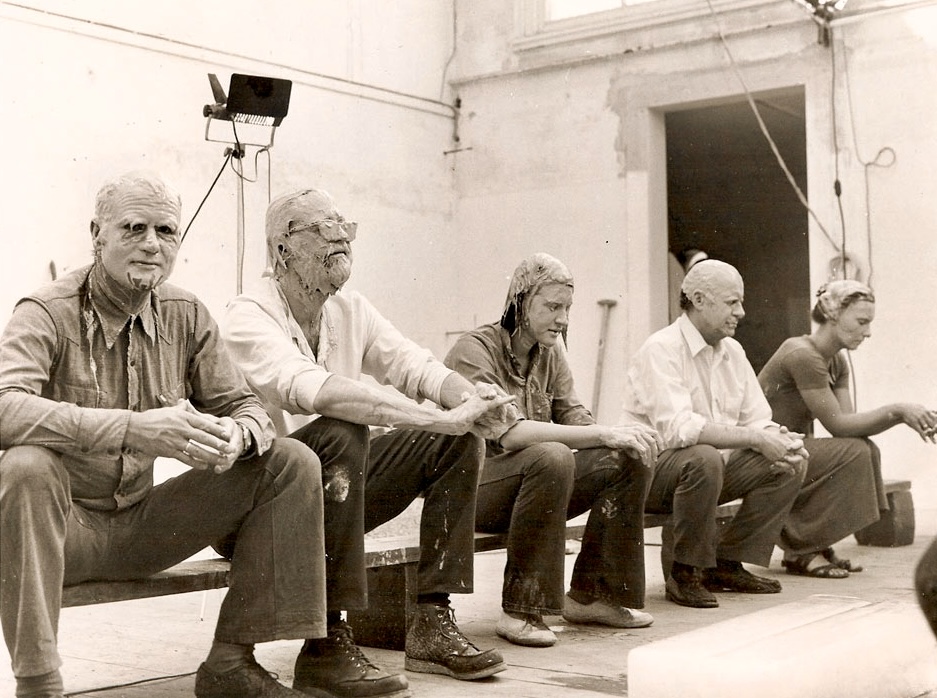

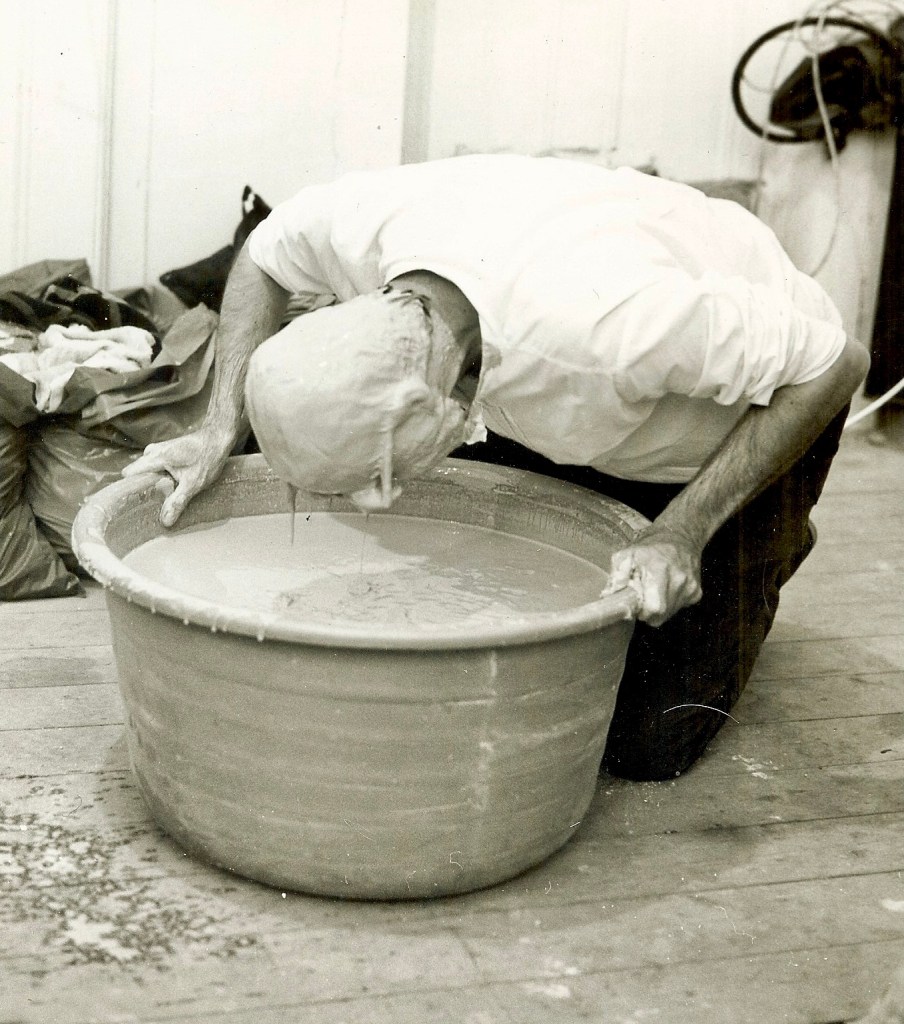

Jim Melchert after submerging his head in clay slip during his 1972 Netherlands performance piece “Changes.” Photo by Mieke Hille. (All photographs courtesy of di Rosa SF.)

Where The Boundaries Are, Jim Melchert at di Rosa SF

by Matt Gonzalez

“I can think of many reasons not to envy artists, but seeing Jim Melchert’s work makes me wish I had something comparably tangible, elegant, and smartly realized to show for my time.” –Kenneth Baker, San Francisco Chronicle, July 2011.

Multi-dimensional artist Jim Melchert, who died in 2023, is best known to contemporary audiences for the broken ceramic tile series he worked on for the last three decades of his life. This work took on shifting forms and evolved, yet remained rooted in many of the themes he had explored in the previous decades. The variety of work he produced included ceramics, site-specific installation, performance documentation, drawing, sculpture, film, photography, assemblage, and various collaborative projects within each medium. He transcended genre specificity while exploring consistent ideas about fragility, transformation, and the relationship between destruction and creation. Specifically, he was engaged with the nature of form and how when broken or shattered, it could be reimagined and recast into something new and beautiful. Improvisation and play were integral to his process.

In the early 20th century, many artists explored found objects, our relationship to them, and how they could be reconfigured into something new. The Synthetic Cubists introduced materials like newspaper clippings and fabric into their paintings; Dadaist included photographs, panes of glass, metal pipes and manufactured objects such as bicycle wheels. By mid-century, when Robert Rauschenberg coined the term ‘Combines’ to describe the paintings he made which broke down everyday objects and combined them with other three-dimensional things to create new, largely sculptural works, the delineation between mediums was well on its way to being obliterated.

Jim Melchert, Untitled, glazed ceramic, 1968.

Melchert too ignored this margin. The retrospective exhibition at di Rosa SF, curated by Griff Williams, begins by presenting some of Melchert’s earliest known ceramic and assemblage pieces including Slow Boat (1962). Melchert who had famously recoiled in repugnance when he first saw Peter Voulkos’ ceramic work (while teaching art at Carthage College in Illinois) which twisted and mangled ceramic works, later studied with him in Missoula, Montana and served as his studio assistant at UC Berkeley in the late 1950s (while pursuing an MFA). Unlike Voulkos who was distinctly clay-focused, Melchert was more aligned with many of the West Coast Beat artists, such as Bruce Conner and George Herms, who were firmly rooted in utilizing found materials. Slow Boat reflects the hybridity of his practice, combining clay, wood, and lead in a purposely vague composition. Melchert allowed the materials to speak to him, presenting an abstraction, yet also forming a minimalist and somewhat raw male form. Regardless of his intention, the way the materials articulate and suggest meaning through form and textual presence, combined with the associations our minds create, resulted in multi-material artworks that pushed boundaries for viewers.

Jim Melchert, “Slow Boat,” assemblage of clay, wood, lead, and paint, 42 x 20 x 8 inches, 1962-1963.

Addition views of “Slow Boat” by Jim Melchert.

In Slow Boat, Melchert wasn’t highlighting urban decay and renewal like many of the Beat artists or densely populating a composition with metal parts like Kurt Schwitters. Rather, he was creating a supple and surprisingly elegant form which evokes themes of absence and presence though a composition involving the dismantling or breaking of source materials, regardless of the artists’ role in that process. The early work only hints at what would become a mainstay for Melchert where he employed, not violence per se, but an act of shattering that is a catalyst for creativity and commentary. This early work highlights concerns with the purposeful disruption necessary to reimagine the ordinary. Awareness of originative structural integrity is critical to later attainment and yields a select understanding of fragility, impermanence, and the cycle of creation. When something broken is appropriated, we’re challenged to look at it differently. First, we take notice anew, imagining how it once was utilized, and when assessing its transformation, we come to terms with something beautiful emerging from what we considered familiar or ordinary.

Jim Melchert, Untitled, clay, chicken bone, fabric, feather, and wood, 1960; Jim Melchert, Untitled (Ghost Table Piece), glazed ceramic, 1965; Jim Melchert, Untitled, wood and metal, 1963.

A dynamic interplay between the broken and newly constructed pieces, and the finished constructed form, comes to life. The nature of change and possibility of renewal are implicated. Melchert shows us that there is unexpected beauty in alleged brokenness, in rawness.

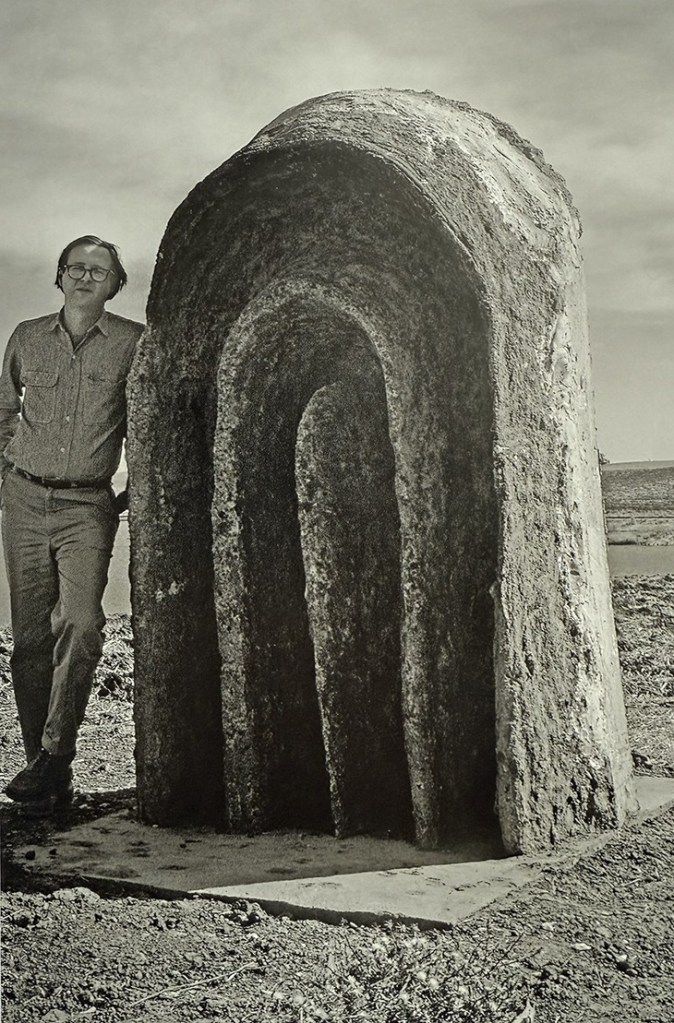

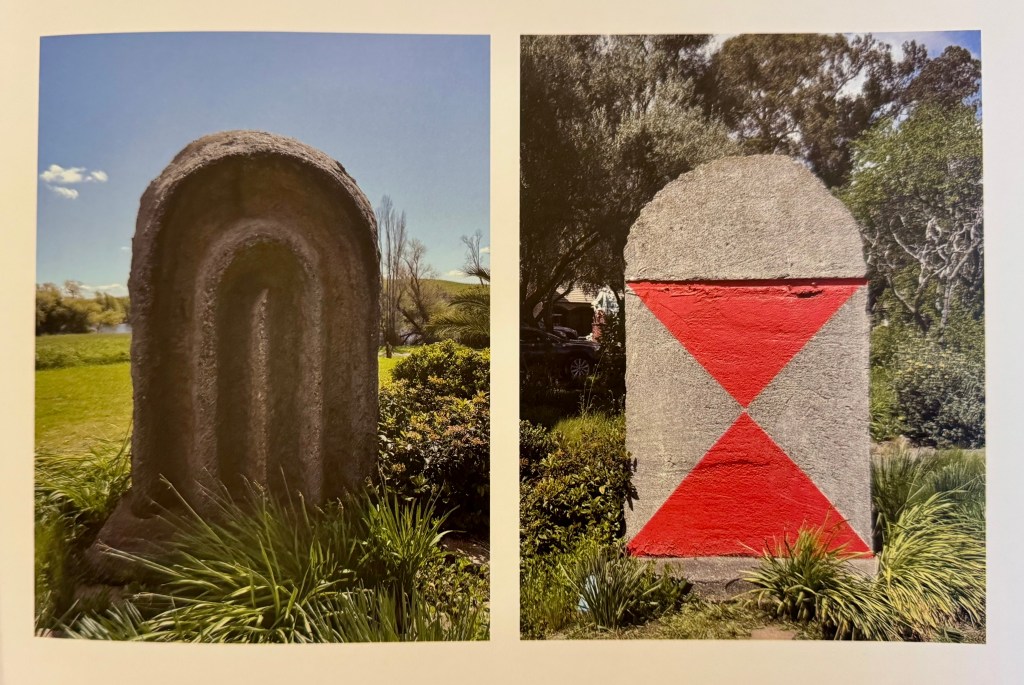

This commitment to rawness is best exemplified by Melchert’s land-art sculpture Earthdoor (1965) located at the di Rosa Preserve (now the di Rosa Center for Contemporary Art) in Napa’s Carneros region. Rather than assemble materials for the project, Melchert dug a trench into the land, making a mold he later poured concrete into, casting a nine foot tall site-specific monument. Once cast, the U-shaped piece was lifted upright. The sculpture itself remains in Napa but is represented in the exhibition through photographs and other ephemera related to the project. Importantly, Melchert finalized the piece by rendering two hand-painted red triangles on one side, set atop one another to suggest an hourglass, embellishing it with just enough of the human hand to offer a personal imprimatur of authorship, thus collaborating with the earth’s soil which had hugged the form into shape. The pattern itself, a deeply grooved surface, referenced the freshly plowed fields which were set to become vineyards in the nearby area, yet the piece itself conveys a primitive quality as if it were a monument of some kind. The texture and scale make it seem right out of Stonehenge or the Megalithic Temples of Malta. It easily could be an entryway or some type of edifice for a prehistoric site with painted triangles on its side, offering cautionary signage about how our lives are intertwined with the environment, and how we are always in collaboration with our milieu and its placement in time.

Jim Melchert, “Earthdoor,” concrete and paint, approximately nine feet tall, 1965.

The use of materials on hand suggesting improvisation also concealed the thoughtful and careful intention that preceded some of his work. In 1972, while participating in the prestigious Documenta 5 exhibition in Kassel, Germany, Melchert visited Amsterdam and performed Changes in the studio of artist Hetty Huisman. He assembled nine other participants, all Dutch artists, who immersed their heads in a bucket of ceramic slip. They were thereafter directed to sit upright on a bench in a linear group for an hour. The grey color liquid, whose viscosity kept it from simply dripping off, slowly congealed and hardened.

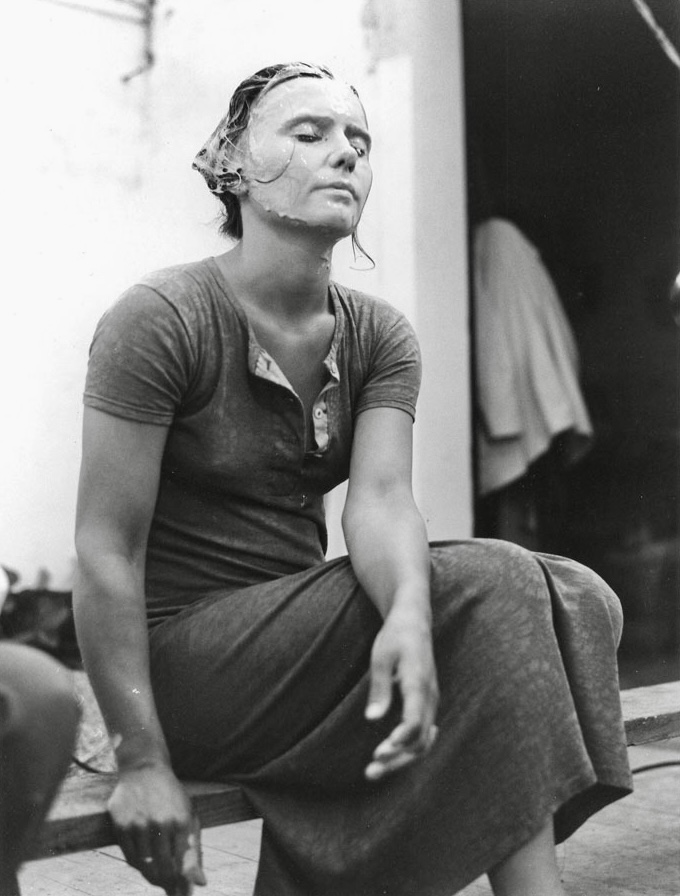

Aside from the visually striking grey-scale quality of witnessing the scene, Melchert was making a living sculpture about what the artist felt. The viewer witnessed one thing while the artists endured another. The viewer’s experience, one where disruption of normalcy is highlighted by a seemingly absurd act, combined with the meditative process for the participants as the slip dried and encased their heads in a vessel, of sorts, draws attention to how the artistic experience can differ for maker and audience. Melchert later described the sensation he felt:

“It encases your head so that the sounds you hear are interior: your breathing, your heartbeat, your nervous system. It is surprising how vast we are inside. What I realized was, by sitting there with the other people with my ears and eyes blocked, I was experiencing my interior.”

Photos from the performance ‘Changes’ (1972)

The slip acted as a mask, which when coupled with Melchert’s foreign status as an outsider, also posed questions of how we relate to one another and how we build trust outside of our geographic communities; here one can feel the camaraderie of artists regardless of place and the agreement to serve as participant/collaborators, which also defined much of Melchert’s life as an educator and mentor.

The melancholy visages prompted by the dull-colored slip also alludes to contemplative forms such as Auguste Rodin’s bronze Burghers of Calais (1884-1889), where the figures are grouped together in a communal act, yet display something very un-heroic; a fatalism and acceptance of their situation. With the Changes participants this effect resulted from being directed to sit and remain still while the clay hardened, yet the visual experience for the viewer projected a near frozen indifference, sparking curiosity as to whether they would get to see something more happen.

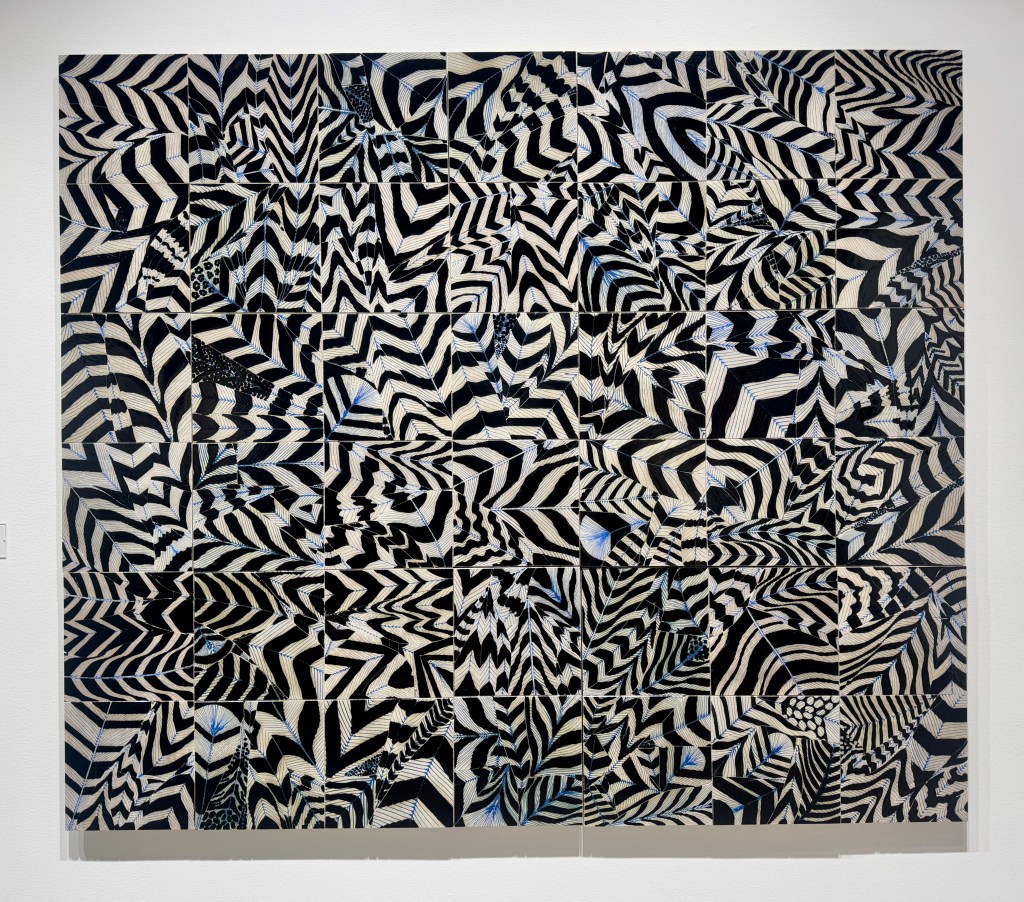

Jim Melchert, “Feathers of a Phoenix” (Blue), broken and fired porcelain tile with glaze, 2003-2004.

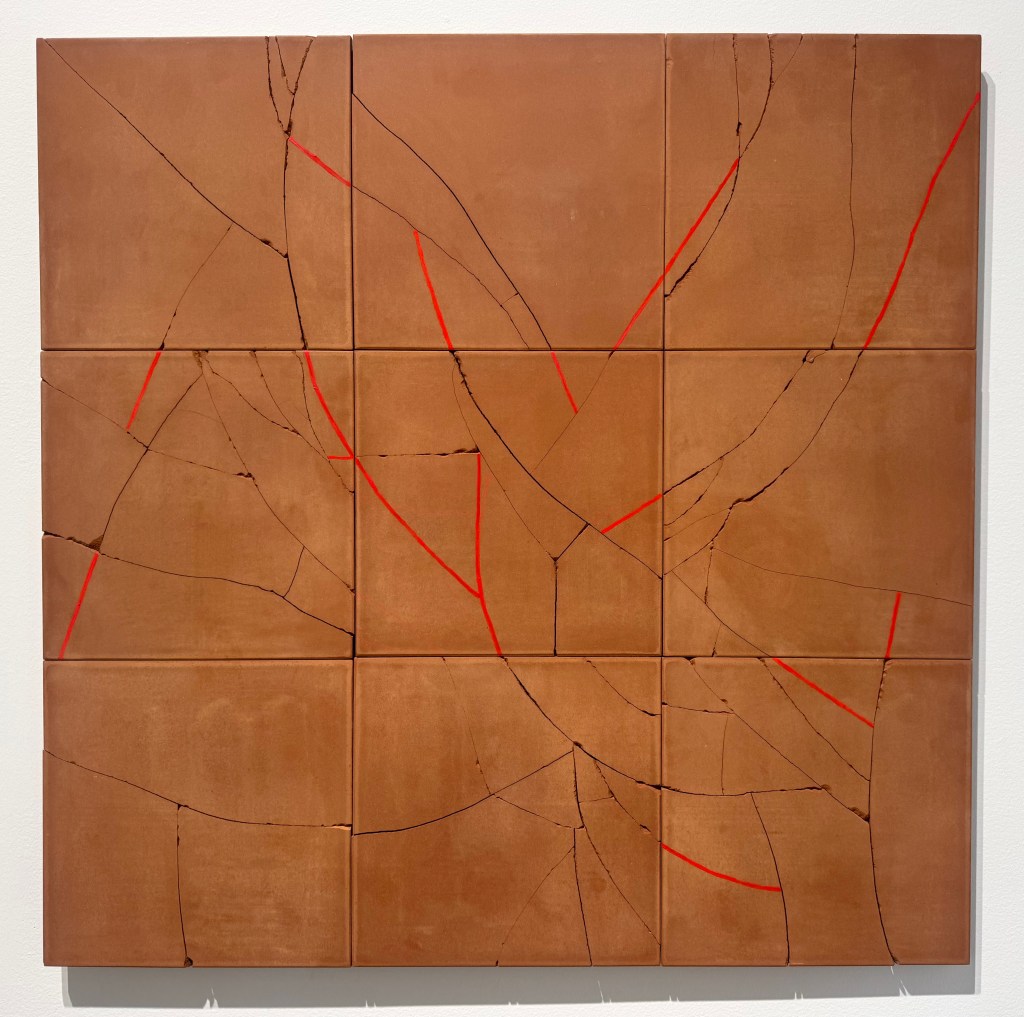

In the mid-1980s, Melchert began exploring the use of ceramic tiles, first simply assembling them outside of their intended sequences using patterns that referenced alternating electrical current. Later he veered toward the re-assembly of broken tiles. He used commercial porcelain floor tiles, broke them against the ground or other hard surface and thereafter reassembled the pieces into their original orientation as a square. He would embellish them with paint and glaze along the cracked edges, drawing attention to the very fractures that should cause the viewer to see something broken. He also built up the surface in places, with more tile fragments, and often made repairs that guided his painting and glazing compositions as if he were drawing. The finished works are striking in how a broken object projects a newfound beauty because of guided manipulations.

Melchert’s work with tiles was sparked by his travels in the Middle East in the 1980s and the four years he spent teaching English in Sendai, Japan, which served as his alternative service as a conscientious objector during the Korean War. Melchert must have become acquainted with the Kintsugi tradition, where broken pottery is repaired using lacquer mixed with gold, silver, or platinum. Significantly, the technique highlights a vessel’s fractures, celebrating rather than concealing its previous damage. Dating back to the late 15th century, Kintsugi assimilates the aesthetic idea of wabi-sabi, which exalts beauty in imperfection, and the Buddhist concept of mushin, which embraces fluidity and non-attachment. The kinship with Melchert’s own practice is manifest.

Jim Melchert, “Desire as Terrain,” broken and fired porcelain tile with glaze, 1996.

Detail of “Desire as Terrain.”

Yet, in contrast to Kintsugi, the repairs Melchert made through his practice aren’t really mending the pieces at all; certainly not to further any traditional functionality. In essence, he had a situation on his hands that he then worked to resolve visually and aesthetically. Rather than view his act as repairing, he saw growth and something altogether new in how it could activate visual sensation. He embraced the moment of crisis, as he deemed necessary, usually by engaging in a conversation with the fragments, which directed Melchert’s actions. Melchert perceived his work as more than simple art-making; it stood for how unexpected things happen in life, and how pivoting to deal with them ultimately defines you.

As curator Griff Williams noted: “We see in his late tile work a metaphor for life. What lies behind these broken shards in Melchert’s mesmerizing works is something remarkable: Optimism. Nothing is beyond repair. These works are born from the belief that we have the power to bring positive change from our misfortune. By embracing the imperfect, he was celebrating our resilience, diversity, and human strength.”

Jim Melchert & Galen Melchert, “The Move That Won the Game” (Jim’s Final Tile), broken and fired porcelain tile with glaze, 2023.

The cycle of life, represented by broken and remade elements, repeat in a cycle that captures the essence of a healthy life. Hardships and triumphs invariably recur. Melchert successfully blurred the lines between repair and new; between restoration and reinvention. His was a thoughtful engagement with destruction. He broke things intentionally, knowing how not to create too many shards. Clearly not random, spontaneous, and not found. But rather, chosen and directed. Melchert liked to say that he was creating a “situation” that needed fixing. He welcomed that challenge.

Melchert’s broken ceramic tile work was complicated and varied. He sometimes used a preselected set of rules. He also invited studio visitors to repair broken tiles with as little masking tape as possible, thereafter glazing the non-repaired sections (as in “Min Nguyen Repair Series #1” (2003)). In a series named after places he had visited, Melchert would adhere blue bands of color tracing the tile’s fracture, building up the surface with stacked tiles (as in “North Atlantic” (2005)).

Jim Melchert, “Estate No. 101,” broken and fired porcelain tile with glaze, 2023.

Jim Melchert was an artist who explored the transformation of things that already exist. He was interested in form and how it could be changed purposely while still retaining elements of its original nature. That process exemplified his engagement with life and how he explored the myriad of ups and downs that naturally confront us all. His artwork is an invitation to embrace rather than recoil from adversity or pain. He showed us that beauty could be remade from sharp fragments and a visually engaging concept was always within our grasp, if we just embraced the situation and looked at the promise of destruction. The latter was an opportunity that invited ingenuity. New forms could rise up from old ones as easily as they were broken. This was the essence of his art.

The exhibition includes many other facets of Melchert oeuvre including drawings, early ceramics sculpture, and intriguing video collaborations. The exhibition spans six decades and includes over 60 separate artworks. Additionally, the first monograph on Melchert’s career, a 256 page fully-illustrated book with critical essays by various authors, Jim Melchert: Where The Boundaries Are (San Francisco: Gallery 16 Editions, 2025), edited by Griff Williams, accompanies this important exhibition.

–The End

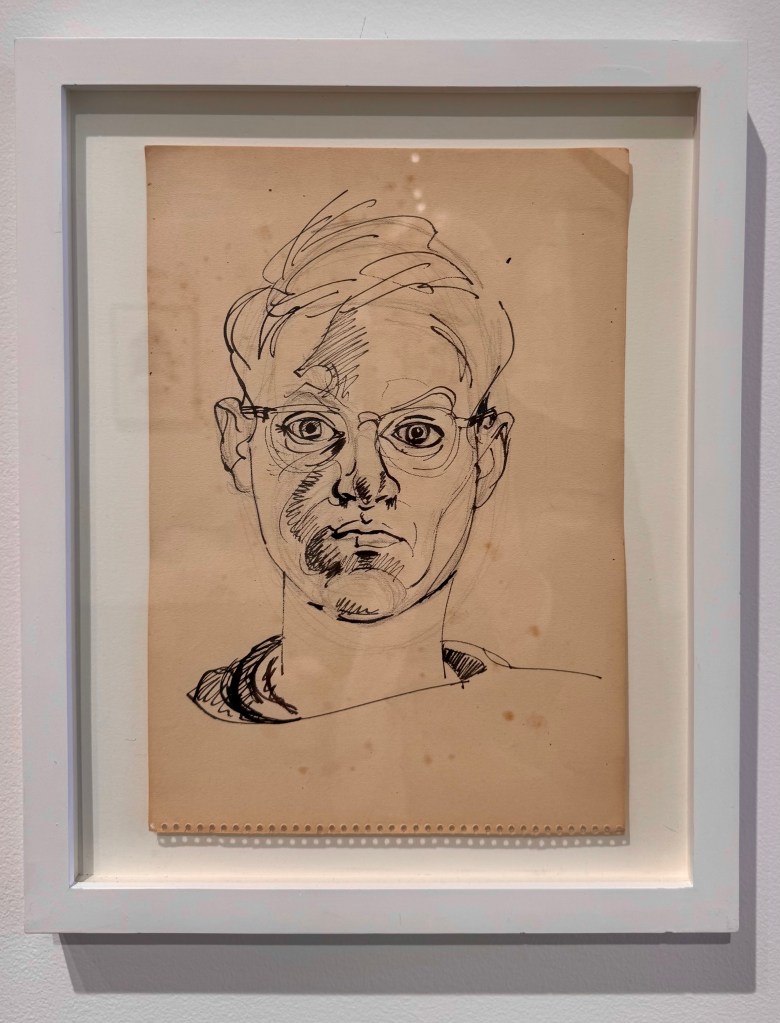

Jim Melchert, “Self-Portrait,” ink on paper, 1949.

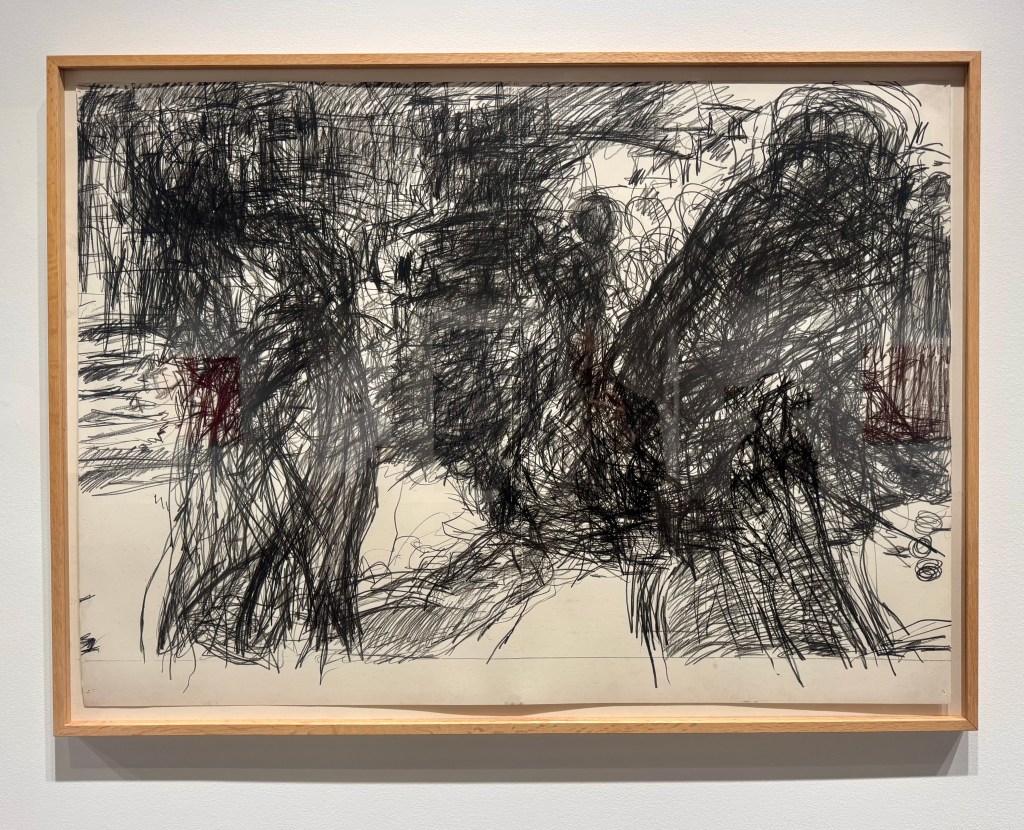

Jim Melchert, “Tibet,” black conte on paper, 1985.

Jim Melchert, “Grotesque a,” earthenware, low fire glazes and silver luster, 1967.

Jim Melchert, “Photo Negative with Metal Ashtray,” metal, clay, and glazes, 1968.

Jim Melchert, “Porto,” glazed and layered porcelain tile, 1996.

Detail of “Porto.”

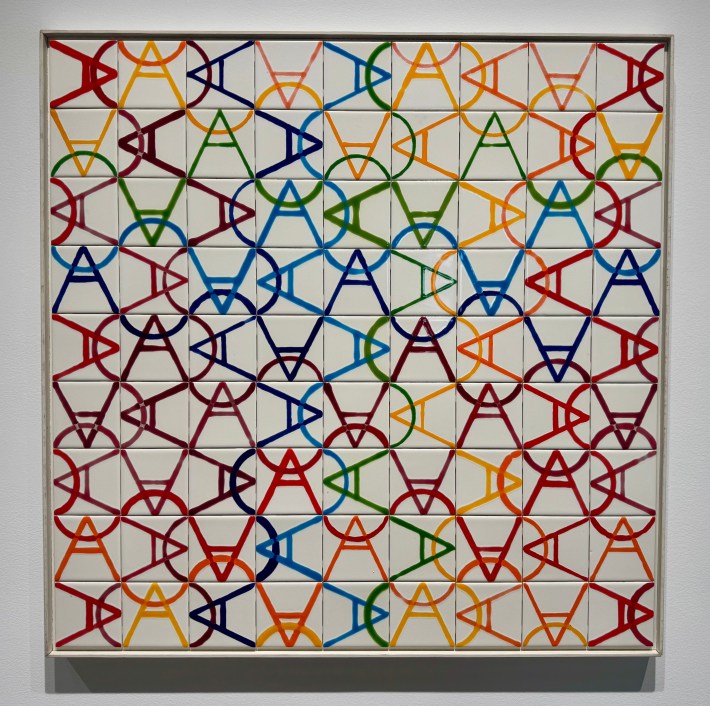

Jim Melchert, “Alternating Current #4,” fired porcelain tile with glaze, 1985.

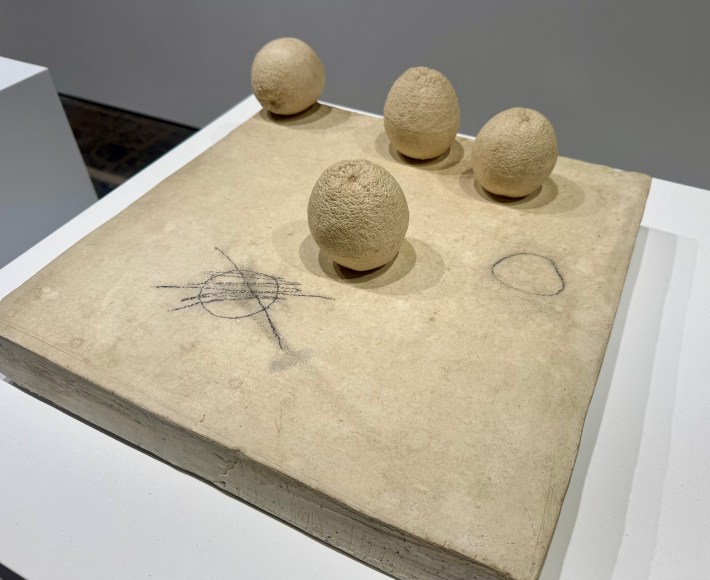

Jim Melchert, “Drawing With Red Extensions,” unglazed ceramic tile, crayon, and paint, 1994.