first published in Roborant Review, January 16, 2026

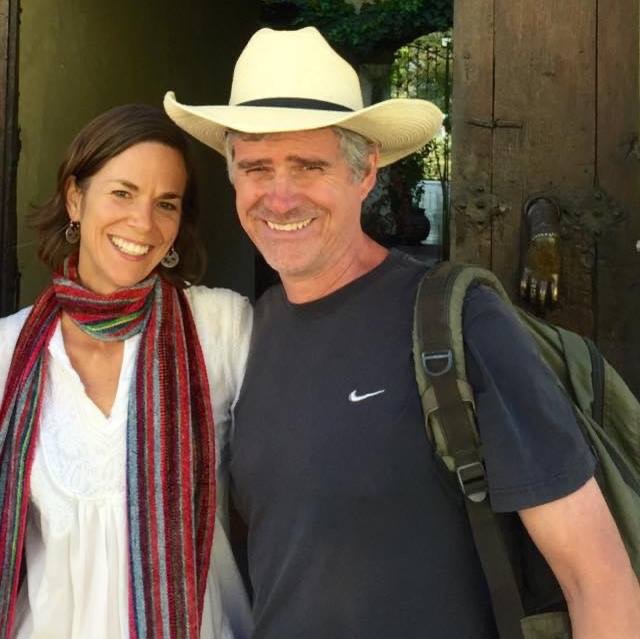

Stephanie Jolluck & Gio Rossilli

PRESUMED GUILTY

The story of how reputation and custom failed to protect two Americans falsely accused of stealing cultural patrimony

By Matt Gonzalez

In November 2022 the Guatemalan authorities issued press releases about the arrest of an American woman involved in smuggling hundreds of Mayan artifacts out of Guatemala. The media reports are sensational: “American Busted Twice in 3 Days Smuggling Mayan Artifacts Out of Guatemala” and “American Woman Tried to Smuggle 166 Maya Objects From Guatemala.” To any reader the actions would appear to be a gross violation of international law and an affront to Guatemalan cultural patrimony.

The legal case, as presented in the media, seemed open and shut. Stephanie Jolluck was first arrested boarding a plane to the United States at La Aurora International Airport in Guatemala City. Two alleged pre-Columbian artifacts were found in her carry-on bag. Three days later, in the city of Antigua, while in a car with her husband Giorgio Rossilli, Jolluck was again stopped, and she and Rossilli were found to be in possession of a large collection of over 100 pre-Columbian artifacts. They were accused of transporting the antiquities for illicit purposes, presumably for export out of the country. Readers of these media accounts were not given any other possible narrative to contextualize what had transpired. Thus they were understandably concerned about the alleged trafficking of national treasures. The only problem was the allegations were false.

What everyone seemed to miss was Jolluck and Rossilli’s long engagement with Guatemala. They are precisely the kinds of people who would not do anything to knowingly harm Guatemala or its cultural heritage. Both had many decades of experience working to help preserve Guatemala’s cultural history. Their years of engagement should evoke pride among Guatemalans, but these allegations have understandably raised doubts among those who aren’t familiar with their history or character.

So how and why did all of this happen? And what motivation did the Guatemalan authorities have for mischaracterizing the events surrounding their arrest? Answering this question raises issues related to the media’s failure to independently report on the story and also reveals a complicated web of intrigue between two important cultural institutions in Guatemala. What is very apparent is that media accounts, despite obvious red flags, accepted as true the official government version of what took place. Here’s what the media overlooked:

I. Everything known about Jolluck and Rossilli tells us they would not do anything to harm Guatemala

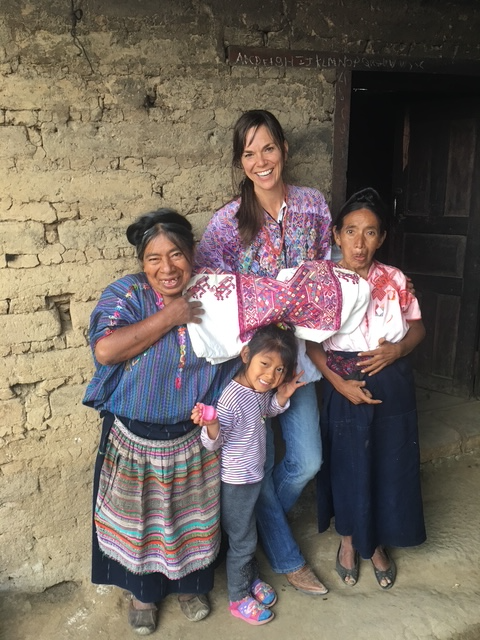

Jolluck with long time friend Justina Patzun.

Who is Stephanie Jolluck?

Jolluck spent 25 years working and travelling in Guatemala, which she considers her adoptive home. Before her arrest, she had been working in the Highlands of Guatemala with families and worker cooperatives producing textiles, accessories, and folk art. These efforts were both intrinsically valuable and served a commercial purpose which enriched hundreds of Guatemalan families. On numerous occasions Jolluck has been recognized for her humanitarian efforts: In 2013 she was awarded the “Leg Up” Female Entrepreneur Award by Spanx’s founder Sara Blakely in a program designed to spotlight female entrepreneurs making a difference; Jolluck’s fair-trade line, Coleccion Luna, was recognized for its ethical focus by InStyle Magazine; and Jolluck was profiled by authors Don Cheadle and John Prendergast as an “Upstander” in their book The Enough Moment (2010), which is a term they use to honor individuals who take significant, creative action against human rights violations and mass atrocities.

Announcement for “Leg Up” Female Entrepreneur Award from Spanx, 2013.

Jolluck’s primary work originates from the business she founded, Coleccion Luna, in March 1999 working with Maya women’s cooperatives and families in the Highland region on a line of repurposed textiles created from their gently-used, traditional handwoven clothes using fair trade practices. Her work has been cited as a model for helping indigenous Guatemalan families earn a living wage and preserve their 2,000-year-old textile traditions while simultaneously addressing the economic roots of vulnerability in at-risk communities.

Additionally in 2014, her textile expertise led her to be selected by the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia to assist in deaccessioning and repatriating Guatemalan textiles held by the museum. The archive has the largest ancient art collection in the Southeast and includes objects from ancient Egypt, Rome, Africa, and the Americas, so their vote of confidence in selecting Jolluck is noteworthy.

Jolluck has a long history of supporting various NGOs in Guatemala and Africa raising funds and awareness for their work, all of the work done pro bono. These groups include:

CARE (Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere), which is headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia, is one of the oldest humanitarian organizations delivering emergency relief and promoting international development projects around the world. Jolluck worked between 2006-2014 on projects empowering women and young girls, participating in organizing fundraising efforts for the organization. [FN 1]

Safe Passage (Camino Seguro) is an organization based in Guatemala City that provides assistance to communities living amidst the largest landfill in Central America. Their initiatives promote education for children, holistic health and wellness services, and job opportunities for adults.

Partner for Surgery is an organization based in the U.S. that provides medical and surgical care in rural Guatemala. In 2021, Jolluck used her photographic skills to help document the work of The Child Nutrition Program which specializes in cleft lip and palate surgery.

The Enough Project was a Washington, D.C. based organization (2007-2016) which conducted research projects focused on ending genocide and crimes against humanity in various African regions (including Sudan, South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the Central African Republic). Jolluck participated in organizing fundraising events in Atlanta to support their efforts. [FN 2]

We Want Peace In Sudan, a project led by Emmanuel Jal, a former child soldier, who now lives in Canada. Jolluck’s team of women in Guatemala made hand-beaded bracelets promoting the “We Want Peace” campaign and funding the building of schools in South Sudan and spreading a message of global peace. [FN 3]

As a photographer, Jolluck has taken hundreds of photographs in Guatemala capturing the beautiful essence of the country. The work shows a high degree of respect and appreciation for her adopted country, its culture, landscape, and people. [FN 4]

Jolluck’s commitment to social justice issues and specific work in Guatemala has been consistent and impactful. Since her first trip to San Lucas, Sacatepéquez, Guatemala in 1997 when she volunteered working in a co-op engaged in organic farming, herbal medicine, built stoves and latrines, and participated in leadership training to empower women who had survived decades of civil war, she has demonstrated a love for the country of Guatemala.

Gio and Stephanie

Who is Gio Rossilli?

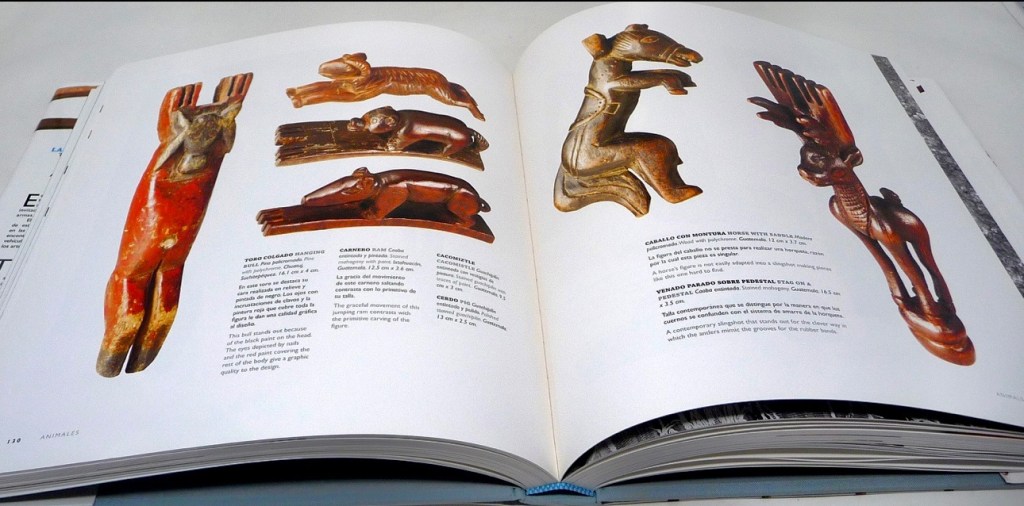

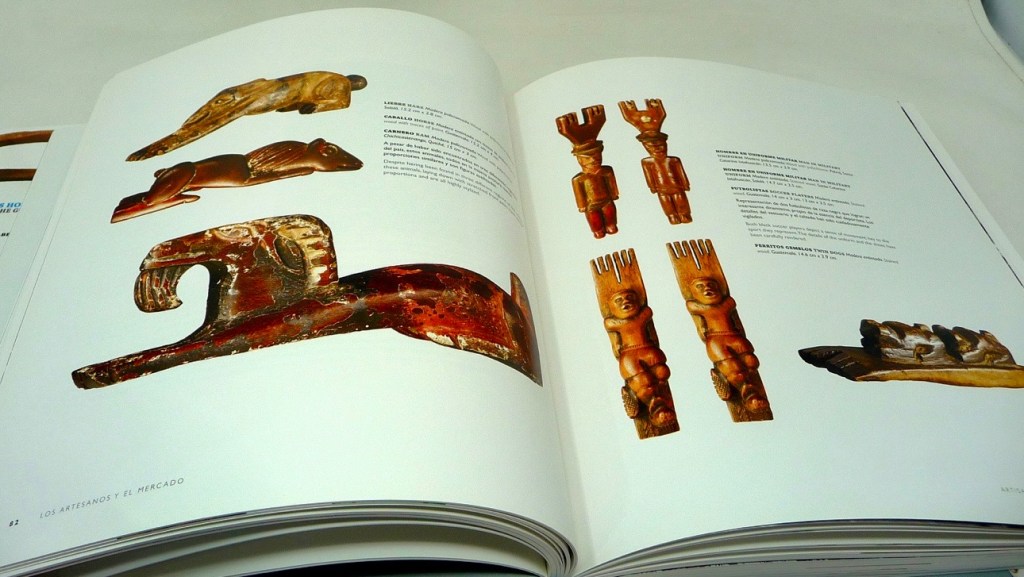

Gio Rossilli has spent the last 30 years living and working in the Highlands of Guatemala studying, researching, and helping to preserve the folk customs of this region. He operated a gallery in Antigua from 1995-2001, La Eclectica, specializing in Guatemalan folk art including masks, primitive furniture, slingshots, woodcarvings, weavings, folk saints, naive paintings, and majolica pottery. This gallery helped many Guatemalans making craft arts sustain a living for their otherwise undervalued labor.

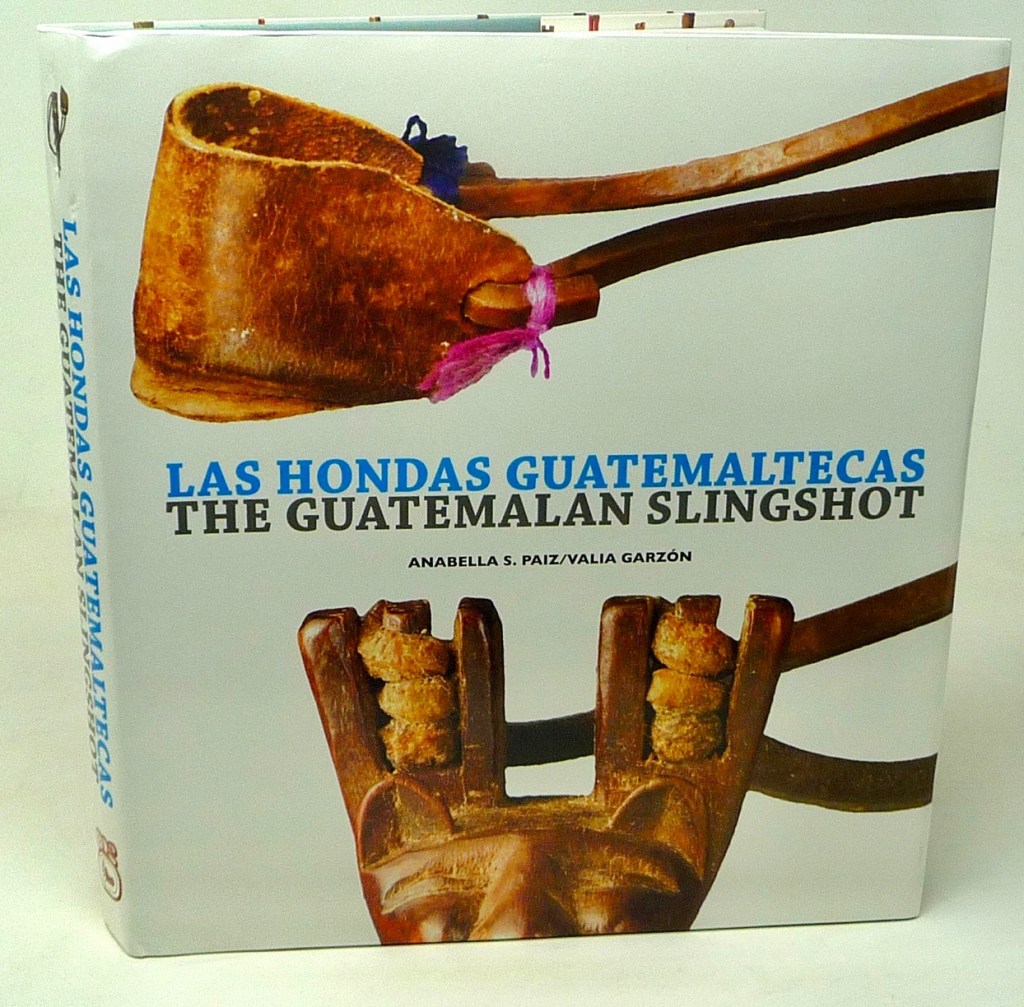

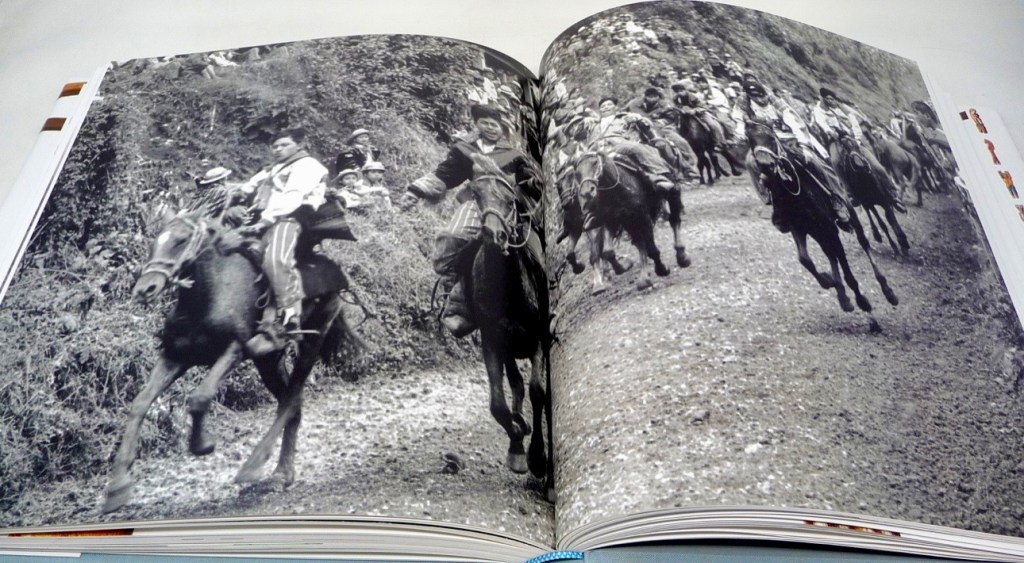

Rossilli has worked hard to preserve the cultural heritage of Guatemala. He served as the primary expert responsible for locating and authenticating works included in Las Hondas Guatemaltecas / The Guatemalan Slingshot (2007) by Anabella Paiz and Valia Garzon, which is a comprehensive 283-page book cataloging this indigenous art craft. It was a three-year anthropological project where he worked as a field guide, advisor, and researcher. [FN 5]

“Las Hondas Guatemaltecas / The Guatemalan Slingshot” (Antigua: La Ruta Maya Conservation Foundation, 2007) by Anabella Paiz and Valia Garzon.

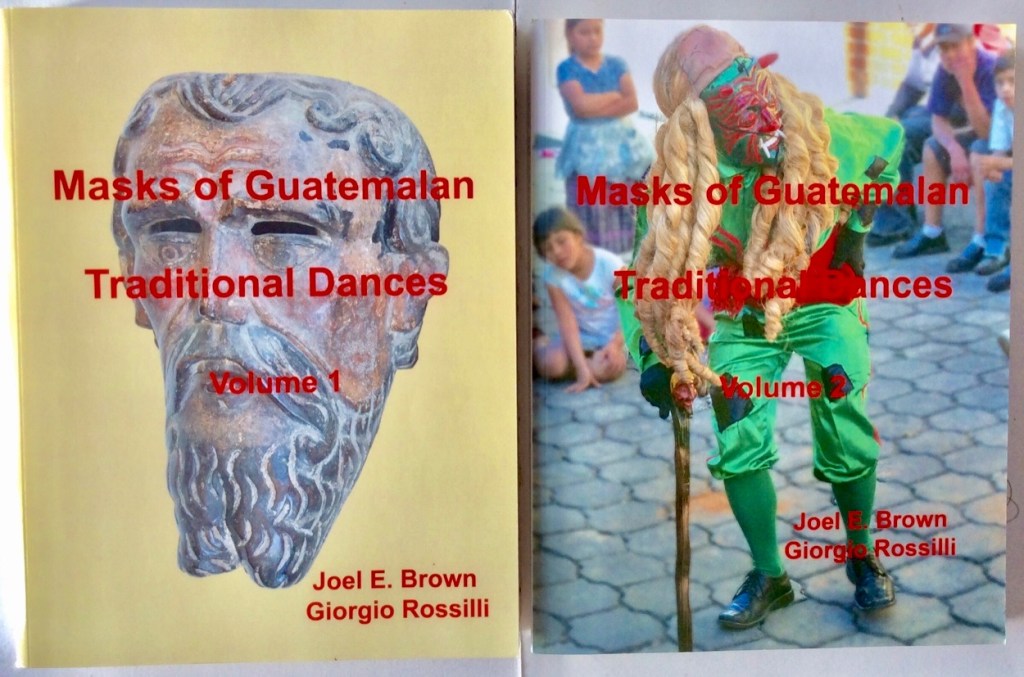

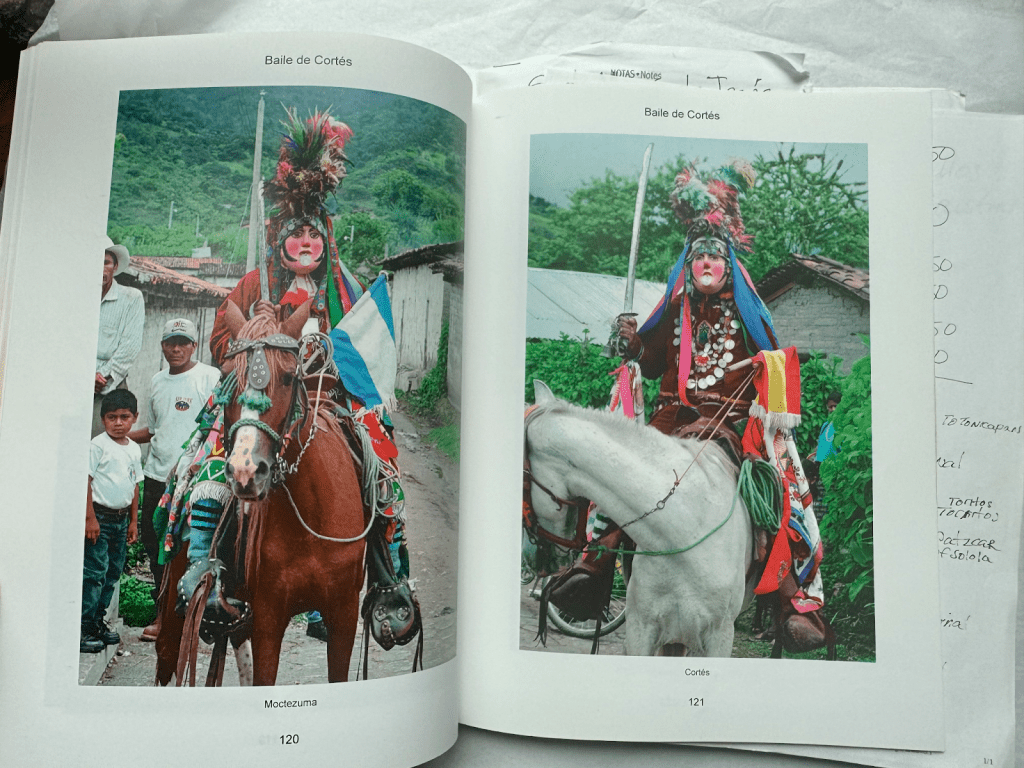

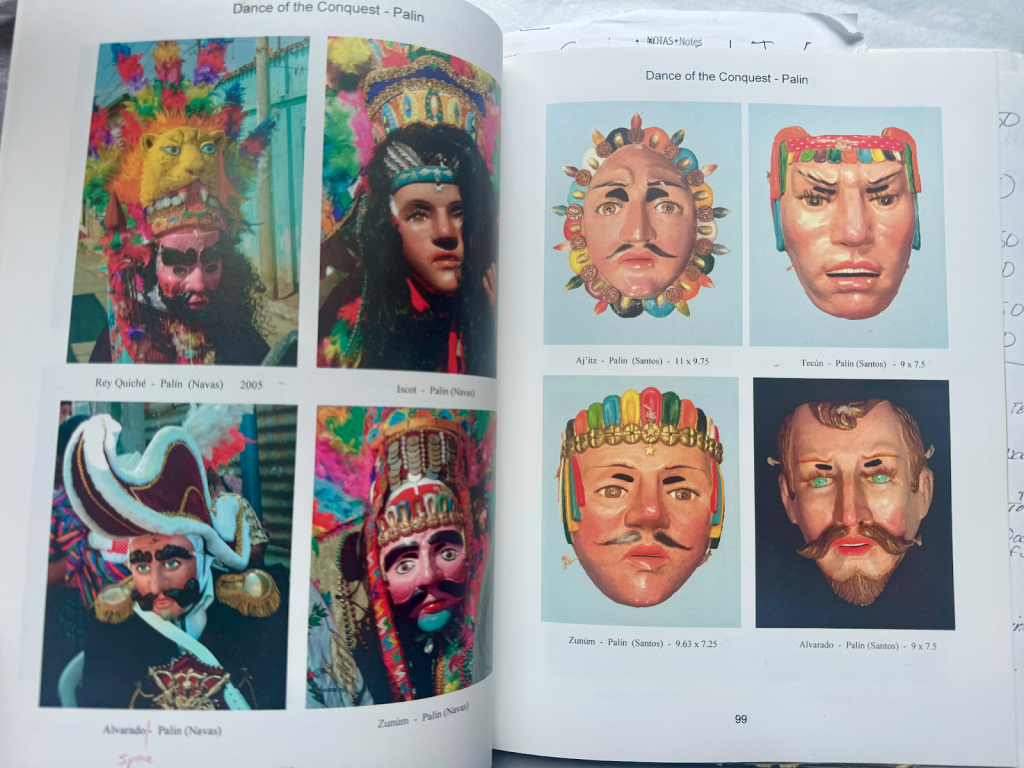

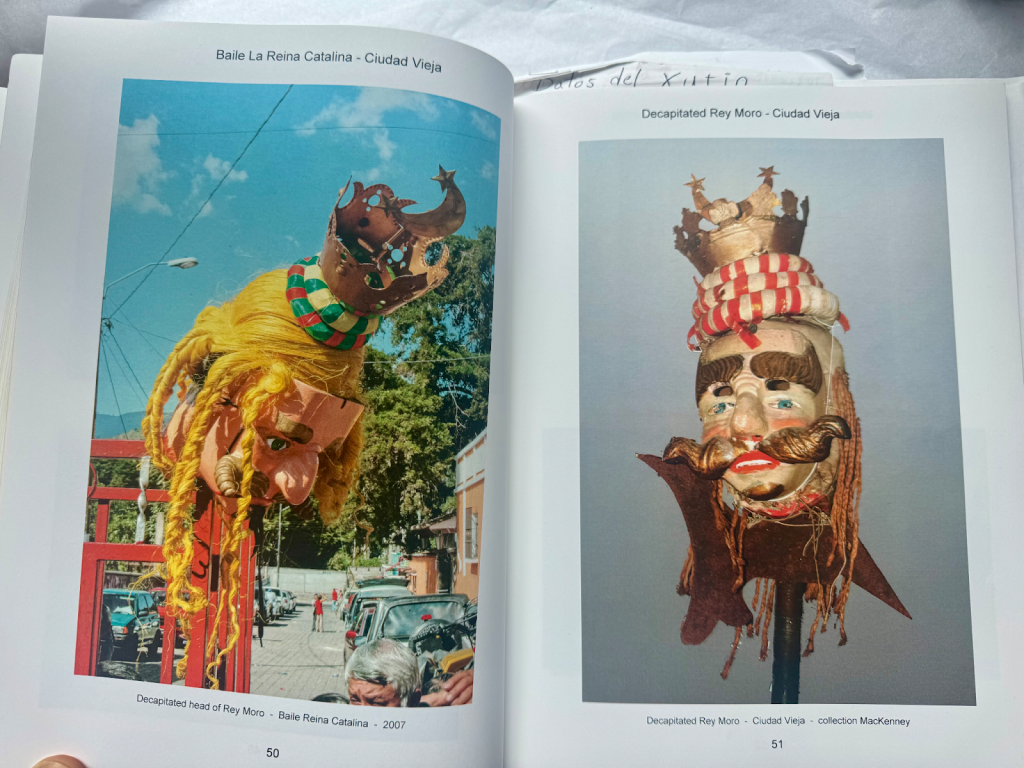

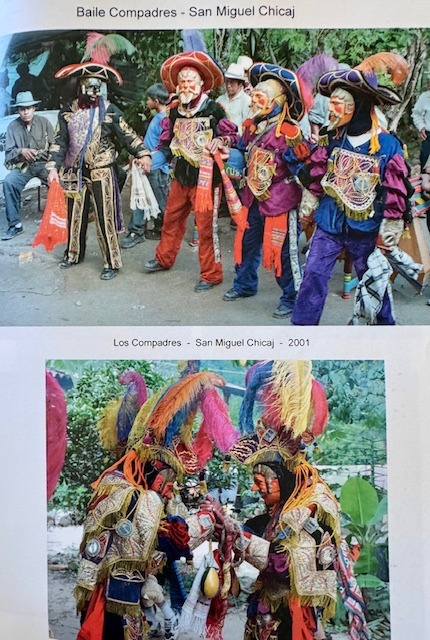

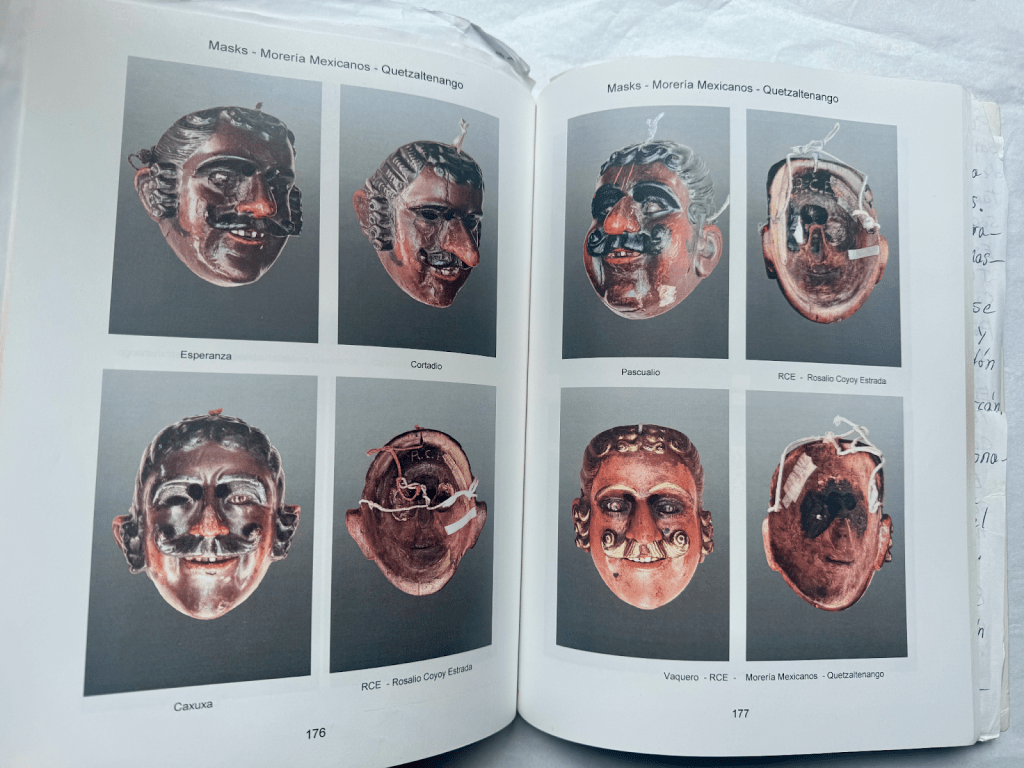

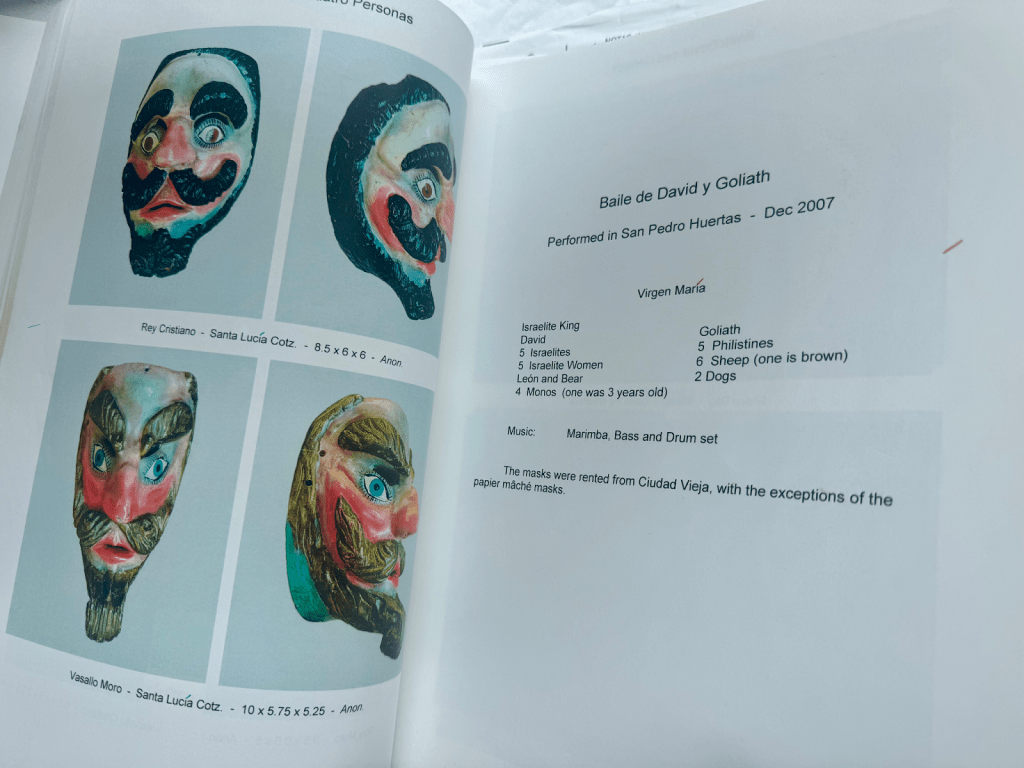

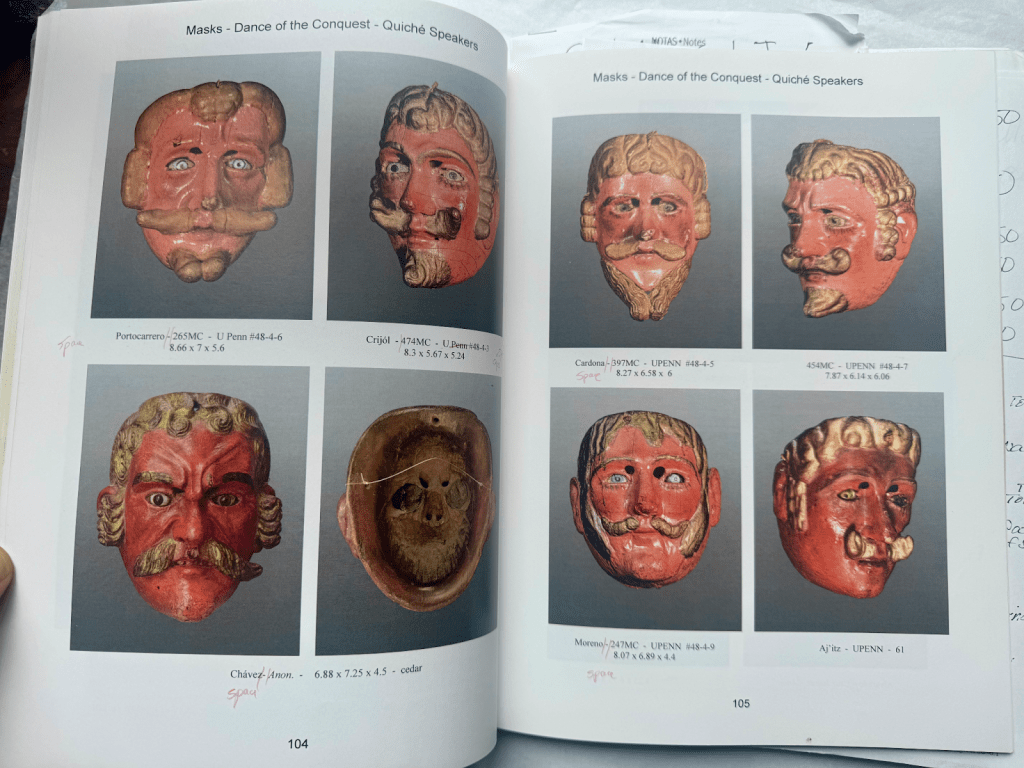

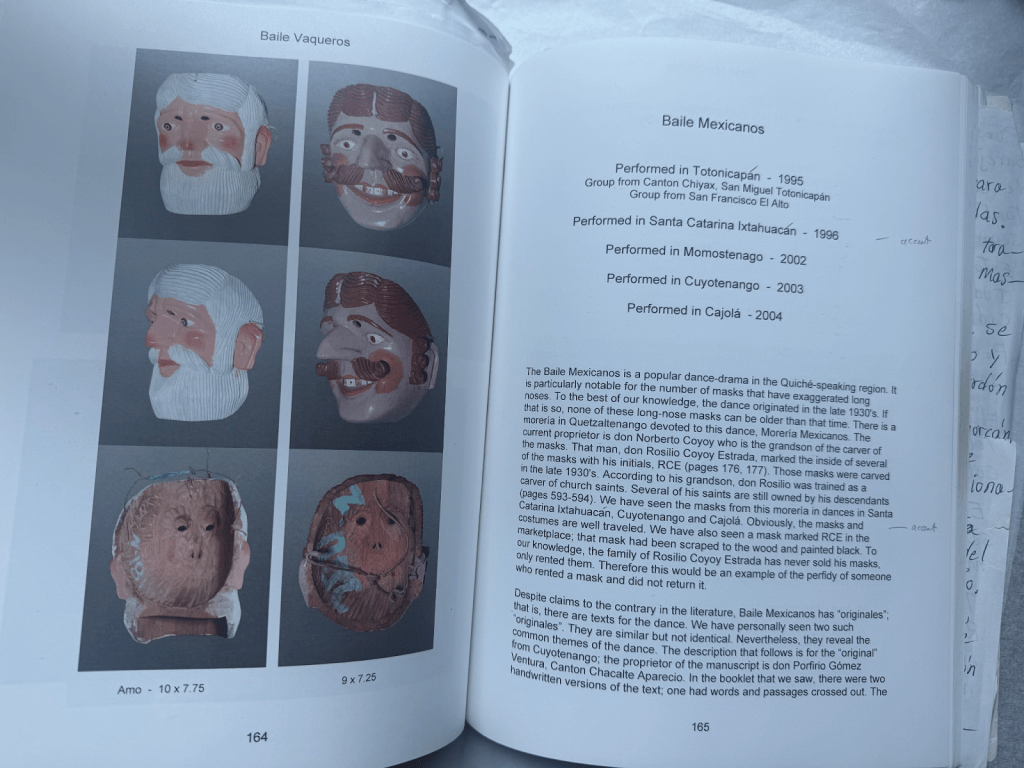

Importantly, in 2008 he co-authored along with Joel E. Bown, Masks of Guatemalan Traditional Dances, Vol 1 & 2 (2008) which is the most comprehensive book (651 pages) to date written about the dances/dramas and masks of Guatemala. The undertaking was a 15-year project and is credited with preserving Guatemalan cultural heritage whose history would otherwise have been largely lost. [FN 6]

“Masks of Guatemalan Traditional Dances, Vol 1 & 2” (Longboat Key, FL: JEB, 2008) by Joel E. Brown and Giorgio Rossilli. One online reviewer noted “This is the ultimate comprehensive survey of Guatemalan Masks ever assembled and the most accurate and serious exploration of the subject. The two-volume book examines the history, traditions and artistry behind the creation of these extraordinary objects and places them into the historical and cultural context of Guatemalan life and idiosyncrasy. The two books (Volume I and II) are a unique, high quality visual document with 651 pages of full color photographs of rare ceremonies, dance scripts, and profound investigation made over many years by Dr. Joel Brown and Gio Rossilli; both enormous connoisseurs of the subject.” [FN 7]

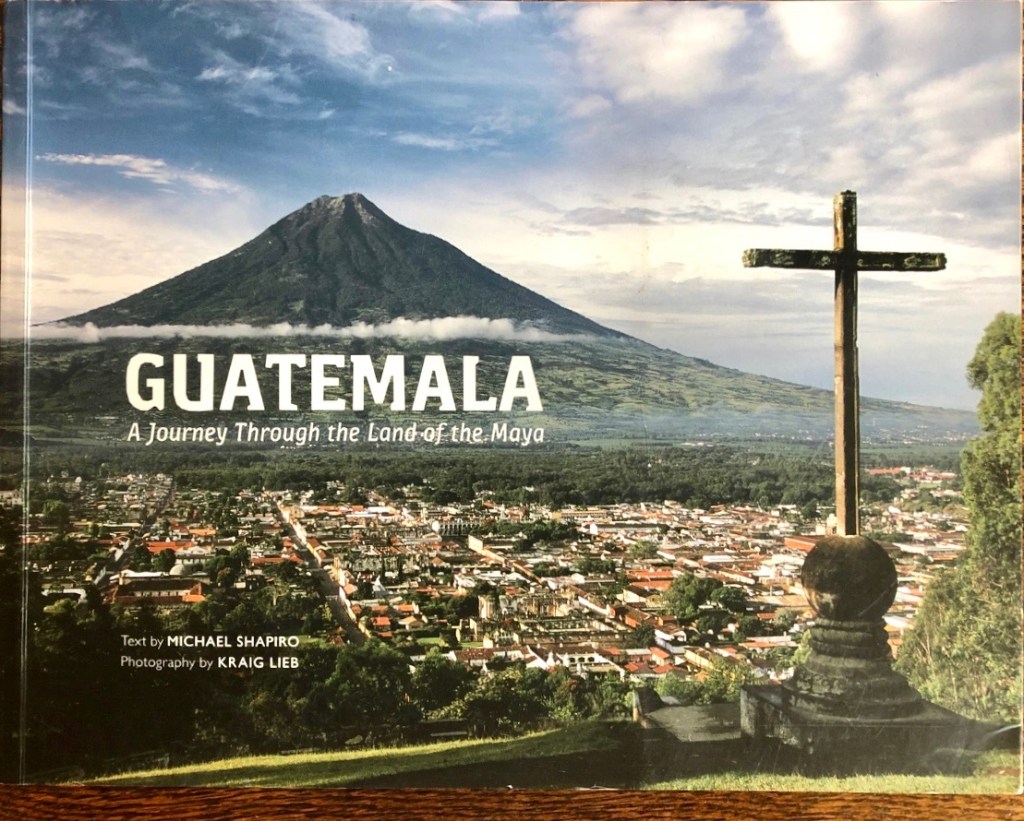

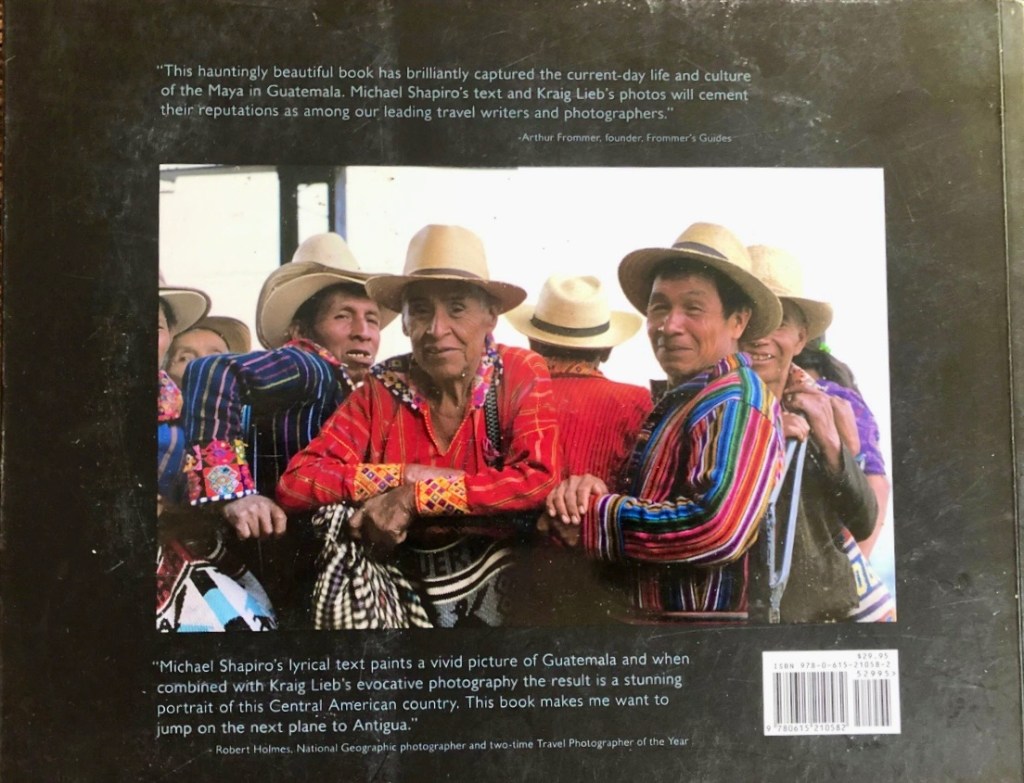

Rossilli’s other work included serving as a field guide for two contemporary ethnographic photography projects in Guatemala; one led by Kraig Lieb and the other by Thor Janson. [FN 8]

Front and back cover of Guatemala: A Journey Through the Land of the Maya (Berkeley: Purple Moon Publications, 2008), photography by Kraig Lieb and commentary and essays by Michael Shapiro.

Serving as researcher and advisor to the “The Loa Project” with Xipe Projects in California. Xipe focuses on the study and appreciation of the masked dance tradition and popular art of Latin America. Loas are morality plays (street theater of the pueblos which present good vs evil) that date back to the Spanish Colonial period and continue today. This was a 15-year project. [FN 9]

Vintage ethnographic photograph of the “Devil Dance Troupe,” courtesy of the Valey Family Estate, Santa Lucia Cotzumalguapa, Guatemala, which Rossilli helped the Xipe Foundation secure for their archive of Guatemala’s masked dance tradition.

Regarding pre-Columbian artifacts, Rossilli was the conceptual curator of “Treasures of the Maya Spirit” at the Los Angeles Art Show in 2014 which was a critically celebrated exhibition of Guatemalan Maya artifacts. The biannual publication art weekend LA noted “Treasures of the Maya Spirit focuses on the art and civilization of the Maya people and is curated by several organizations headed by Gio Rossilli.”[FN 10] Rossilli worked with La Ruta Maya Conservation Foundation (Sophia Paredes, director; Fernando Paiz, president) and Xipe Projects of Huntington Beach, CA, Friends of the Ixil Museum, and the Paiz Foundation, and was tasked with organizing the exhibition (Rossilli gained experience working in the 1990s at the Santa Barbara Museum helping to stage exhibitions, building displays and walls, etc.). The participation in the LA exhibition was in keeping with his belief that these artifacts, many from the classic period of Maya civilization (250-900 AD), should be exhibited and shared to promote Guatemalan cultural heritage. Importantly, Rossilli secured 5,000 sq ft for the exhibition (at no charge) and the art show attracted over 60,000 visitors. The exhibition in LA was a major event and received grand reviews including one from the New York Times. [FN 11]

An eight-foot-long stucco Maya sculpture of a warrior with a jaguar mask (“Crouching Jaguar”) which was part of the “Treasures of the Maya Spirit” exhibit at the Los Angeles Art Show in 2014.

Rossilli has worked with American collectors and encourages them to bequeath pre-Columbian art works back to the Guatemalan people via donations to La Ruta Maya Conservation Foundation. Additionally, Rossilli has, over the years, donated a number of pre-Columbian artifacts from his own collection in Guatemala, to La Ruta Maya, demonstrating his commitment to helping build a collection which is owned by the Guatemalan people, and ensuring its preservation for generations to come.

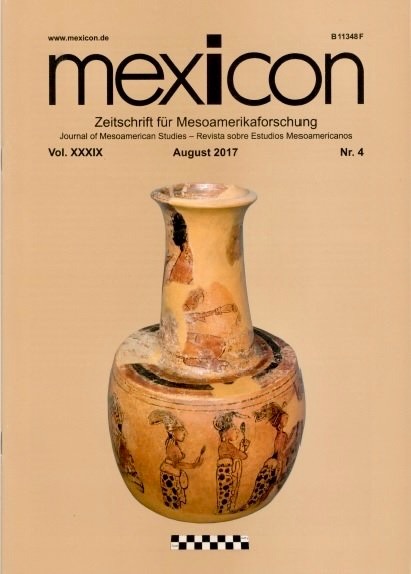

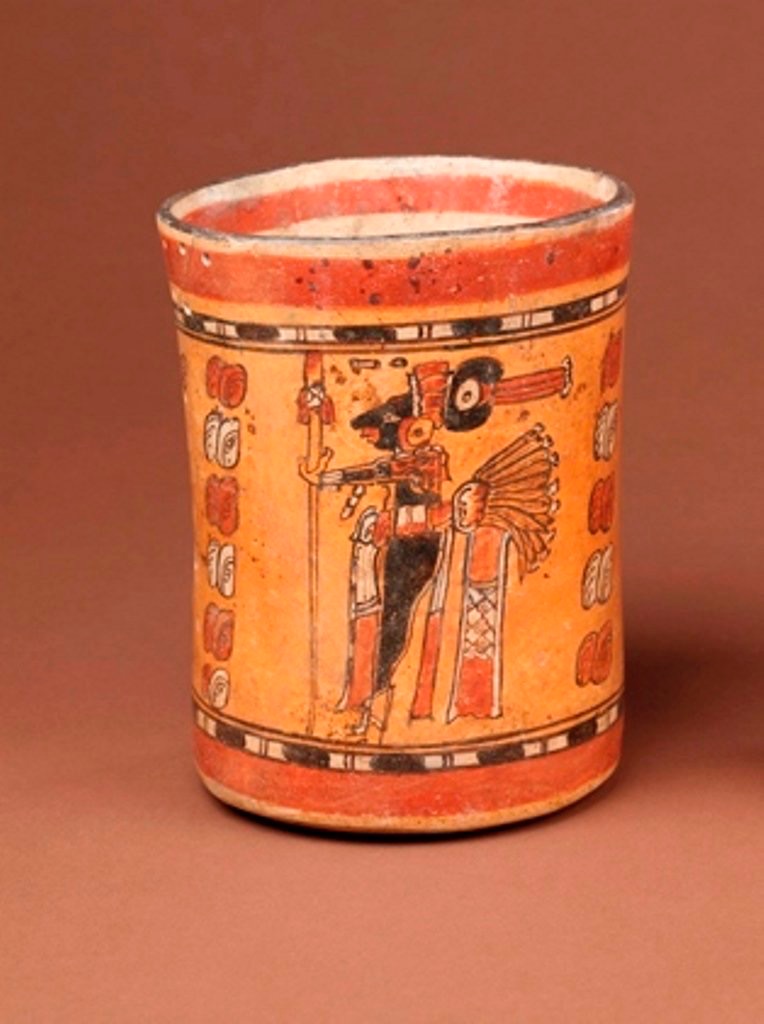

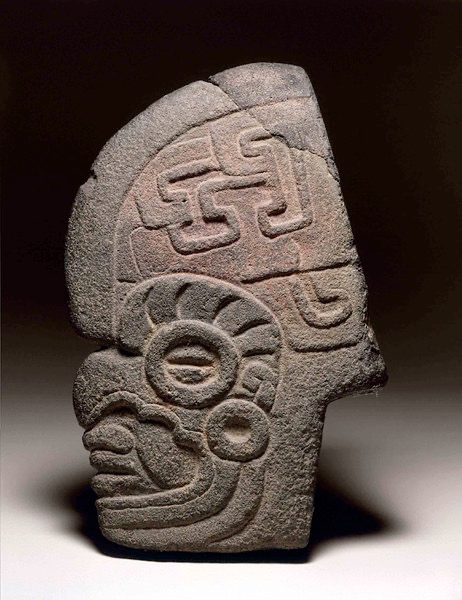

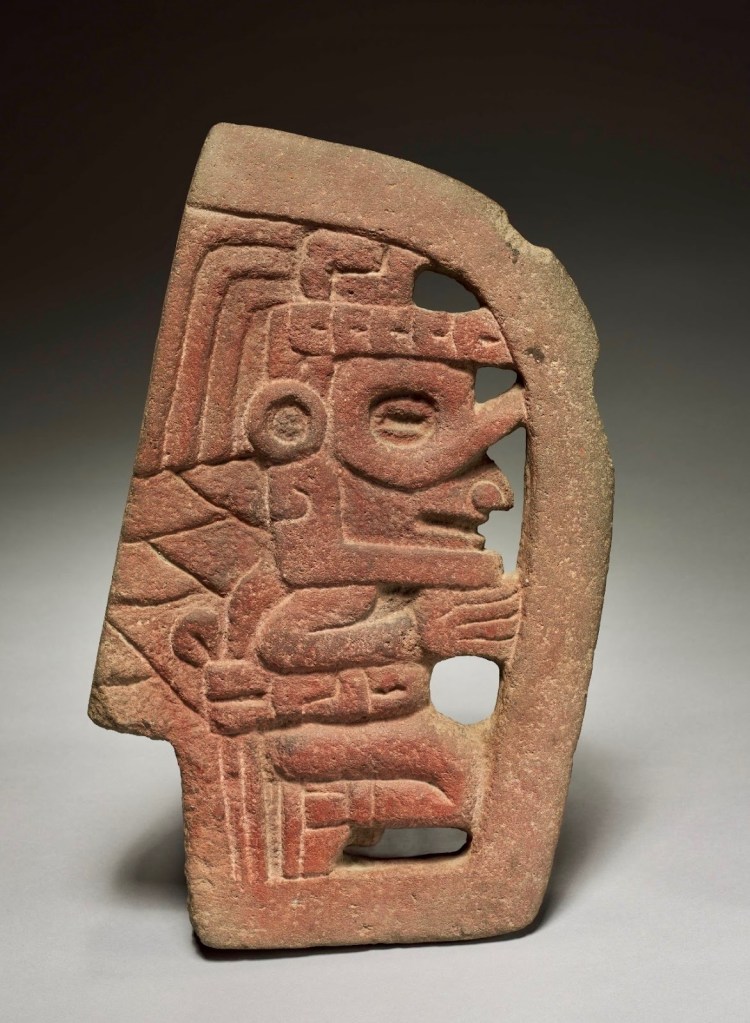

Here are examples of pre-Columbian Maya artifacts Rossilli previously donated to La Ruta Maya Conservation Foundation, including a polychrome hand drum which was depicted on the cover of the German magazine, Mexicon, in 2017; an incensario from Tiquisate; a Chama chocolate vessel; and, a stone stelae depicting the death god in the form of a skeletal monkey:

Through his 30 years of working on these projects; traveling and living among the Guatemalan people, Rossilli forged deep friendships and fostered community. Jolluck and Rossilli’s history in Guatemala counters a narrative that they would be interested in harming Guatemala or stealing its cultural heritage. On the contrary, they’ve consistently demonstrated their commitment to preserving Guatemala’s beautiful history. Yet the media and Guatemalan government never acknowledged any of this work when it rushed to publish damaging stories of the events in question.

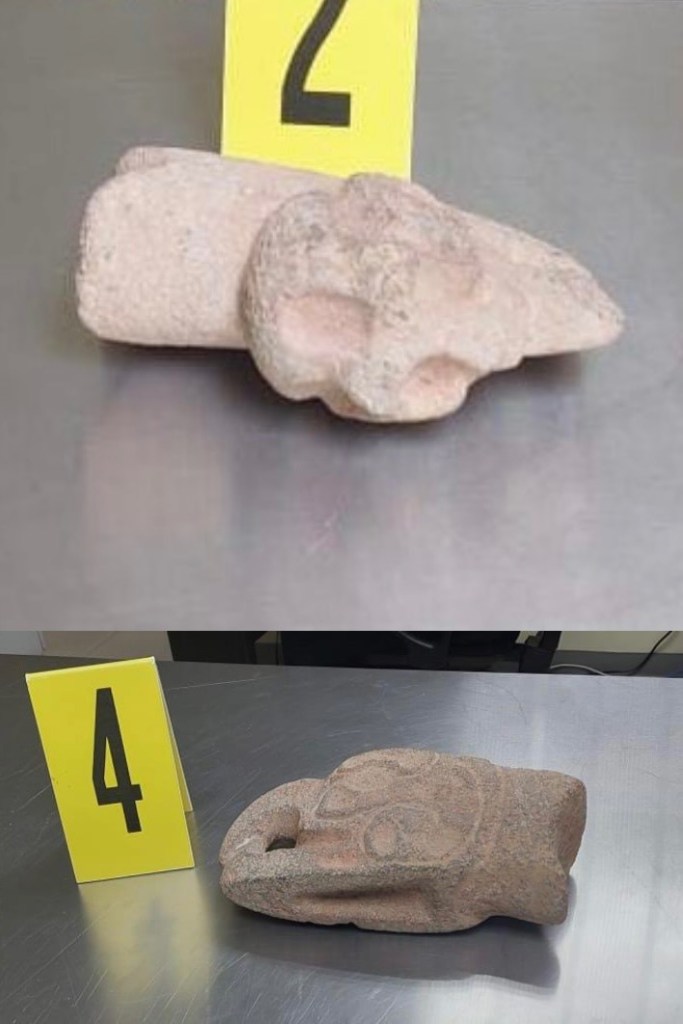

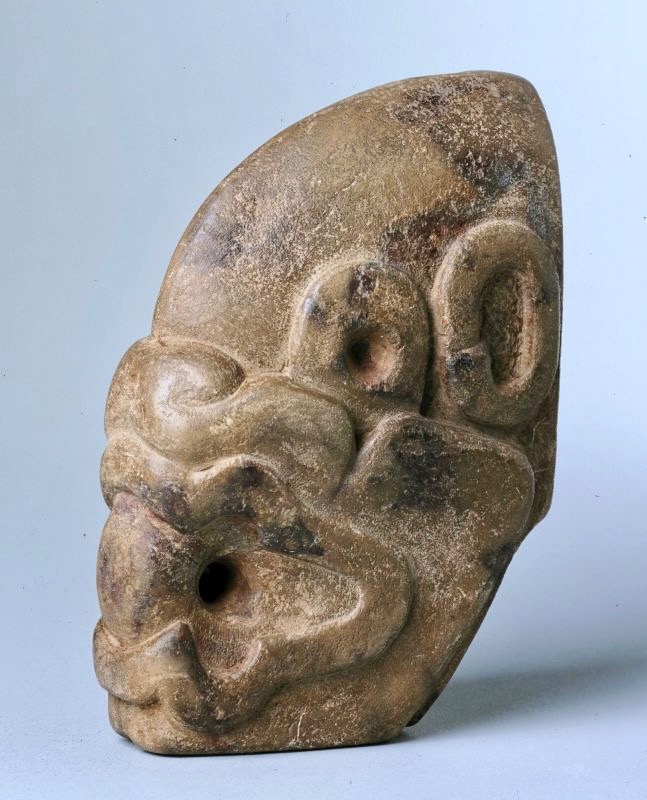

II. The precolumbian artifacts that Jolluck was arrested with are relatively minor pieces

The precolumbian stone pieces Jolluck was first arrested with, known as hachas (which is Spanish for axe) [FN 12], are completely unremarkable (even if they are determined to be real). This is primarily because they are so erosion impacted. Any collector or curator knowledgeable about precolumbian artifacts would attest to the artifacts being minor (in the sense that a museum would not likely exhibit them and collectors would not find them particularly appealing). In the collector market they would likely fetch a combined price of less than $1,000.

The two artifacts (stone hachas) that Jolluck was carrying when stopped by the Guatemalan authorities.

Many readers will ask, how could this be true? Despite the sentiment that any pre-Columbian artifact is priceless and museum worthy, the truth is that there are hundreds of thousands of artifacts already in existence and many more still being discovered as previously believed pre-Columbian geographic areas extend further than previously known. Even eroded artifacts certainly have a significance, but it should not be exaggerated. Museums are overrun with fine examples of artifacts and even in the collector market, better examples of pre-Columbian artworks routinely go unsold at auction with opening bids of under $500 U.S. dollars. Catherine Sease, a prominent figure in the field of conservation, particularly known for her expertise in archaeological conservation, stated it clearly: “Many genuine artifacts are found in such a poor state of preservation that they have little or no market value.” [FN 13]

During legal proceedings, in a move that highlights the deceitful lengths the Guatemalan authorities were willing to pursue, the government argued the individual hachas each had a value of $60,000 U.S. dollars. Again, unbiased experts with knowledge of pre-Columbian artifacts have quickly dismissed such a claim. One expert I spoke to, with over three decades experience handling pre-Columbian material, and who has helped build museum collections, gave a pointed assessment of the value of the larger and better preserved hacha that authorities confiscated. After reviewing photographs of the hacha in question, when told it was valued by Guatemalan authorities at $60,000 immediately responded “No way!,” and “That’s bullshit, you know that.” His assessment: “it could be worth $500.” Later he said, “maybe $600.” A second expert stated that the hachas were “not worth a lot to a high-end collector.” The latter avoided assigning a value. However, both immediately declined when I asked if they would legally buy the hachas for $100 each, if given the opportunity. [FN 14]

Both experts believed the artifacts to be authentic (but could not conclusively say so, given the difficulty in determining the age of stone artifacts) but also opined they mostly have an ornamental value to collectors. They are the sort of artifacts someone might place outside in a garden or backyard setting.

In addition to non-experts being unaware of the availability of these types of antiquities, many also are unaware that, under certain conditions, they can be legally bought and sold if they entered the U.S. prior to 1971 (under The UNESCO 1970 Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property) [FN 15]. As a result, there are numerous auction records to guide assessing commercial value. Even very elaborate hachas don’t sell for the kinds of numbers non-experts might expect. [FN 16]

Here is a small sampling of hachas from various museums and auctions [FN 17]:

Offered at auction in the U.S. on 7/13/22. It sold for $1,300.

One of the reasons the question mark about authenticity is continually raised is because it is very difficult, if not impossible, to ascertain the authenticity of stone pre-Columbian artifacts (as both experts I spoke to noted). Unlike ceramic pieces that are subject to thermoluminescence testing, determining the age of clay when it was fired, there is no comparable test for stone, although x-ray fluorescence analysis can determine the elemental composition of materials and is typically used for specific types of metal authentication. Radiocarbon dating can establish a timeline based on the decay of carbon-14 isotopes in cases where there is organic material. With stone artifact authentication, at best, one might be able to see tool marks in stone that were completed with modern tools but that is impossible with pieces as eroded as the ones Jolluck was arrested with.

Other types of testing really only add information around the periphery of the main question. Traditional x-ray testing can reveal repairs and the use of non-clay or stone in restoration. Also, geological dating has advanced to determine the age of some stone but cannot tell us when the stone was carved. Authenticating stone pre-Columbian artifacts still remains largely elusive. [FN 18] Howard Nowes, a leading specialist (for over 30 years) in classical antiquities, pre-Columbian, and tribal art, who also consults on conservation issues, said it succinctly: “Stone – VERY PROBLEMATIC – as to date, the dating of stone through scientific analysis is problematic because we can test the geological age of the stone but not date the objects manufacture.” [FN 19]

Moreover, it is very common for modern fakes to be sold as tourist curios or folk pieces in the markets of Guatemala. (See “Faking pre-Columbian artifacts,” by Catherine Sease, Objects Specialty Group Postprints, Vol. 14, The American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works, 2007.) [FN 20] All of this substantiates that Jolluck’s statement that she believed the pieces were not genuine, is in fact, reasonable.

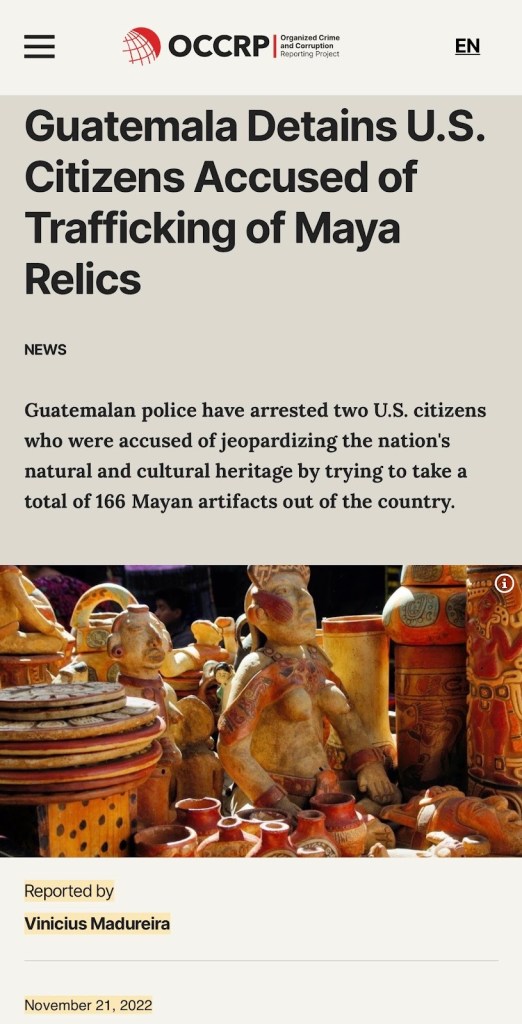

In fact, in one of the more ironic parts of this story, at least one news outlet used a photographic image to accompany their story of what, at first glance, appeared to be particularly stunning pre-Columbian artifacts (which should not have been used because the photo had nothing to do with Jolluck and Rossilli’s case), but which when examined carefully, actually depicted fakes. The image (which this news site believed depicted real pre-Columbian artifacts) was used to sensationalize the arrests and raises further questions about journalistic accuracy which has plagued this entire matter since its inception. It also makes the point that when it comes to pre-Columbian material, knowing what is real or fake isn’t always so easy to ascertain. Other news outlets used photographs of actual genuine artifacts to accompany their stories, but ones unrelated to the case, and which were far superior in quality than any of the ones pertaining to Jolluck and Rossilli’s arrest. [FN 21]

III. The Guatemalan authorities routinely confiscate artifacts in similar situations, without resorting to imprisonment and press releases

All of this brings us to the conclusion that the media reports and government ignored: the confiscation of these artifacts was completely unremarkable and should not have resulted in anything more than confiscation. Jolluck was stopped in the airport heading to Georgia to visit family. The artifacts Jolluck had were not hidden or concealed. She carried them in her carry-on bags fully expecting they would be seen while passing through security. Airport personnel were initially unsure if the objects were authentic or not. Jolluck told airport security that she believed them to be modern copies manipulated to look old. Security officials admitted it was hard to tell. Initially Jolluck was given assurances that she wouldn’t even miss her flight. What started as a delay in deciding whether to allow her to take the items with her turned into a matter of confiscation and later arrest.

Photographs from Guatemala’s various markets, including at Chichicastenango, showing how prevalent fake or replica pre-Columbian pieces are; it would not be hyperbole to say these craft objects are ubiquitous throughout the country.

Prosecutors who initially prepared the complaint against Jolluck did not allege that she was trafficking prohibited items for commercial gain. It was obvious she was not and further investigation never turned up any such evidence. Everyone seemed to be moving in a direction that would have allowed the matter to be treated summarily with a small fine and the confiscation of the objects. However, things quickly escalated with the charges amended to allege a more serious crime that carries more serious consequences, albeit at the discretion of prosecutors. The relevant criminal statute is found under the “Law for the Protection of the Cultural Heritage of the Nation,” Chapter X, Articles 43-56. Article 45 “Unlawful export of cultural assets” which states possible punishment, “Whoever exports an object of the Cultural Heritage of the Nation unlawfully shall be punished with prison sentences ranging from six to fifteen years plus a fine equivalent to twice the value of the cultural asset, which will be seized. The monetary value of the cultural asset will be determined by the Cultural and Natural Heritage Bureau.” [FN 22]

Despite these heavier charges, the statute only applies if the pieces are in fact proven to be authentic, which, as noted earlier, is impossible to ascertain with these kinds of stone objects. As archeologist and conservator Catherine Sease has noted “A wide variety of techniques have been utilized to make modern artifacts look old, including adding dirt and all manner of accretions to make the surface look worn and old.” [FN 23] This naturally only complicates any formal inquiry. Importantly, there is wide prosecutorial discretion in handling these matters, particularly in situations such as Jolluck’s arrest because it is so common that artifacts are seized from tourists as they are leaving the country; many stating they purchased the artifacts at local flea markets (where modern fakes are widely sold) and/or assumed they were not genuine. The resulting outcome typically turns on the severity of the transgression: assessing the rarity of the object and its monetary value. [FN 24]

It is common for prosecutors to treat a first offense, such as Jolluck’s, lightly. While it is against the law to take any pre-Columbian antiquity out of Guatemala, at the time of Jolluck’s arrest, it was customary for authorities to confiscate an item being impermissibly removed from the jurisdiction and issue a fine of some sort, usually equal to the monetary value of the artifacts. A second offense, depending on the circumstances, would be treated more severely, with a fine of a few thousand dollars. In neither a first or second offense would the matter result in a jail sentence if it involved one or two objects of questionable authenticity and value. [FN 25] Importantly, Jolluck had never had any problem with legal authorities in the over two decades she had spent in Guatemala.

As noted above, the artifacts in this case do not have substantial monetary value in the commercial marketplace of pre-Columbian artifacts. They are also fairly common examples, with superior ones already collected by museums in Guatemala and Mexico, thus making such examples redundant at best. In Jolluck’s case, authorities should have exercised their discretion by confiscating the items and issuing a related minor fine.

IV. The current Attorney General of Guatemala has no credibility and should not have been given a media mouthpiece to promote her agenda

The Guatemalan Attorney General’s Office took an unprecedented interest in Jolluck’s and Rossilli’s case, interceding to join local prosecutors in pursuing these matters. None of the media accounts raised concerns about this despite the recognized problems with her office.

Maria Consuelo Porras, 2018.

Guatemala’s current Attorney General Maria Consuelo Porras, who has been in office since 2018, has been deemed by the U.S. State Department as “undemocratic and corrupt.” The State Department has criticized her for undermining corruption investigations initiated by her predecessors and special prosecutors (not directly under her control) and the European Union, Canada, and the United Kingdom have all sanctioned her for her participation in anti-democratic activity. She has been criticized for persistent efforts to overthrow the 2023 national election and has been widely criticized for abusing her office to harass journalists and independent judges, in some cases specifically initiating knowingly-false criminal proceedings against them. [FN 26]

In 2024 the Associated Press’s Sonia Perez D. noted that “Guatemala’s Attorney General Consuelo Porras has been criticized and sanctioned by countries around the world for allegedly obstructing corruption investigations and using her power to persecute political opponents.” The article noted the power that she has stating that “Porras controls Guatemala’s criminal investigative and prosecutorial powers.” [FN 27]

National Security News (NSN) based in London & Washington, D.C. named Porras as the “recipient of the 2023 Person of the Year award for Organized Crime and Corruption, from the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP). This honor, far from a celebration of her achievements, emphasizes the dangerous impact of bureaucratic corruption on national security and democratic stability.” [FN 28]

Juanita Goebertus, Americas director at Human Rights Watch noted, “Attorney General Porras, who led an effort to unlawfully overturn the elections, is abusing the powers of her office to prosecute government officials through dubious evidence and legal maneuvers.” and “Instead of investigating the organized crime and widespread corruption in Guatemala, the attorney general appears to be bringing these selective prosecutions to undermine a government she opposes.” [FN 29]

The Attorney General’s adherence to the fair administration of laws is particularly significant when they have wide discretion to decide when to enforce laws and what sentence to seek. In Guatemala, two laws applicable here are in conflict, which causes confusion. All Pre-Columbian material is owned by the Guatemalan State and is considered National Patrimony. The law allows individuals or non-profit foundations to have a collection in their personal custody. Such a collection is not owned, it is simply held as a depository of the National Patrimony. The law requires all collectors to register their pieces with the Ministry of Culture, but the penalty for not doing so is a fine, and a mandatory (forced) registration. It does not allow the authorities to seize any unregistered collection. Separately, there is a prohibition from transporting pre-Columbian artifacts or moving them even within the country without prior notification and written consent. So even taking a piece somewhere for an appraisal or for advice about conservation can be deemed illegal. This obvious contradiction, since the possession of an artifact in someone’s home is circumstantial evidence that it was taken there at some time, gives Porras’ office wide discretion and is open to abuse.

After Jolluck was released pending the resolution of her arrest and subsequent criminal matter, the authorities followed her closely. Two days later they arrested her while she accompanied Rossilli who was taking artifacts from their home to the home of a well-known and respected local architect, Franklin Contreras, who owned the items. (Contreras and other family members later signed affidavits to that effect). Rossilli had been appraising the artifacts and advising on possible conservation needs. As explained above, Guatemala has no prohibition on collecting artifacts and the requirement to legally register such objects is not penalized by seizure (the remedy authorities typically implement when they discover unregistered artifacts is to require registration). However, because Rossilli and Jolluck were moving artifacts within Guatemala, even though it was less than a mile from their home, the Attorney General prosecuted them for the offense and, illegally, proceeded to seize items. The use of a statute prohibiting the transportation of artifacts, rarely used because of its inherently contradictory nature with laws allowing possession of those items, underscores a reason why there is little confidence in the fair administration of justice in this case.

Just to be clear: There is no credible claim being made by Guatemalan authorities that the artifacts Rossilli attempted to return to their owner were being taken out of the country.

Porras’s well-known disdain for due process undermined all the proceedings against Jolluck and Rossilli starting with the mischaracterization of their arrests and exaggeration of the offenses alleged to have occurred.

One of the hallmarks of the Rule of Law is that similarly situated persons be treated equally under the law; this is a foundational concept of fairness known as Equality Before the Law, which emphasizes that a society should be governed by clear, stable, and publicly known laws rather than arbitrary decisions.

V. Behind the government claims about Jolluck and Rossilli is a struggle between La Ruta Maya Conservation Foundation and the Ministry of Culture and Sports

The truth of this story is more complicated and reveals a much larger web of intrigue between the Guatemalan government (The Ministry of Culture and Sports) and an independent foundation (La Ruta Maya Conservation Foundation) devoted to the conservation and repatriation of cultural artifacts. On the one side is the government which wants all cultural heritage returned to the country, and on the other, a foundation which is led by Guatemalan citizens, who use the promise of documenting and exhibiting artifacts, both in and outside of Guatemala, as a major enticement urging collectors to donate works to the foundation. While both groups want important artifacts returned to Guatemala, the government’s desire to control the process has sparked conflict. The work of La Ruta Maya has been described by Alison Heney, Vice President of Learning and Public Programs at the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach, CA:

“Founded on October 25, 1990 by Wilbur Garrett, retired editor of the National Geographic Magazine, La Ruta Maya Conservation Foundation is organized as a nonprofit in the United States under the laws of the State of Virginia. In Guatemala, it operates a fully owned subsidiary, Fundación La Ruta Maya, registered as a nonprofit with the Ministry of Interior.

“Fundación La Ruta Maya (Guatemala) is the only private organization in Central America that promotes and manages the recovery of archaeological property that left the country illegally in the past decades, with the purpose of repatriation to Guatemala. Its vision is to foster a society concerned with the rescue and conservation of its cultural values by educating the new generations to preserve them in a sustainable manner and its mission is to recover, preserve, study and exhibit its archaeological collections, support museums, publish academic documents, and implement educational programs.” [FN 30]

Gio Rossilli and Fernando Paiz, president of La Ruta Maya Conservation Foundation, at the Los Angeles Art Show’s exhibition “Treasures of the Maya Spirit.”

Regrettably, the Guatemalan government saw Jolluck’s possible transgression as a way to undermine the work of La Ruta Maya, which Jolluck’s long time partner Rossilli has played an important role in helping to expand, as an independent curator working in conjunction with them. It appears that the Guatemalan authorities purposely sensationalized the matter in the press to undermine La Ruta Maya and cast doubt on its legitimate work. Jolluck and Rossilli’s arrests were a pretext for the Ministry’s argument that La Ruta Maya could not be trusted and justified its attempt to seize its collection, starting by cancelling its registration files.

The president of La Ruta Maya, Fernando Paiz, has long been credited for his important work. A graduate from Northeastern University in Industrial Engineering and the Masters program in Management from the Sloan School at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Paiz was recognized by the French government who awarded him the title of Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters for his efforts to protect Mayan patrimony in Guatemala. Despite this, he has now twice been prosecuted by Guatemalan authorities for the situation that arose from Jolluck and Rossilli’s case. Both times, even within the corrupt labyrinthian Guatemalan legal system, judges have dismissed each case because the government could not advance any credible theory or evidence to support their allegations. [FN 31]

The conflict between La Ruta Maya and Felipe Aguilar, who was Minister of Culture when Jolluck was arrested, is hard to explain because it is so illogical. On the one hand La Ruta Maya, which carefully maintains a collection of over 6,000 artifacts, is committed to preserving and promoting Guatemala’s rich pre-Columbian history. The Ministry of Culture also wants this, but they are reluctant, in most cases, to have any artifacts leave the country. The Ministry seems to be irritated that they do not directly control every pre-Columbian artifact in Guatemala. The National Museum of Archeology and Ethnography of Guatemalan (Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnografía de Guatemala, MUNAG) maintains a collection of over 75,000 artifacts. Rather than celebrate La Ruta Maya’s success, the Ministry sees competition.

In a prescient article from 2014, when interviewed by the New York Times, Fernando Paiz spoke about his plans to build a new museum in Guatemala that would be “the leading institution in the conservation of the cultural heritage of Guatemala.” Paiz shared that the “most difficult part may be persuading the museum of archeology and ethnography in Guatemala to support a new institution that will unify the government’s Maya collections.” Even then, Paiz was aware of the competitive attitude the government had toward La Ruta Maya Conservation Foundation’s broader vision. The New York Times noted how unusual it was for such a magnificent exhibition (the LA Art Show in 2014) to be mounted at a design show in a convention center, when it would be better situated in a major international museum. The reason is because La Ruta Maya, unlike the national museum, is devoted to exhibiting these important artifacts, even outside of Guatemala, all of which has given rise to conflicting visions of how best to honor and preserve these remarkable cultural artifacts. [FN 32]

Since 2024, the current Minister of Culture and Sports of Guatemala is Liwy Grazioso, who is part of Guatemalan President Bernardo Arévalo’s cabinet. She is a highly competent and legitimate scholar in the field of pre-Columbian antiquities. She received degrees in Archaeology at the National School of Anthropology and History (ENAH) Mexico, and a Masters in Mesoamerican Studies by the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Her areas of research interest include Mesoamerican Archaeology and the protection and conservation of cultural heritage. Grazioso was not the minister of Culture when Jolluck and Rossilli were arrested but can now play a role in correcting this miscarriage of justice. Grazioso can put a stop to the Government’s support for the heavy-handed approach to Jolluck and Rossilli’s case by acknowledging the true value of the artifacts in question and pushing to have them treated as anyone else in similar circumstances.

The La Ruta Maya Conservation Foundation plays a critical part in how cultural heritage is responsibly shared (via international exhibitions) and how repatriation works. The Guatemalan government should not be threatened by their work; rather they should celebrate how they protect its national patrimony and help to facilitate the return of significant artifacts, thus, forging ways to work in concert.

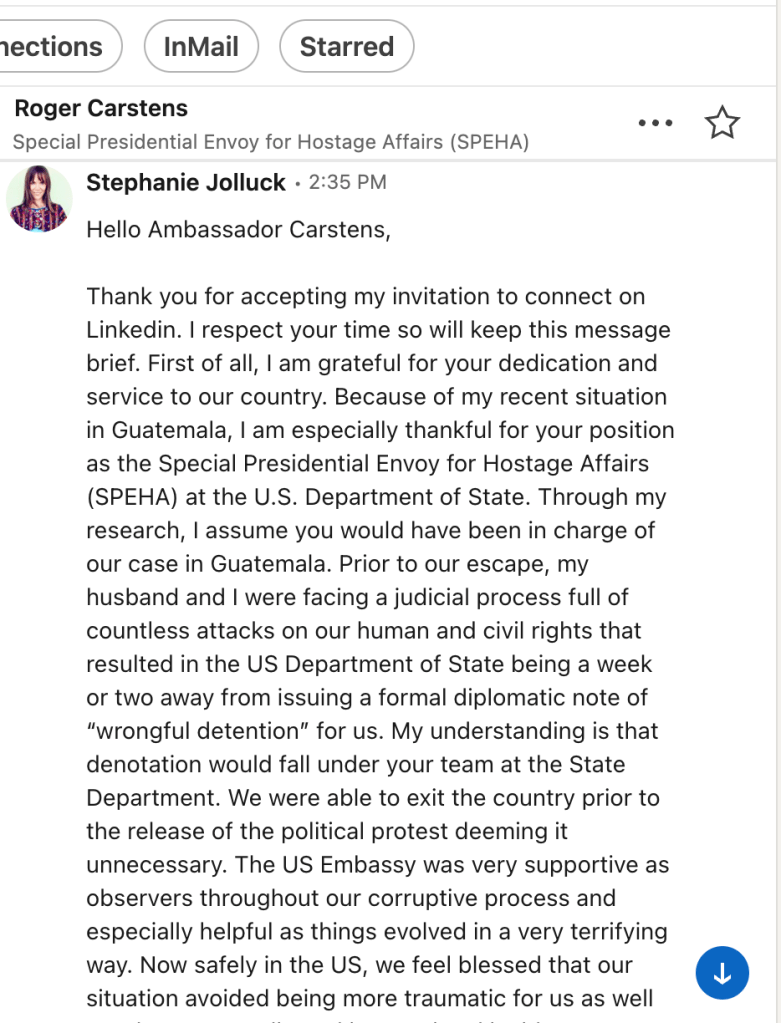

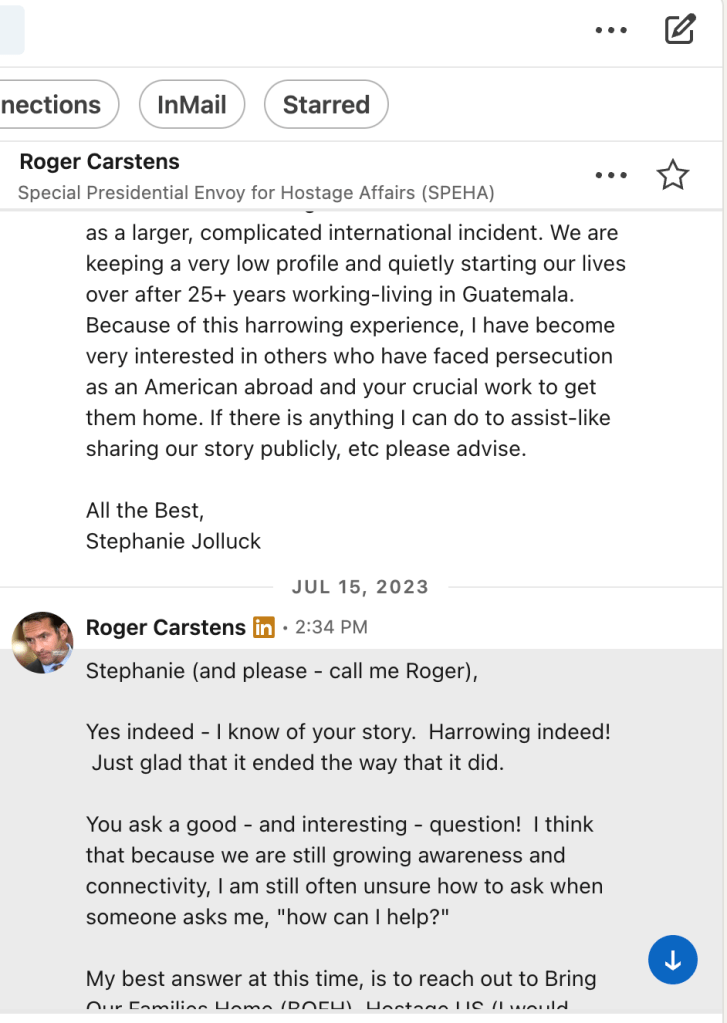

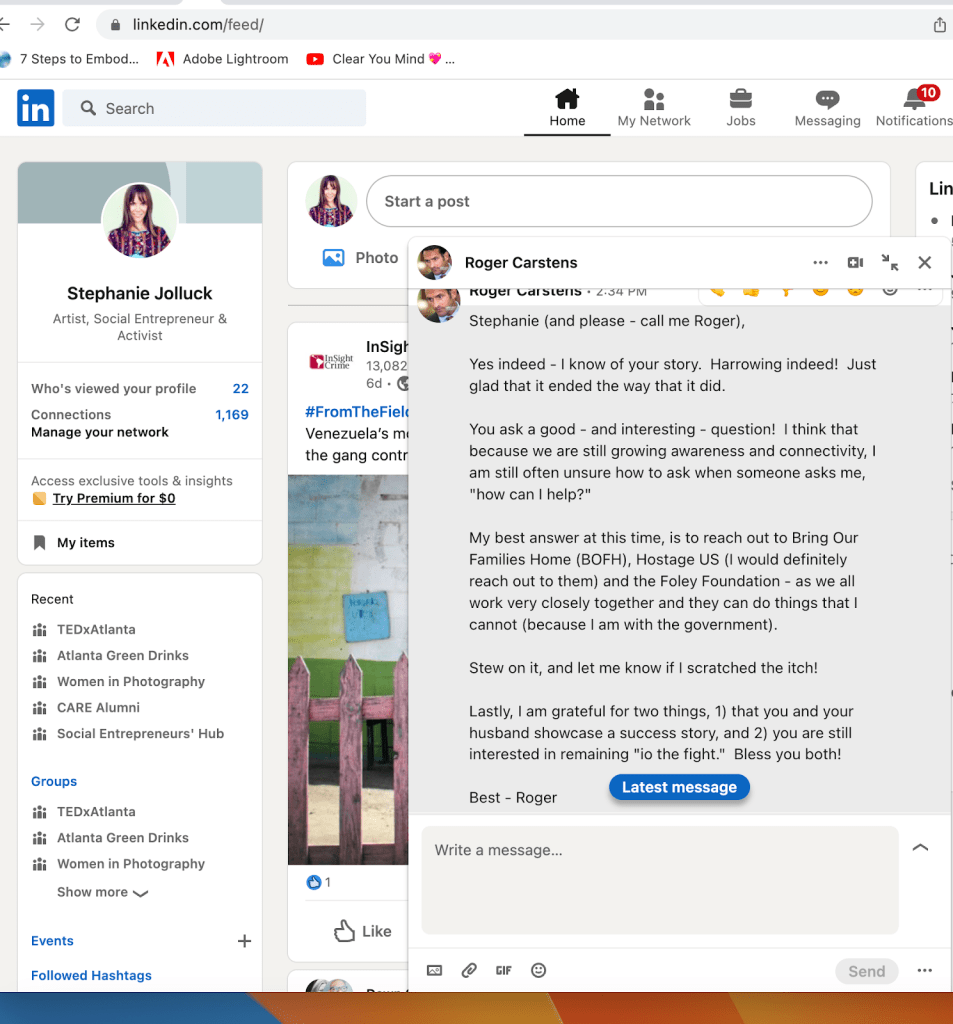

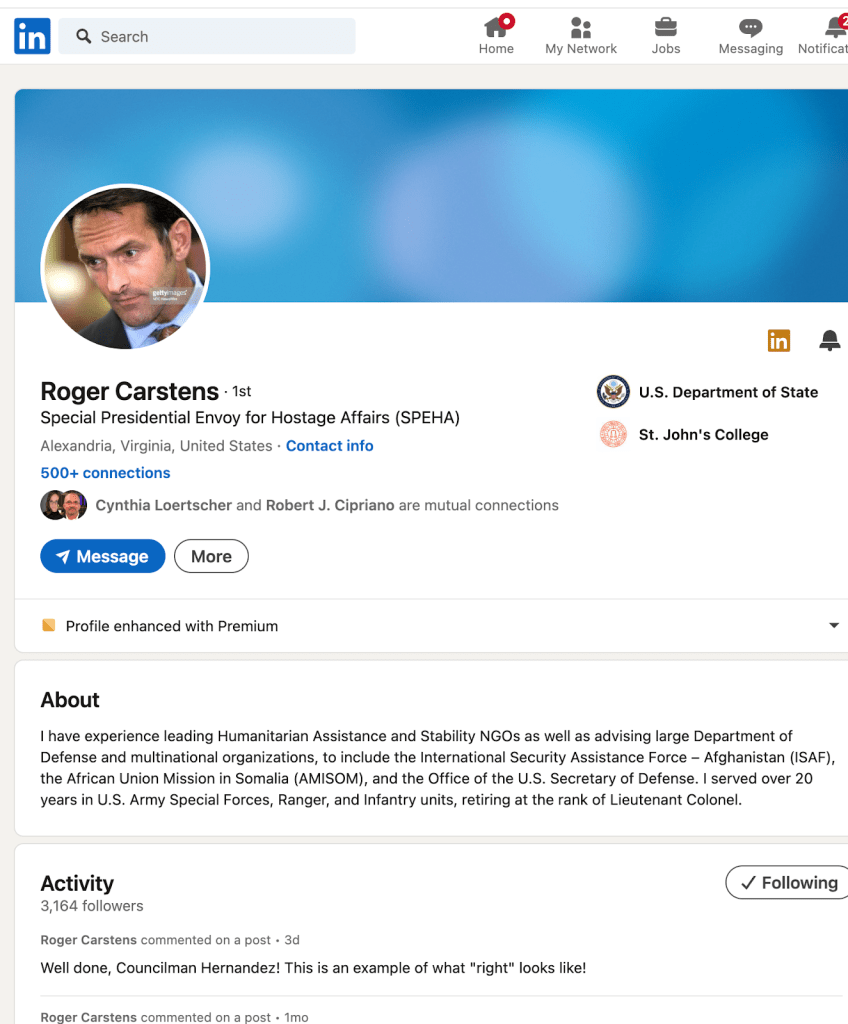

VI. The U.S. State Department finally intervened to help rescue Jolluck and Rossilli from what was obviously an unfair judicial process

Roger Carstens, the Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs in the State Department, 2020-2025.

After their arrest in November 2022, Jolluck notified the U.S. Embassy in Guatemala, and they arranged to have lawyers from the embassy attend court hearings. Although the attorneys saw a number of legal and procedural irregularities, American officials told Jolluck and Rossilli they did not feel they could intervene at that point. However, that changed on March 10, 2023 when a previously agreed upon postponement of a court hearing was ignored and the judge and prosecutors proceeded to address substantive issues in the absence of Jolluck and Rossilli’s attorneys, who had expressly relied on the court’s assurances that their presence was not needed. The absence of defense counsel was significant because prosecutors sought an extension of the investigative deadline which was to expire that very day. The court granted this request without any opportunity for the defense to raise objections.

The court should not have granted this extension. For many months the prosecution was in possession of Jolluck and Rossilli’s home and business computer and file cabinets, and had access to all of their correspondence, invoices, and financial records. They had had time to search for evidence that supported their allegations that Jolluck and Rossilli were trafficking objects out of the country and, importantly, could not find anything. To the legal observers from the U.S. Embassy and others acquainted with basic rules of law, it was apparent Guatemala was not going to afford Jolluck and Rossilli with basic due process. It is highly improper for a judge to take any substantive action in the absence of counsel for any of the parties involved. Ex-parte actions by a court and prosecutor, which exclude the defense, undermine the integrity of the administrative process and undermine fairness and impartiality. Most legal systems, including Guatemala’s which is based on civil law (derived from Spanish legal principles), strictly prohibit ex-parte actions to ensure due process of law. [FN 33] Furthermore, at the March 10th hearing, the judge proceeded despite the absence of interpreters for Jolluck and Rossilli, which is yet another breach of Guatemalan law which requires interpreters for nonnative speakers.

The legal irregularities confirmed what everyone had suspected from the outset, judicial and prosecutorial authorities were treating Jolluck and Rossilli’s case very differently. In addition to delaying the public admission that their case was weak, the further extension of time to “investigate” also gave prosecutors more time to seek to remand Jolluck and Rossilli into custody, something they continuously sought to do.

After observing how Guatemalan judicial authorities were undermining any hopes Jolluck and Rossilli had of receiving a fair trial, the U.S. State Department communicated to Jolluck and Rossilli through the Embassy that they were prepared to serve the Government of Guatemala with a formal complaint, in the form of a diplomatic note, raising objections to how Jolluck and Rossilli’s case was being handled and stating that they believed Jolluck and Rossilli were being wrongfully detained. The State Department stated that it would be better if Jolluck & Rossilli were not in Guatemala when they issued the diplomatic note because they expected retribution from the Guatemalan government. Although they made it clear they were not telling Jolluck and Rossilli to break the law, they reiterated that they believed official criticism of the government could result in the expulsion of some American diplomats from Guatemala and very likely a return to custody for Jolluck and Rossilli.

Once it was determined that it was dangerous for Jolluck and Rossilli to remain in Guatemala and participate further in Guatemalan legal process the U.S. Embassy issued emergency passports (as replacement for “lost” passports they fully knew had been surrendered to the Guatemalan court). The State Department wanted to avoid the diplomatic complaint and thus encouraged Jolluck and Rossilli’s departure from Guatemala. After Jolluck & Rossilli returned to the United States, Roger Carstens (the Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs in the State Department, who served under both Presidents Trump and Biden) communicated with Jolluck via email stating he was aware of their case, and American authorities were grateful both Jolluck & Rossilli had been able to get out of Guatemala. He called theirs one of the success stories his office monitored. [FN 34]

CONCLUSION

Jolluck and Rossilli with Manuela Gaurchaj from Nahualá.

No media outlet resisted the narrative, which the Guatemalan government controlled, once the avalanche of reporting began in this matter. Good journalism would have seen through the politically motivated attacks Jolluck and Rossili have endured. For their part, the Guatemalan government should admit that Jolluck’s and Rossilli’s case is not what they have claimed. Jolluck should have been given the benefit of the doubt, or at the least, treated as anyone else would have been. The entire case against Rossilli should be dismissed. Thus, any artifacts confiscated, which were at Rossilli’s home and which had been promised to La Ruta Maya Conservation Foundation as a donation, should be transferred to the Foundation’s collection.

Although unlikely to make amends, the Guatemalan government should acknowledge the tremendous contributions Jolluck and Rossilli have made to enhance Guatemala’s cultural heritage and recognize that they have set an example for how Guatemalan’s can honor, protect, and share their beautiful cultural history.

Jolluck and Rossilli have dealt with the aftermath of this entire matter the best they can. Obviously, they want Guatemalan authorities to relinquish their personal property which was improperly confiscated. Both continue to work and consult in areas of their expertise. Jolluck has for the last two years volunteered (20+ hours a week) at The Food Pantry in San Francisco, one of San Francisco’s largest and oldest food banks, where she is now a co-Director. She manages the donations, specifically arranging family and unhoused client’s weekly food distribution, social media accounts, and the pantry’s website. Notably, Jolluck assists many indigenous persons from Guatemala and other parts of Central America living in San Francisco, and receives satisfaction that in some measure, she can continue to help a community from her adoptive home. [FN 35]

Jolluck and Rossilli remain hopeful that Guatemalan authorities will someday allow them to return to the country and reestablish their many personal and community ties. If there is any justice in Guatemala, they will someday get their wish.

–Matt Gonzalez is the Chief Attorney of the San Francisco Public Defender’s Office. He is a former president of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. An avid collector, Gonzalez’s art collection comprises over 500 artworks. In 2020, Gonzalez donated 33 pre-Columbian artifacts to the Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA. He has also donated artworks to the Cantor Museum, Stanford University, CA; Mexican Museum, San Francisco, CA; Oakland Museum, Oakland, CA; and the Art Museum of South Texas, Corpus Christi, TX. He is the author of Art Writings: 2008–2024 (San Francisco: FMSBW, 2025).

FOOTNOTES

FN 1

Jolluck supported CARE in a variety of ways. Through her ethical fashion brand, Coleccion Luna, Jolluck donated over $25,000 in cash and products to CARE. Her brand’s handcrafted Guatemalan handbags were used by CARE at major events in Washington, D.C. (for instance, her bags were gifted to supporters at an event welcoming Helene Gayle as CARE’s Chief Executive). Additionally, Jolluck used her professional network to help CARE build relationships with other business leaders, effectively bridging the gap between the corporate and non-profit sectors to support global poverty-fighting initiatives.

FN 2

Jolluck was featured in the book “The Enough Moment (2010) as one of the “Upstanders”—individuals who have taken creative and significant action to combat injustice and human rights violations. Jolluck is profiled for her humanitarian efforts, specifically focusing on how personal activism can lead to sustainable change. In the context of the book, her story serves as a practical example for readers on how to combine business with social advocacy to empower marginalized groups and prevent further human rights abuses.

FN 3

Here’s an article from the Huffington Post about this peace campaign;

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/emmanuel-jal-peace_b_2046528

Jolluck with Emmanuel Jal, former President Jimmy Carter, Rosalynn Carter, and others, meeting to discuss the project We Want Peace In Sudan.

FN 4

More photographs taken by Stephanie Jolluck:

FN 5

“This is the only comprehensive survey of Guatemalan slingshots ever assembled and the first serious exploration of the subject. Up until now, this traditional handicraft has only been prized by a few collectors and the artisans themselves. However, original shapes and elaborate carvings using imagery derived from the animal kingdom, Mayan and Catholic iconography, and myths and historic events make them stand out as cultural artifacts. With this publication, this unique craft gains the importance it deserves. The Guatemalan Slingshot delves into the history, culture, and artistry behind the creation of these distinctive objects and places the slingshot into the broader historical and cultural context of Guatemalan life, describing the country s relationship to the slingshots from its agricultural beginnings, to commercial plantation and industrial production of rubber, to tourism. The book is also a lasting, high quality visual document with over 50 photographs of Guatemala and its culture and over 400 color photographs of slingshots ranging from Superman to the Virgin Mary, soldiers to guerilla fighters, Quetzales, traditional dancers, and beyond.”

Additional photographs from Las Hondas Guatemaltecas / The Guatemalan Slingshot (Antigua: La Ruta Maya Conservation Foundation, 2007) by Anabella Paiz and Valia Garzon:

FN 6

Additional photographs from Masks of Guatemalan Traditional Dances, Vol 1 & 2 (Longboat Key, FL: JEB, 2008) by Joel E. Brown and Giorgio Rossil:

FN 7

Martin Kaukas Books in Manchester, Vermont. See the listing here:

https://www.abebooks.com/servlet/BookDetailsPL?bi=32103420575

Joel Brown has described the book: “This book provides the most recent, the most comprehensive and the most accurate description and identification of masks of Guatemalan traditional dances. The book presents full color photographs of more than 330 masks, many in more than one view. These photos were taken in both public and private collections in Guatemala, the USA and elsewhere. The book also presents more than 850 full color photos of masked dancers; many of these photos show individual masks. The dances photographed include the “Dance of the Conquest of Guatemala” (from 4 regions of the country), several versions of “Moors and Christians” (“Moros y Cristianos”), the “Rabinal Achí”, “Mexicanos”, “Toritos” (the “Little Bulls”), “Diablos” and 37 other dances. These photos were taken during dance performances in many locations in the country over a period of 15 years. These photos provide the information necessary for the accurate identification of masks with specific dances and characters within those dances. That is, this information allows the accurate identification of many masks held in collections or those that appear in the marketplace. The book also shows photos of many “morería marks”; these signatures aid in the determination of provenance of the masks. In addition, the book describes the various materials from which Guatemalan masks have been made, and presents previously unpublished information about the “dramas” that the dances represent. The book will be useful to both collectors of Guatemalan masks and to those people interested in anthropological and ethnographic information about Guatemalan dance-dramas.”

FN 8

Works by Thor Janson:

https://www.librarything.com/author/jansonthor

About Kraig Lieb:

http://thingsasian.com/author/kraig-lieb

FN 9

“With sincerest thanks to Gio Rossilli of Antigua Guatemala whose efforts made all of this possible, the Tinker Foundation, and most of all, the Valey Family Estate, I am excited to announce that we are laying the foundation for what we hope will be a significant contribution to the study and preservation of this part of the Guatemalan dance tradition – The Loa Project.” –Alison Heney, PhD, Curator, December 2014.

About Xipe Projects:

http://www.xipeprojects.com/maestro-and-the-dance.html

FN 10

Review of the “Treasures of the Maya Spirit” exhibition in art weekend LA:

“Treasures of the Maya Spirit is an exhibition that celebrates Maya culture and its contributions to the world. The exhibition will present more than 200 extraordinary examples of Pre-Columbian Maya Art, and will also feature some of the finest examples of native Guatemalan textiles, antique masks, and dance costumes, as well as contemporary works of art by prize-winning artists and anonymous artist-artisans, reflecting the Maya region’s worldview.”

The exhibit included many non-pre-Columbian artifacts including this slingshot from La Ruta Maya Conservation Foundation’s collection:

FN 11

“Stalking Heritage Far From Home” by Edward Rothstein, New York Times, January 17, 2014.

FN 12

A figural hacha is typically made from stone or volcanic rock. It is generally a flat form resembling a symbolic axe. It presents as a profile with carvings often representing animal forms such as birds, monkeys, or even skulls. Some anthropologists believe they were boundary demarcations, others believe they may have had a role in the ceremonial Mesoamerican ball game. Here is a further explanation:

https://www.denverartmuseum.org/en/object/1985.395

FN 13

“Faking pre-Columbian artifacts,” by Catherine Sease, in Objects Specialty Group Postprints (a project of The American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works), Volume Fourteen, 2007, (pages: 146-160).

Catherine Sease holds degrees in anthropology from Bryn Mawr College and in archaeological conservation from the University of London. She worked as a conservator for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, was the head of conservation and collections management at the Field Museum in Chicago, and is currently the senior conservator at the Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University.

https://www.museum-sos.org/htm/res_bio_sease.html

FN 14

Neither expert wanted to be named since they had not personally examined the artifacts. Their assessments were not contingent on handling the pieces, however, neither was particularly impressed by the objects and both were certain the value the Guatemalan authorities placed on the artifacts was grossly inflated.

FN 15

The primary law for this purpose is the Law for the Protection of the Cultural Heritage of the Nation (Decree number 26-97). This law, amended by Decree No. 81-98 of 1998, aims to protect and conserve objects considered part of Guatemala’s cultural heritage and establishes penalties for actions that violate this protection, including illegal export.

FN 16

There is a vibrant debate on whether legitimate pre-Columbian items of lesser value should be allowed to be commercially traded. For our purposes it’s useful to see academic discussion noting that many artifacts have diminished value, which is something lay people unacquainted with the pre-Columbian market often don’t believe:

“Archeologists estimate that ninety percent of the objects found in digs are duplicates that have no great value. (citing Paul M. Bator, The International Trade In Art 1-2 (1983)). There is, therefore, no compelling reason why a legitimate trade in duplicates should not be allowed. The national patrimony is not threatened by the exportation of an object which is identical to many already existing in museums in the home country. By allowing a trade in such works, the black market demand for such goods is lessened and the art-rich countries are better able to protect their most important pre-Columbian works and sites from pillage. Because the scope of the enforcement is decreased, more officials will be available to police and protect the most important elements of their countries cultural heritage. Further, the revenue that can be generated from the legitimate trade can then be funneled back into excavating new sites and protecting and preserving existing artifacts and sites. (citing Alexander Stifle, Was This Statue Stolen?, National Law Journal, November 14, 1988).”

James K. Shedwill, “Is the ‘Lost Civilization’ of the Maya Lost Forever?: The U.S. and Illicit Trade in Pre-Columbian Artifacts,” California Western International Law Journal, Vol. 23, No. 1 [1992], Art. 7.]

FN 17

Additional auction records.

Arte Primitivo auction records / Howard S. Rose Gallery, NYC:

2025

$500 bid, unsold.

https://www.arteprimitivo.com/scripts/detail.asp?LOT_NUM=179412

$750

https://www.arteprimitivo.com/scripts/detail.asp?LOT_NUM=178624

$1,000

https://www.arteprimitivo.com/scripts/detail.asp?LOT_NUM=179413

$2,600

https://www.arteprimitivo.com/scripts/detail.asp?LOT_NUM=179419

2022

$5,250

https://www.arteprimitivo.com/scripts/detail.asp?LOT_NUM=168329

$8,000

https://www.arteprimitivo.com/scripts/detail.asp?LOT_NUM=168327

2021

$5,000

https://arteprimitivo.com/scripts/detail.asp?lot_num=164484

2020

$1,800

https://arteprimitivo.com/scripts/detail.asp?lot_num=162019

2018

No bids

https://www.arteprimitivo.com/scripts/detail.asp?LOT_NUM=153749

$3,250

https://www.arteprimitivo.com/scripts/detail.asp?LOT_NUM=153742

2017

$2,200

https://arteprimitivo.com/scripts/detail.asp?LOT_NUM=149621

2014

$1,150

https://www.arteprimitivo.com/scripts/detail.asp?LOT_NUM=139819

Auction records accessible from LIVEAUCTIONEERS, examples:

No bids, starting at $500

https://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/64834519_mayan-volcanic-stone-hacha-head-w-bird

Much better example sold for $500

https://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/194419376_pre-columbian-maya-stone-ball-game-hacha

$600

https://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/61533505_mayan-stone-hacha-fragment-head-of-snake

No bids, starting at $1,700

https://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/67248980_maya-stone-hacha-animal-human-effigy

Sold $2,250

Sold $750

https://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/40665427_maya-cultual-hacha

FN 18

Regarding the various testing procedures for pre-Columbian antiquities:

https://www.ciram-lab.com/en/our-services/art-market/stones-minerals

FN 19

https://howardnowes.com/blogs/news/pre-columbian-art-primer-for-appraisers

FN 20

“Faking pre-Columbian artifacts,” by Catherine Sease, in Objects Specialty Group Postprints (a project of The American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works), Volume Fourteen, 2007, (pages: 146-160).

FN 21

Below is a photograph used by Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project’s news reporting of Jolluck and Rossilli’s arrest. The artifacts depicted are obviously fake (to any expert) and do not accurately reflect the additional items found in Jolluck and Rossilli’s possession.

See the screenshot of the story below:

Here is a photograph taken by authorities showing many of the actual minor artifacts, mostly fragments, that were found in Jolluck and Rossilli’s possession:

At least one NBC affiliate used a photograph of what might be a genuine pre-Columbian artifact to lead its story, but the photo was unrelated to anything found in Jolluck or Rossilli’s possession. See the screen shot below:

One story by the French international news agency AFP actually used a photograph depicting precolumbian artifacts from Costa Rica, also unrelated to Jolluck and Rossilli’s case:

This misleading reporting, particularly suggesting artifacts of higher quality and value were involved, was disingenuous and only amplified the inaccurate information circulated about the case.

The actual photograph of many of the artifacts in Jolluck and Rossilli’s possession (above) depict fragments that are not scarce and have very little commercial value. Here is a comparable photo of over 26 pounds of fragments (yes pounds, not the number of items) that sold at auction in 2022 for a total of $550 U.S. dollars.

Leonard Auction, Addison IL, Lot 0487, June 25, 2022.

https://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/130293934

Again, every time the media reported hundreds of artifacts being found in Jolluck and Rossilli’s possession, they failed to explain that the vast majority were extremely minor. By amplifying only the number of artifacts without further explanation, they mislead their readers into believing or speculating that Jolluck and Rossilli were part of a large trafficking ring.

In Guatemala, it is not illegal to own genuine pre-Columbian artifacts (even hundreds of fragments). Sharing this information with readers is essential to responsible reporting. Unfortunately, this was often a detail absent from the news articles about Jolluck and Rossilli’s case.

FN 22

“Current law designates all of Guatemala’s archeological artifacts as government property. But collectors can sidestep legal risk because once a piece is entered into a national registry — regardless of how it was obtained — it becomes legal to have in their possession, according to a legal source who spoke to InSight Crime.” Max Radwin in “Black Market for Mayan Artifacts Still Thrives in Guatemala,” InSight Crime, February 25, 2020.

See also:

https://webhelper.brown.edu/joukowsky/resources/culturalpatrimony/2579.html

FN 23

“Faking pre-Columbian artifacts,” by Catherine Sease, in Objects Specialty Group Postprints (a project of The American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works), Volume Fourteen, 2007, (pages: 146-160).

FN 24

“Indigenous Threatened Heritage in Guatemala,” by Victor Montejo in Bandarin, Francesco, et al. Cultural Heritage and Mass Atrocities. Getty Publications, 2022. Project MUSE, https://muse.jhu.edu/book/101799.

“For example, Article 60 of the constitution reads, “Paleontological, archaeological, historical, and artistic assets and values of the country form the cultural heritage of the Nation and are under the protection of the State. Their transfer, export, or alteration, except in cases determined by the law, is prohibited.”16 One clause—“except in cases determined by the law”—is critical. Which law? And who applies it?”

https://www.getty.edu/publications/cultural-heritage-mass-atrocities/part-2/15-montejo/

FN 25

The United States and Guatemala have an agreement related to archaeological objects:

“To prevent the illegal trafficking of archaeological objects, in 1997 the United States and Guatemala created a memorandum concerning “Restrictions on the Import of Archaeological Objects from Pre-Columbian Cultures.” The United States has enforced the agreement, but the same should be demanded of each country with which Guatemala has diplomatic relations and agreements.”

US Department of State, “Guatemala (97-929)—Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Imposition of Import Restrictions on Archaeological Objects and Material from the Pre-Columbian Cultures of Guatemala,” 29 September 1997, https://www.state.gov/97-929.

From the opinion of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois – 845 F. Supp. 544 (N.D. Ill. 1993), October 14, 1993

“For the purposes of this motion, it is accepted that the law of Guatemala provides that upon export without authorization, the artifacts are confiscated in favor of the Republic of Guatemala, and become the property of Guatemala. Article 21 of Guatemala’s “Congressional Law for the Protection and Maintenance of the Monuments, Archeological, Historical, Artistic Objects and Handicrafts” provides for “confiscation in favor of the State” upon illicit export.” United States v. Pre-Columbian Artifacts, 845 F. Supp. 544 (N.D. Ill. 1993).

https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/845/544/1460032/

There are conflicting indicators of what the law in Guatemala actually is. Here it suggest the maximum prison sentence is higher and the potential fine is lower: “Guatemalan authorities step in when someone tries to remove, sell or transport one of these pieces without proper registration, a crime that could result in penalties as harsh as 15 years in prison, as well as a fine of 10,000 quetzales (about $1,300).” See Victor Montejo (above) “Indigenous Threatened Heritage in Guatemala,” by Victor Montejo citing:

I would caution against giving too much weight to maximum penalties as such potential sentences for an offense are typically not a good indicator of how the offense is generally handled by prosecutors. Even in California, for instance, a petty theft (Penal Code section 484) can be punished with a maximum of a six-month sentence in the County Jail. However, it is routine for first offenders to be given a warning or allowed to participate in a diversionary, community service, program which results in their case being dismissed.

FN 26

Maria Consuelo Porras Argueta De Porres is subject to sanctions according to Open Sanctions:

https://www.opensanctions.org/entities/Q52577583/

The UK just extended its financial sanctions against Porras until 2027.

FN 27

“Guatemala is stuck with a problematic attorney general, a legal study says,” by Sonia Perez B. (Associated Press), City News Everywhere, October 8, 2024.

FN 28

National Security News (NSN), London & Washington, D.C.:

“Maria Consuelo Porras, Guatemala’s Attorney General, emerged as an unexpected yet controversial recipient of the 2023 Person of the Year award for Organized Crime and Corruption, from the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP).

“This honour, far from a celebration of her achievements, emphasises the dangerous impact of bureaucratic corruption on national security and democratic stability.

Porras is accused of protecting a corrupt political elite involved in organised crime, drug trafficking, and widespread corruption. Porras has been implicated in obstructing justice, persecuting honest prosecutors, journalists and activists, and purging pro-democracy officials from positions of power.

“Porras is protecting what has been called in Guatemala ‘the pact of the corrupt,’ which involves bent businessmen, corrupt politicians, members of organised crime, and retired generals,” said Maria Teresa Ronderos, director of the Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística.”

FN 29

“Guatemala: Attorney General Pursues Political Prosecutions,” Human Rights Watch, December 18, 2024.

https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/12/18/guatemala-attorney-general-pursues-political-prosecutions

FN 30

Alison Heney quotation from:

https://www.alison-heney.com/la-art-show

More about La Ruta Maya Foundation

FN 31

More information about Fernand Paiz:

FN 32

Quoted in “Stalking Heritage Far From Home” by Edward Rothstein, New York Times, January 17, 2014.

FN 33

There can be exceptions, in rare instances, but they did not apply here.

Guide to Guatemalan law:

https://guides.loc.gov/law-guatemala/legal-guides

FN 34

LinkedIn messages between Jolluck and Ambassador Roger Carstens.

Carstens served as the Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs from 2020 to 2025. It provides supporting evidence that the Biden Administration’s State Department acknowledged Jolluck and Rossilli were being designated “wrongful detainees/hostages” of the Guatemalan government due to unfair judicial process

Only 1-2% of American detainees abroad are “wrongfully detained” according to the State Department. The criteria to be so designated are very strict, yet Jolluck & Rossilli met the requirement for extraordinary assistance.

Robert Levinson Hostage Recovery and Hostage-Taking Accountability Act:

https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/712

The use of diplomatic notes:

Hostage & Wrongful Detainee Criteria from the Foley Foundation:

More about Roger Carstens:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roger_D._Carstens

FN 35

The San Francisco Food Pantry:

https://www.instagram.com/thefoodpantrysfo

–THE END