first published as Let’s Bellyache! A book review in the San Francisco Call, May 24, 2002

A SLAP IN THE FACE! A book review

by Matt Gonzalez

[Suicide Circus: Selected Poems by Alexei Kruchenykh (Copenhagen & Los Angeles: Green Integer, 2001). Translated from the Russian by Jack Hirschman, Alexander Kohav, and Venyamin Tseytlin, with an Introduction by Jack Hirschman and a Preface and Notes by Guy Bennett.]

POET AND TRANSLATOR JACK HIRSCHMAN brings us the first single-volume poetry collection in English of one of the central figures of Russian Futurism. Affectionately called the “bogeyman of Russian literature,” Alexei Kruchenykh (pronounced Crew-chon-ik) didn’t so much open the door of modern poetry as kick it off its hinges and toss it to the side. Revered as a great experimenter and provocateur in his day, Kruchenykh trail-blazed the early 20th century literary frontier like some kind of Russian Magellan, charting a course into the poetry of sound. A contemporary and Futurist colleague of Vladimir Mayakovsky and Velimir Khlebnikov, Kruchenykh was hailed by Pasternak as “standing on the edge – a living fragment of art’s imaginable frontier.”

Kruchenykh was, with Khlebnikov, the leading practicioner of “zaum” poetry, that is, poetry comprised of made-up words – an idea believed to have been suggested to him by the painter David Burliuk in late 1912. Zaum, also known as transrational poetry, was meant to go beyond express intelligibility without devolving into nonsense – it was intelligible in an implied, innate way, because it relied on the roots of words and their sounds to suggest meaning in the poem. By liberating the poem from actual words which, standing alone, were perhaps less relevant to the socio-political upheavals of the time, the Futurists embarked on a radical poetics that complemented the events of the day.

Kruchenykh and his colleagues anticipated Hugo Ball’s sound poetry (klanggedicht), first performed at the Caberet Voltaire in 1916, which combined sounds whose meaning, or meaninglessness, was equal in any language. Interestingly, it is believed that the Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky read Ball some of Khlebnikov’s poetry in Zurich in 1916. If true, this places Dada’s language experiments in a direct lineage from those of the Russian Futurists. Kruchenykh’s transrational language clearly was ahead of its time – pushing the limits of understood poetics. Huddled between Cubism and Dadaism (generally said to have been launched in 1907 and 1916, respectively) the various strands of Russian Futurism made great strides toward a modernist agenda by exploring color, sound, design, and constructions.

The translation of Suicide Circus was begun by Hirschman and Alexander Kohav in 1976. Hirschman, himself a poet who has experimented with verbal-visual works and who comes out of a Russian declamatory tradition, has a familiarity with the Russian language and much in common with Kruchenykh. In addition to translating many books by Russian authors (including Mayakovsky, Andrei Voznesensky, Robert Rodzhdestvensky, and Natasha Belyaeva), he translated an essay on Kazimir Malevich which appeared in the well-known Los Angeles County Museum catalogue of the 1980 Russian Futurist show there. He is also the subject of Henry Hills’ short experimental film “Kino Da!” (4 min., 16mm, 1981) which shows Hirschman reading a poem he composed in Russian (which Hills has edited through a cut-up method to resemble a zaum poem). Like Kruchenykh, Hirschman’s books have experimented with facsimiles of his own handwriting and with hand-written one-of-a-kind works (i.e., Yod (London: Trigram Press, 1966) and Soledeth (Venice: Q Press, 1971)). Hirschman has over 100 titles to his credit, many of them self-published, and he has collaborated with many artists including Wallace Berman, Dean Stockwell, George Herms, Russel Tamblyn, and Agneta Falk. Likewise, Kruchenykh, who published 200 books during his lifetime (though he preferred to use the term “productions” when describing his works), hand-made many of them and collaborated with artists for cover designs and illustrations. In fact, the list of artists Kruchenykh worked with reads like a who’s who of the Russian avant-garde: Natalia Goncharova, Mikhail Larionov, Kazimir Malevich, Ivan Kliun, Kirill & Ilya Zdanevich, Maria Sinyakova, Igor Terentiev, and Kruchenykh’s own wife Olga Rozanova.

Hirschman’s introduction recalls fondly how he and Kohav, a dissident poet from the Soviet Union, worked on the translations at the Caffè Trieste and Vesuvio’s Café in North Beach, and how they would burst out in laughter at Kruchenykh’s many puns and word games. Subsequently, Hirschman solicited Venya Tseytlin, a young Russian poet from Moscow, to translate some of the later poems of Kruchenykh that comprise the last quarter of the book. At a March 20th reading at City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco, Tseytlin rightfully observed that Kruchenykh’s use of invented words and phrasings resembles a kind of Russian hip-hop or rap, when one considers how he crafted language.

The poem “Dir byl shchyl” is probably the best known zaum poem. Guy Bennett, who supplied the notes to Suicide Circus, goes so far as to call it the archetype zaum poem and notes that Kruchenykh enjoyed stating that it was more Russian than all of Pushkin’s poetry. Such hyperbole was common among the Futurists. The first part begins in a strictly zaum manner and is then followed by sections that fuse “sound” elements with pre-dada/surrealist tendencies which together form a new type of rationality in the poem. The following translation is by Hirschman and Kohav:

Dir bul shchyl

three poems written

in my own language

deferring from others’,

their words have no

definite meaning

1. Dir bul shchyl

ubeshshchur

skum

vy so bu

r l ez

2

Frot fron yt

I don’t argue I’m in love

black language

the wild tribe had it

too

3

Ta sa mae

kha ra bau

saem siyu oke

rainoke mola

al

The flowing moon

Now looks out

Now hides

A quarrel – shhh!

Lustra’s tearing the

stormclouds apart

that one’s dressed flowing-cloudlike

bread’s out on the table

cabbage soup

They say a nude woman’s

beautiful in the moonlight

The voice is deaf faces are red

Snacking mushrooms drinking

Spattering saliva scurrying

Ah where can I skedaddle to get away from you

The sky cleverly covering

with dove-blue grey rags

the whole night Busy with caviar

the sky’s choking and smelling of

the color of dove and udders

O love me pity

me

Eitherway I’m bleeding

me and you

Eitherway I’m already crucified

by the steppe and the willows

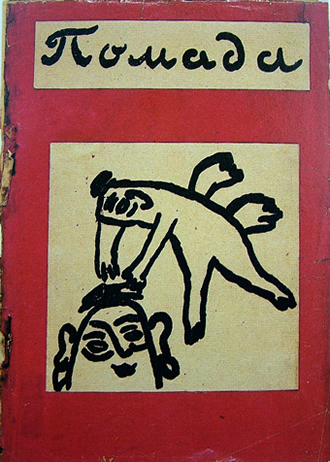

(First published in Kruchenykh’s Pomade, 1913)

Alexei Kruchenykh’s Pomade, 1913. Illustrated by Mikhail Larionov. From The British Library collection.

The year before “Dir bul shchyl” was published in Pomade, Kruchenykh, Mayakovsky, Khlebnikov, and Burliuk published the manifesto “A Slap in the Face of Public Taste.” This essay gives insight into what these young men believed they were doing. Though they themselves were criticized for being unintelligible, the Futurists struck back in kind, arguing that traditional poetics were irrelevant – and yes – unintelligible: “The past is too tight. The Academy and Pushkin are less intelligible than hieroglyphics. Throw Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, etc., etc. overboard from the Ship of Modernity.” Specifically, they stated their intention “[t]o enlarge the scope of the poet’s vocabulary with arbitrary and derivative words (Word-novelty).” Mayakovsky, in particular, later underscored the relevance of placing Futurist poetics within the context of the modern city: “The poetry of Futurism is the poetry of the city, of the contemporary city – Feverishness is what characterizes the tempo of the contemporary world. In the city there are no flowing, measured lines of curvature: angles, fractures, zig-zags are what make up the profile of the city.”

In his introduction to Roman Jakobson’s memoir, My Futurist Years, Stephen Rudy notes that the Futurists generally worked to free language in the poem from referentiality, preferring to focus on the form of the composition in much the way Cubism focused on the medium itself. Kruchenykh said as much himself in a 1913 essay: “Futurist painters like to use parts of the body, cross-sections; futurist poets use chopped words, half-words, and their whimsical, intricate combinations.” This approach is evident in poems such as “Dir bul shchyl.” By distorting language through the infusion of unfinished words, or sounds and roots of words, and by promoting the fragment, the Futurists challenged the normal way language was understood. Sound and understanding, or sense, was essentially recast. The resulting product was at times so estranged from normal language that words and phrasings lost their common or habitual meanings and created a new sensation out of the collective fragments of sounds. The reconfiguration of language then is what Kruchenykh was pursuing. It was not nonsense, but rather a different sense created out of the same base habitual language comes out of. Zaum, which means literally “beyond sense,” disrupted traditional grammar and became nothing less than the vehicle for the pursuit of a new language and hence a new poetics.

Actress Julia Solntseva, producer Alexander Dovzhenko, and Futurist poet Alexei Kruchenykh, 1930. Photograph by Aleksandr Rodchenko.

The Green Integer imprint, of Sun & Moon books, is illustrated with reproductions of the various ephemeral book covers published in early editions of Kruchenykh’s work. These illustrations make apparent how Kruchenykh’s works were first presented and the full nature of his experimentation. The series itself is impressive. It includes hard-to-find and never-before-published shorter works in English translation by such writers as Garcia Lorca, Huidobro, Celine, and Gellu Naum. Although small in size (6 x 4 in.), each packs a punch. Publisher Douglas Messerli deserves credit for launching this series.

Reading Kruchenykh today, one is struck by how his legacy differs from that of other “avant-garde-ists.” As a general matter, it can be said that avant-garde movements don’t age well. That is to say, with the passing of years, once these movements have been canonized, it is often hard to conjure up what was so radical about them in the first place. The photomontage work of John Heartfield or the abstract canvases of Franz Kline are good examples. Each dramatically changed our culture and yet today one can hardly look at a magazine without seeing commercialized examples of each. But Kruchenykh’s work is different. He was “so out there” that the label of ordinariness or normalcy never attaches to his work. And this will likely remain true as we approach the centennial of his first zaum experiments.

Kruchenykh is relevant to a 21st-century audience because his spirit reached back to the primitive, though he hid his efforts in the discourse of modernity. He has been called Futurist, Neocubist, pre-Dadaist, but ultimately his language experiments and the appeal to sound within his poems were about how to find the base of what language is, and in that manner they were no less about examining what it is to be human and what it means to communicate in a society. If Kruchenykh’s poetry is sometimes crude, it can be said that he made up for it in daring. Whoever explores this volume will see that he fulfilled the spirit of the avant-garde many times over. Nevertheless, Kruchenykh himself cautioned against a diet of only the zaum: “Transrational poetry is a good thing, but it’s like mustard – one’s appetite can’t be satisfied with mustard alone.”

This small volume will usher in a new appraisal of Kruchenykh’s work. Who can say what impact the Russian Futurist really made? Mayakovsky’s remark about how the group got its name could just as easily speak to their legacy: “It was the newspapers that gave us the name ‘Futurists.’ Anyway, why get all worked up. It’s funny! If Vavila had shouted: ‘Why am I not Eugene?’ what difference would it make?”

References

The Avant-garde in Russia, 1910-1930. Ed. Stephanie Barron & Maurice Tuchman. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1980.

Burliuk, David, Alexey Kruchenykh, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and Velimir Khlebnikov. “Slap in the Face of Public Taste,” 1912, in Russian Futurism Through Its Manifestos, 1912-1918. Trans. Anna Lawton & Herbert Eagle, ed. Anna Lawton. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1988.

Gurianova, Nina. Exploring Color: Olga Rozanova and the Early Russian Avant-garde, 1910-1918. Trans. Charles Rougle. Amsterdam: G+B Arts International, 2000).

Jakobson, Roman. My Futurist Years. Trans. Stephen Rudy & ed. Bengt Jangfeldt. NY: Marsilio, 1992.

Janecek, Gerald. “Zaum” & “Futurism.” In Dictionary of the Avant-gardes, by Richard Kostelanetz. Chicago: a cappella books, 1993.

Khlebnikov, Velimir. Collected Works, Vol. 1: Letters and Theoretical Writings. Trans. Paul Schmidt & ed. Charlotte Douglas. Cambridge and London: Harvard University, 1987.

Markov, Vladimir. Russian Futurism: A History. Berkeley & London: Univ. of California Press, 1968.

Mayakovsky, Vladimir. Listen! Early Poems, 1913-1918. Trans & intro. Maria Enzensberger. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1991.

Rabochiye, chto chitat’ vam? [What Should You Read, Workers?], a poster by Alexei Levin (1893-1968) with versed text by Vladimir Mayakovsky (1892-1930). Published by [Moskovsky Rabochy], Moscow, 1924. 104.5 x 70.5 cm.

I have been thinking for a while that I must read some Kruchenykh.

Grreat post thankyou