first published in As It Ought To Be, December 21, 2011

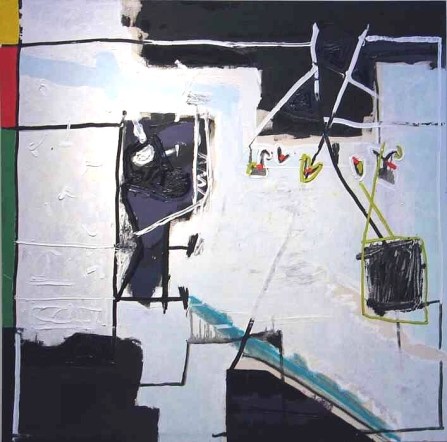

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Sin titulo, oil on canvas, 48″ x 48″, 2011.

GUSTAVO RAMOS RIVERA AT ELINS/EAGLES-SMITH

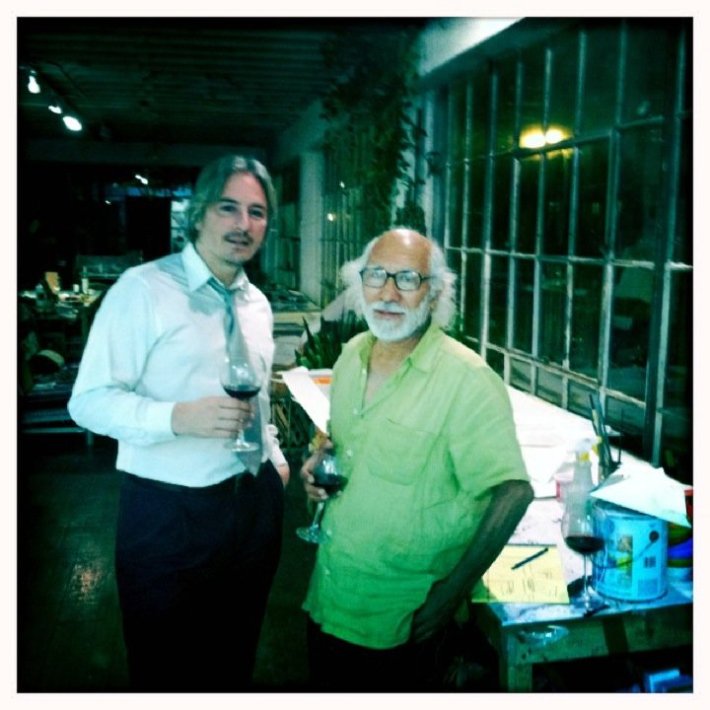

by Matt Gonzalez

Since the early 1900s when Xavier Martinez settled in San Francisco, there have been many Mexican-born artists working in the region. Today the list includes Enrique Chagoya, Jet Martinez, Calixto Robles, Juvenal Acosta, and Gustavo Ramos Rivera. Rivera (known as Ramos Rivera in Spanish) has been working in San Francisco the longest — over four decades — and is internationally known.

A native of Ciudad Acuña, Coahuila, Rivera has shown in many Bay Area venues, including Charles Campbell Gallery, John Berggruen, Smith Andersen Editions, Hackett-Freedman, and the San Jose Institute of Contemporary Art.

His second solo show at Elins/Eagles-Smith, “Gustavo Ramos Rivera: Paintings and Works on Paper,” runs through Saturday, Dec. 31. The show features eight large paintings, one a diptych measuring 7 by 7 feet, and a number of gum prints (a form of monotype) made while working at Atelier Tom Blaess in Bern, Switzerland, earlier this year.

Most art critics have noted Rivera’s Mexican or Latin American palette and place him in a lineage of painters whose work tries to approximate the Mexican landscape, meaning, it is dominated with bright primary colors, particularly reds and yellows. But Rivera’s abstract work also belongs to a tradition of Bay Area painting among artists such as John Grillo, Richard Diebenkorn and Frank Lobdell, all of whom adhered to formal elements in the work and whose use of color emphasized subtle contrasts.

The paintings at Elin/Eagles-Smith are composed over areas of compartmentalized color fields, with spontaneous brushwork and palette knife application that relies heavily on under-painting seeping through the top-coat of paint. It is coupled with a wandering line of paint as if Rivera is drawing with it, rendered straight out of the tube or with the pointed back end of a brush. This drawing work doesn’t seem confident or premeditated, rather it recalls the Surrealist efforts at automatic writing. In many places the resulting canvas looks as if Rivera is just scribbling, reminiscent of child’s play, suggesting further connections to the accident and scramble so critical in Dada and Surrealist aesthetics.

Nevertheless, Rivera’s finished canvases reveal a formalism that indicates a mature artist who both juxtaposes and combines intention with spontaneity.

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Portal de Luz, oil on canvas, 60″ x 60″, 2005.

Rivera outlines forms on the canvas with black or other colors. The results are hardly recognizable. Sometimes you can see part of a cross, a wheel with spokes, a crescent moon shape on its side, or a desolate tree. But these symbols, which some have called a “personal hieroglyphics,” are so obliterated by the process of abstraction that the work can just as easily stand as non-objective. Yet some kind of landscape is strongly suggested in these works and the partial signage Rivera uses offers a glimpse into his subconscious.

The finished paintings look as if Joan Miró, Mark Rothko, and Cy Twombly collaboratively painted over Richard Diebenkorn’s Ocean Park series, with Rothko or Twombly taking turns with the final pass.

Installation photograph of Bulerías and Sin titulo at Elins/Eagles-Smith Gallery by Alan Bamberger, November 3, 2011.

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, detail of Bulerías, oil on canvas, 84″ x 85″, 2009.

The most impressive painting in the show is the diptych that measures 7 by 7 feet, titled Bulerías, which refers to the well-known rapid flamenco rhythm. Rivera sustains the composition despite a central vertical line separating the two canvases. The painting is comprised of separated color fields joined with lines and the collision of vibrant primary colors over black under-painting. Although non-objective, the work suggests the patterns of a dance movement or even a contraption of some kind, fully equipped with mechanized levers and extension cords.

It is worth noting that Rivera’s art-making of the 1960s was in a more traditional, figurative style of painting that depicted the human condition, in the manner of Jose Luis Cuevas and Francisco de Goya. Later, Rivera passed through a period where his palette was often darker, and merged his figurative work with abstraction. During this time he was preoccupied with texture and color experimentation. In those mid-career works, landscape emerged as a predominant element in the painting.

The work at Elins/Eagles-Smith features elements of obliterated symbols which hint at the earlier, transitionary period of Rivera’s work, where the fragmentary language now present took a more direct and recognizable form. These transitional paintings feature figurative elements and signage that directly reflect the landscape of Rivera’s birthplace. They include representations of the sun and moon, trees, festival banners, rivers, church steeples, crickets and dirt paths. These forms are often combined with a visionary poetic context, made up of dark and brooding images that emphasize the mythologist in him. Comparisons to the Surrealist work of Manolo Millares, Joan Ponç and Modest Cuixart, of the post-World War II Catalonia group, the Dau al Set, come to mind.

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Arrecife, oil on canvas mounted on wood, 48″ x 48″, 2011.

In time, Rivera evolved into full abstraction in the tradition of Antoni Tàpies, also a founding member of the Dau al Set. Gestural, eschewing figuration, yet retaining formal elements in the work. These are the paintings on exhibit at Elins/Eagles-Smith.

By burying nearly indecipherable signs throughout the work, Rivera unconsciously references events and places in his life which ultimately withstand the artist’s turn to abstraction. The explicit figurative element have disappeared, but shapes remain: crosses, trees, and organic forms such as one might find in a Miró.

Like the Russian Futurist who believed zaum poetry had meaning because it used syllables of words to suggest them, Rivera is implying meaning through the obliteration of the image. Or like Franz Kline, who used a Bell-Opticon in the late 1940s to magnify drawings and thus understand how a part of a drawing could stand alone as a painting, Rivera’s painting gives little hint of its origin.

Regrettably, the current show does not include any of Rivera’s wood sculpture, which the gallery previously exhibited in 2009, and Ben Bamsey has referred to as “abstract totem poles.” Made from discarded wood scraps, tree limbs, broom handles, and milk cartons, they are fastened with nails and wire and painted in bright colors and sometimes even equipped with wheels.

But otherwise this is a perfect show.

As a boy Rivera fondly recalls being asked to paint a chair. His father presented him with brush and paint and let him go. There he discovered a love of covering something in paint. The walls of the family home became his next canvas. This current show presents decades of what is at its root a childish impulse to play. But it also conveys the artist’s very personal and individual relationship to the world. Rivera succeeds every time because he is pure of mind as he faces off with the canvas. He isn’t trying to paint something any more than he did when he painted his first chair. The painting is all self-expression.

Matt Gonzalez and Gustavo Ramos Rivera, August 17, 2011. Photographs by Tony Hall.

More images of artwork by Gustavo Ramos Rivera: