original to The Matt Gonzalez Reader, November 5, 2016 (updated 05/22/23)

One of eight known versions of Paul Wonner’s Still Life with “Femme au Coq.”

Paul Wonner and the “Femme au Coq” paintings of the 1950s

By Matt Gonzalez

During the 1950s, Paul Wonner returned to a subject matter in his art making practice, the painting of a still life with femme au coq, translated from the French as woman with rooster. Anyone familiar with modern European painting would recognize the motif, as it was explored by many artists, including Pablo Picasso and Marc Chagall. The trope presents the rooster as a symbol of sexuality, virility, and fertility. Paired with the woman, it exalts romantic love and the heterosexual coupling traditionally associated with marriage.

It is curious that Wonner would find the subject matter interesting enough to return to it during the mid-1950s, at least eight documented times, while he was a student at U.C. Berkeley. Of course painters often return to the same landscape or paint a subjects’ portrait repeatedly, but the painting of a subject that is so allegorical and laden with symbolism is not as common. It suggests Wonner was intrigued by or wrestling with its meaning in connection with his own life and art.

In his depiction of the femme au coq narrative, Wonner diverges at a critical moment. He upends the story line as if he isn’t actually in accord with the central theme of this traditional motif. His women, in nearly each of the paintings for which we have an image, look frightened and disturbed. They lack any of the softer facial expressions that accompany the Picasso and Chagall versions. Wonner may initially have chosen to address the subject matter in part as an homage to the European masters he sought to emulate. However, the notable interpretive shift in tone suggests he infused the scene with his own biography, in effect, a commentary on society’s expectations toward heterosexuality.

In Marc Chagall’s versions, the rooster is often placed in a scene with a couple. There is no ambiguity that it’s a festive affair. He renders the lovers as tender and sweet, exalting romantic love.

Marc Chagall, Étude pour Le coq vert ou La Femme Oiseau (Study for The Green Rooster or The Bird Woman) 1949 & Marc Chagall, The Rooster, 1929.

In Pablo Picasso’s much reproduced 1938 oil painting, “Femme au Coq,” the rooster sits in the lap of a woman. While the scene isn’t as romantic as those depicted by Chagall, it is still playful, portraying man as captive to, or threatened by, an adoring women.

Pablo Picasso, Femme au Coq, 1938.

Other related Picasso versions use a rooster as a symbol, placed within a scene, attentively and approvingly looking on from nearby, as a couple lies in a sexual liaison.

Pablo Picasso, Rooster, Woman and Young Man, 1967.

I first became aware of Paul Wonner’s femme au coq paintings in 2015 during a visit to the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento. Wonner and his lifelong partner William Theophilus Brown had been friends of mine and so I was particularly drawn to their paintings whenever I encountered them. The Crocker painting showed an obvious influence of Pablo Picasso and the emergence of Abstract Expressionism, particularly the work of Willem de Kooning. Wonner explores gestural painting with drips and mark-making. The large Crocker femme au coq includes in its title “#2”, alluding to at least one other version of the same subject.

Later, I did see another version, but it likewise was numbered “2”. A medium-sized painting once owned by the music composer George Perle, who taught at U.C. Davis from 1957-61; a period when Wonner was also at Davis and likely when Perle acquired the painting. On the reverse of the painting Wonner has written “2. Still Life with “Femme au Coq””. I wondered how many of these paintings there might be, and why Wonner was so intrigued with the subject. The Perle femme au coq was not dated, but Wonner wrote his 2133 Carlton Street address in Berkeley on the reverse of the canvas, which dates the painting to the period, between 1950-1956 when he attended U.C. Berkeley. He obtained various degrees there, including a BA in 1952, an MA in 1953, and an MLS (masters of library science) in 1956.

The reverse of the Perle version of Wonner’s Still Life with “Femme au Coq” showing the number “2.” and Wonner’s Carlton Street Address.

The reverse of the Gonzalez collection version of Wonner’s Still Life with “Femme au Coq” showing the number “3.” and title.

Wonner, who was born in 1920 in Arizona, had previously obtained a BA in 1941, at CCAC in Oakland, California. He was drafted into military service shortly thereafter. After the war, he moved to New York City, where he had studied at the Art Students League and attended lectures at Robert Motherwell’s studio, before returning to university studies in the Bay Area.

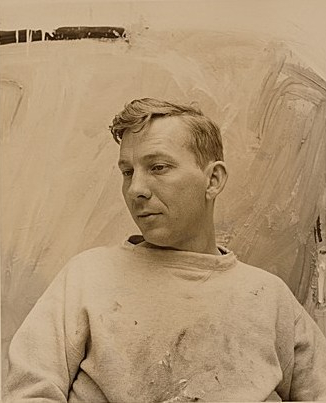

Paul Wonner, c 1955.

The Berkeley period was an exciting time for Wonner. He met William Theophilus Brown during this time and along with Brown, and other painters Elmer Bischoff and Richard Diebenkorn, he rented a painting studio on the “Shuman Block” at 2571 Shattuck Avenue, just two blocks from Wonner’s apartment on Carlton Street. From 1952, the remodeled Shattuck building housed automobile showrooms on the ground floor, with artist studios above. In time, they all became friends and influenced one another, as they came to define the Bay Area Figurative Movement, or what is sometimes called Bay Area Figuration. Ultimately, Wonner left Berkeley to work as a librarian at U.C. Davis from mid-1956 to 1960.

Historical marker at 2571 Shattuck Avenue in Berkeley, recognizing the artists that once had studios in the building.

Richard Diebenkorn, Paul Wonner, & William Theophilus Brown, Berkeley, CA, 1955. Photography by Lincoln Yamaguchi.

In addition to the Crocker and Perle paintings, other femme au coq themed paintings have been found which has only widened the mystery; just how many of these paintings are there? One was offered by Bonhams in a 2009 sale; it’s the smallest of the six paintings (that we have images of) but shares a color palette, primarily grey colors, with the Perle painting.

The de Young Museum in San Francisco also has a large femme au coq painting by Wonner in their collection (an image is available on their website). Like the Crocker version it was once owned by the painter Roland Petersen, who joined the faculty at U.C. Davis in 1956, and shows the influence of Picasso and de Kooning; however, it’s color is darker, with brown and reds predominating, suggesting it isn’t contemporaneous to the Crocker version.

A fifth femme au coq painting by Wonner was offered in a 2018 sale by Clars Auction Gallery in Oakland, California. It is numbered “3.” It has strong elements of green, blue, and white colors.

In early 2022, Scott Shields, the Associate Director and Chief Curator at the Crocker Art Museum, shared the existence of a sixth femme au coq painting in the collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art that had come to his attention as he prepared for a major retrospective of Wonner’s and William Theophilus Brown’s work, scheduled to be exhibited at the Crocker Art Museum in 2023. [fn1]

Roland Petersen, 1967.

Curiously, although Roland Petersen owned at least three of Wonner’s femme au coq paintings, he didn’t obtain them because of any interest in their thematic content. In a phone conversation with Petersen (from his home in Pacifica, 11/4/2016), the 90-year old shared that he acquired the femme au coq paintings from Wonner, when Brown and Wonner moved to Southern California in the early 1960s. According to Petersen, “Paul said I have some paintings here, why don’t you use the stretcher bars.” Fortunately, Petersen thought the paintings themselves were “too good to tear off the stretchers”. He hung them for many years then gifted them to the respective museums (Crocker, de Young, and SFMOMA).

Shields also shared a gallery announcement of Wonner’s first exhibition at the Felix Landau Gallery in Los Angeles, revealing that Wonner exhibited two femme au coq paintings in a show there in March of 1959. Still Life with “Femme Au Coq” #2 may refers to the Crocker’s painting, since the dimensions match. Notably, all twelve paintings in the exhibition were from 1955-56, including the two femme au coq paintings.

Gallery announcement from Felix Landau Gallery, 1959. Courtesy of Scott Shields.

The six versions of Still Life with “Femme au Coq” by Paul Wonner I have been able to identify with images:

CROCKER ART MUSEUM collection

Still life with “Femme Au Coq” #2.

Oil on canvas, 63 x 58.25 inches, 1955-56. Signed lower right.

Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA; gift of Roland Petersen, 1989.

DE YOUNG MUSEUM collection

Still Life with Femme au Coq

Oil on canvas, 58.5 x 61 inches, [c. 1956]. Signed lower right.

De Young / Legion of Honor, San Francisco, CA; gift of Roland Petersen, 2000.

GEORGE PERLE collection (formerly)

2. Still Life with “Femme au Coq”

Oil on canvas, 47 x 32 ½ inches, [c. 1955-56]. Signed lower right with title and inscription, verso: 2. STILL LIFE WITH / “FEMME AU COQ” / Paul Wonner / 2133 Carlton / Berkeley.

Private collection, San Francisco, CA; sold by George Perle’s estate at the Heritage Auction, November 2, 2013, Modern & Contemporary Art, Dallas, TX #5146.

MATT GONZALEZ collection

3. Still Life with “Femme au Coq”

Oil on canvas, 50 x 48 inches, [c. 1955-56]. Signed bottom left and on the reverse with title: 3. STILL LIFE WITH “FEMME AU COQ”.

Matt Gonzalez collection, San Francisco, CA; acquired from Clars Auction Gallery, Oakland, CA, Lot 6242, May 20, 2018, auction #598.

BRIAN VAIL collection

Still Life with Femme au Coq

Oil on canvas, 41 x 19 inches, [c. 1955-56]. Signed lower right and on reverse; and titled on the stretcher, verso: STILL LIFE WITH “FEMME AU COQ”.

Brian Vail collection, Sacramento, CA, acquired through the John Natsoulas Gallery, Davis, CA; previously sold by Bonhams & Butterfields, San Francisco & Los Angeles, CA, Lot 9063, Made in California auction, May 04, 2009, #16981.

SFMOMA collection

Still Life with “Femme au Coq” #1

Oil on canvas, 62.5 x 58 inches, [c. 1955]. Signed lower left.

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA; gift of Roland Petersen.

Above image copied from Breaking the Rules: Paul Wonner and Theophilus Brown by Scott A. Shields (London: Scala Arts Publishers Inc., 2023), pg. 52.

In the Perle version, Wonner turns the scene into a chaotic and decidedly unromantic one. The spoils of lovemaking spill all over the bed. The rooster stands proud on his perch, the headboard of a bed, but ultimately the woman looks frightened, as if taken literally from Picasso’s Guernica. Her arms are raised with wide open hands as if in protection from falling bombs or other atrocities. This is no scene of ecstasy, and certainly does not elevate the heterosexual ideal of couples riding off together into the sunset.

In five of the paintings for which we have images, at least one hand can be seen with the woman’s hands rendered with fingers outstretched in a way to heighten the sense of alarm. The digits on the hands have an excited flair of self-protection, again akin to Picasso’s figures in “Guernica”. These depictions suggest alarm, even warning, portending the need to act. The rooster is a signifier for this concern, as well as the woman’s expression. No doubt, something is unresolved. The painting is not about a successful sexual liaison, rather it presents something dangerous and even repugnance to the sexual act between man and woman.

Interestingly, each of the paintings depict the woman mostly in profile, looking to the West. Wonner had been in New York City prior to Berkeley, so it’s possible he references this move West or he could be commenting on Western sexual mores or expectations of the era. Of course it could simply be a coincidence.

I believe that Wonner likely explored the femme au coq theme because his own life was at odds with the ideal modernist masters had previously presented. It allowed him to explore figuration and abstracted landscape –with the bed or aftermath of lovemaking as one of the focal points, — while also allowing for comment on something deeply personal. It could be said that Wonner was proclaiming his uneasy relationship with prevailing sexual norms by disrupting the expected narrative. He isn’t announcing his homosexuality in the painting, but is certainly articulating discomfort with the idealization of heterosexuality. He doesn’t celebrate lovers, rather he presents them in chaos, awkwardly engaged with and even fearful of one another or some other force. Purposefully or not, he depicts woman in a way that rejects the central trope that lovers are enchanted with one another. In these works, Wonner is painting the societal expectation he has to contend with and be judged in contrast to; the resulting tension is palpable in the paintings.

The question remains, however, why did Wonner return to the femme au coq theme so many times? One possible explanation relates to the poet Wallace Stevens and the influence he had on many of the artist of the period. The poet Tamsin Smith brought to my attention that Stevens’ poem Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird, published in 1917 and included in his first collection, Harmonium (1920), was very popular among mid-century painters for the proposition that insight could be gained by reengaging a subject numerous times. The poem consists of thirteen loosely related separate parts, each referencing blackbirds, and many artists found inspiration in the idea that depicting the same scene repeatedly could yield important information about process, composition, and even awareness of subject matter.

Stevens had been active among the New York avant-garde scene of the teens and 1920s, having been active in Walter Arensbergs circle, so it’s not altogether surprising that artists found special meaning in his poetry. Although not explicitly about painting, Stevens’ poem was read aloud by David Park to his class at the San Francisco Art Institute, recalled Richard Diebenkorn, who would himself use the poem later with his own students.[fn2] Apparently Robert Motherwell was also influenced by it as Frank O’Hara has observed “Stevens’ Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird is almost a paradigm of Motherwell’s conception of the “series,” in which variations on a visual motif invite the artist and viewer to see things with as much ingenuity and insight [as is] available to each without violating the essential identity of the initial image.”[fn3] As noted earlier, both Diebenkorn and Motherwell had contact with, and influence on, Wonner during these formative times and this could explain Wonner’s interest in returning to the femme au coq subject matter over and over again. Certainly, if sexuality was the theme, it was a subject matter that wouldn’t be resolved by Wonner in a single painting.

Wonner confirmed his tendency to engage a subject several times before moving on to a completely new composition. In an interview on Japanese TV (Nihon), c. 1990-91. Although Wonner was speaking about one of his Dutch Still Life paintings, a realistic style he embarked on later in his career, Wonner’s remark seems equally pertinent to the “femme au coq” paintings:

“I think that I have an idea that the next few paintings I’m doing after the one that we’ve been looking at in the studio, will be similar to that, will be maybe another version of that sort of thing, developed in a different way, with a landscape and still life in the same painting. I don’t feel like this one painting says everything I want to say about that, and I think I can develop that a little bit. So, there might be two or three paintings. I seem to paint that way anyway, something gets started and goes through three or four paintings, and then something else comes in.”[fn4]

William Theophilus Brown told me Wonner had abruptly lost a librarian job at U.C. Berkeley when those making the hiring decision learned Wonner was gay. Neither Brown nor Wonner were “out” even to many of their painter friends, yet U.C. Berkeley administrators were apparently tipped off by individuals that the couple believed were friends of theirs. Thus, the slight to Wonner and Brown was even more painful. Regardless, Wonner obtained a similar job at U.C. Davis which lead to their relocation there in 1956. It led to a period of great productivity for both painters and they formed important friendships there.

Crocker Art Museum curator Scott Shields also uncovered a document from the de Young Museum in regards to Wonner’s exhibition there in March/April 1956 which helps confirm the likely date of the series of paintings as being from 1955-56. The document also definitively raises the number of paintings within the series to at least eight (it is impossible to determine if the six reproduced paintings discussed above are all accounted for in the de Young list). Curiously, one of the femme au coq paintings is listed as Figure with “Femme au Coq” rather than Still life with “Femme au Coq.” Without an image of the painting we are left to speculate how the compositional elements in that painting may differ from the others.

The de Young Museum document is important for establishing dates for the otherwise undated series of paintings. The appearance of Wonner’s Berkeley address on the reverse of one of the paintings and the Felix Landau Gallery announcement are also noteworthy. Most importantly, the style and color palette of the paintings suggests distinct temporal painting efforts. They do not convey having been painted in a single week or month. They also are not preparatory drawings; they are distinct compositions with only the Perle and Vail versions sharing a color palette. Otherwise, they differ greatly.

It is hopeful that other documentary evidence surfaces related to the femme au coq series which will clarify Wonner’s intention in rendering the subject various times. Whether or not such information is discovered, I believe the paintings we are aware of present more than a passing interest in the European trope exalting the romantic ideal of two lovers.

Matt Gonzalez

Footnotes

1. This painting was also reproduced during a television program aired by Japanese TV (Nihon), featuring Wonner, that took place circa 1990-91. The Nihon TV program was brought to my attention by Allen Wood, who is currently producing a film about William Theophilus Brown.

2. In John Elderfield’s The Drawings of Richard Diebenkorn (NY: The Museum of Modern Art, 1988) Elderfield tells the story of how David Park had Diebenkorn, his then student, make a sequence of drawings modeled after the Stevens poem. The idea was “as with the thirteen variations in the Stevens poem, each drawing had to restate, and therefore reinterpret, the nominal subject through the imaginative means of creation.” [Elderfield, pg. 13]. Wonner’s femme au coq paintings could represent a similar sequence of paintings variating the well-known European theme.

See also instagram posting by diebenkornfoundation In 1946 #Diebenkorn was one of the first WWII veterans to enroll at the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute) on the GI Bill. During his first semester he took three classes with David Park, including Line Drawing.

In class Park used poetry for quick drawing exercises. “He would say, ‘Take this subject. You have two or three minutes,’ or in the extreme, five minutes,” Diebenkorn recalled. “He got you really excited about catching the essence of an object or a poem. For example, I’ll never forget Wallace Stevens’s ‘Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird.’ He read it to us, and the class drew an exercise for each stanza. He had an endless repertoire of subjects, and each one had something marvellous that sparked you.” Park had an immense impact on Diebenkorn early on, becoming one of his most important teachers and friends.

https://gramfollo.com/tag/DiebenkornInsights

3. Motherwell did several artworks related to Stevens’ poetry. See Glen MacLeod, Painting in Poetry, Poetry in Painting: Wallace Stevens and Modern Art (New York: Baruch College, 1995), p.16; quoting Frank O’Hara, “The Grand Manner of Motherwell”, in Standing Still and Walking in New York, ed. Donald Allen (Bolinas: Grey Fox, 1975) p.178.

4. Quotation spoken by Paul Wonner, during Nihon TV (Japan) interview (original in English).

ADDITIONAL PHOTOS

Additional photos of the Perle femme au coq painting including a photo of Paul Wonner & George Perle, New York, NY, 2003 (from the book Two Men by John Jonas Gruen & Samuel Swasey):

Additional photos of the Gonzalez collection femme au coq painting:

Additional photos of the Vail collection femme au coq painting:

Images of the SFMOMA femme au coq painting copied from Breaking the Rules: Paul Wonner and Theophilus Brown by Scott A. Shields (London: Scala Arts Publishers Inc., 2023), pg. 52:

Matt a great article. Personally I am currently in the lap of an adoring woman and scared. I like Peterson’s work in general and the sexuality in these paintings works both ways.

YOU HAVE BECOME VERY ARTICULATE IN YOUR ART CRITIQUE!!

Pingback: Paul Wonner and the ‘Femme au Coq’ | Art Matters

Great article I love the anecdotes, the documentation and the whole thing of course.

great article w wonderful IMAGES – for th greater part of th 70s , I think till th fall of 78 , my own studio was in that same bldg you refer to on SHATTUCK — for a while in early 70s BILL BROWN occupied a space there too , where ELMER B was ensconced in th center of th floor in studio w great clerestory to provide xcellent light