original to The Matt Gonzalez Reader, September 12, 2018

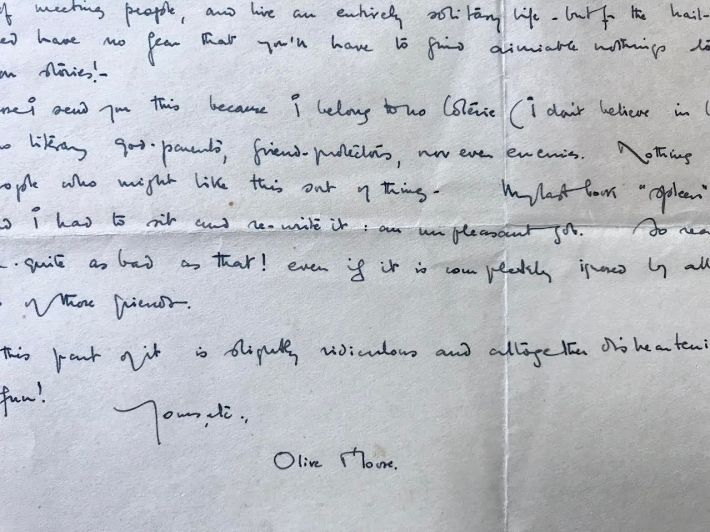

Detail of a letter written by Olive Moore, c. 1932.

FINDING OLIVE MOORE

Addressing new details that have emerged about the elusive author including a previously unpublished holographic letter

I believe only in the conscious artist. I would wish my work to be judged on the texture of my thought and the disposition of my sentences. –Olive Moore, 1933

Olive Moore Biography

Olive Moore was the pseudonym of Miriam Constance Beaumont Vaughan (born in Hereford, Herefordshire on January 25, 1901 — died in Cuckfield, West Sussex in late 1979) a writer primarily known for three novels she published between 1929 and 1932.[FN1] She has been described as an “enfant terrible of British literature” and “a cross between Virginia Woolf and Djuna Barnes, but with a more biting wit.” Moore is notorious, among those familiar with her writings, for how little information is available about her, particularly after 1934. [FN2]

Jarrolds Publishers of London published three novels by Moore: Celestial Seraglio (1929) (a novel about schoolgirls in a Belgian convent; which Moore described as autobiographical), Spleen (1930) (a novel about an English woman who flees to a Mediterranean island with her physically and mentally disabled child; simultaneously published in an American edition by Harpers & Brothers of New York as Repentance at Leisure), and Fugue (1932) (a novel about a female journalist whose romantic relationship is ending while she is pregnant and living amidst British literati in Alsace). Moore also published a collection of essays The Apple Is Bitten Again (1934) (which included an earlier separately published work on D.H. Lawrence).

What is typically repeated about Olive Moore is either inaccurate or very sparse. Her name is often given as Constance Edith Vaughan, born in Hereford, in 1904 or 1905. She is said to have been a reporter for the The Daily Sketch, and that she disappeared after writing her three novels and book of essays in 1934. It is alleged that no one is certain of the circumstances of her death, or even of the year, although it is speculated to be around 1970. One old friend of hers, Alec Bristow, emerged at the time her Collected Writings were published in 1992, to add a couple of details: she may have had an affair with the sculptor Sava Botzaris and in the early 1930s she frequented the radical bookshop owned by Charles Lahr on Red Lion Street, Holborn, London.[FN3]

The beginning of unraveling the truth about Olive Moore comes from a brief autobiographical note she wrote for Authors Today and Yesterday in 1933 (reprinted in the appendix to her Collected Writings). She confirms that she was born in Hereford, on the border of Wales. She says that “she was sent abroad to a Convent at the age of five.” She adds that as an adult “and of my own free will, I have studied art in Italy, and subjects which interest me, such as literature and language, at the Sorbonne.” [FN4]

She says that from November 1929 until May of 1930 she visited New York. It was there that the manuscript for Moore’s second book Spleen “was burnt out in a hotel fire.” She rewrote the book describing her process: “my prose is such that I have to write very slowly. I spend days reducing 500 words to 50. I loathe the easy and the slip-shot. So in a sense I memorise as I go along. I know some passages in my books word for word, because of this passion for simplifying. I remembered a great deal of Spleen, the rhythm, the construction.” [FN5]

Moore makes numerous references to being “solitary” and writes that she loves “best knowing absolutely no one”. [FN6]

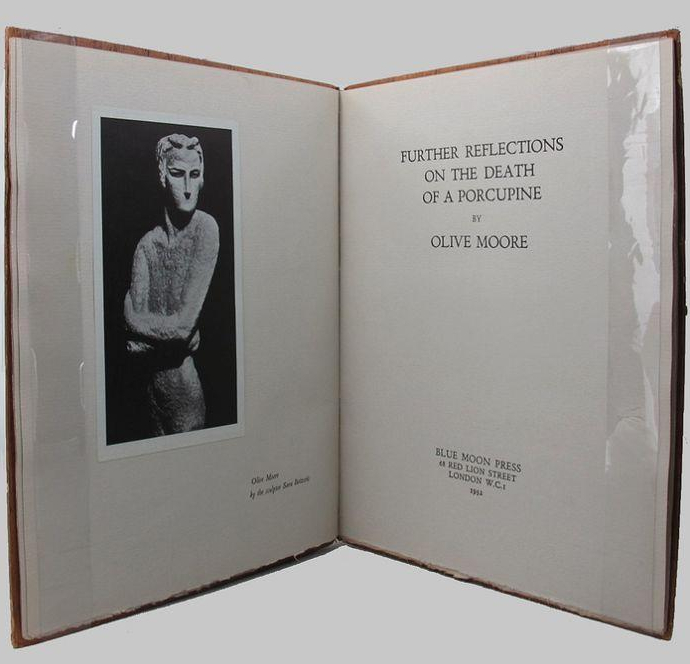

Title page of Moore’s book Further Reflections On the Death of a Porcupine showing a photograph of Sava Botzaris’s sculpture of Moore used as a frontispiece. The Botzaris image would be used again in The Apple Is Bitten Again, and the Collected Writings.

Research into Olive Moore’s life conducted in the last three years, although not widely circulated, has revealed some important details of her life while not diminishing Moore’s enigmatic reputation.

A marriage certificate, located by John Herrington along with other documentation, confirms that Moore was married in 1924 to Sava Botzaritch, commonly spelled “Botzaris” (a sculptor born in Belgrade, Serbia), at which time her occupation was listed as “dancing instructor”. It is believed the marriage ended in divorce, which explains why Alec Bristow who was friendly with her in the early 1930s, didn’t know about it. It has been confirmed that Botzaritch later emigrated to Venezuela in 1941, becoming a naturalized citizen in 1947.[FN7]

Since Moore doesn’t mention being married in the autobiographical sketch she wrote in 1933, and celebrates her solitary life, it is likely that Moore was separated or divorced by this time. Notably, a passenger record for the 1929 trip to New York (which she references in that sketch) confirms Sava Botzaritch accompanied her; in fact, they are both listed under the name Botzaritch according to Herrington’s research. From Moore’s autobiographical sketch we know she returned from her New York trip to England in the middle of 1930. So a separation or divorce likely occurred between then and 1933.[FN8]

There is recent evidence that Moore and Botzaritch had a child together, which was put up for adoption, in 1925. The child, named Peter David Beaumont Botzaritch, was adopted by a nurse in the hospital in Kennsington, West London, named Elizabeth Daisley. It is unclear why Moore and Botzaritch chose to abandon the child and much of the documentary evidence related to this event has yet to be published. [FN9] This is a significant discovery given that Moore published two novels with pregnancy and child bearing themes, despite not previously being known to have had the experience herself.

There is speculation that Moore may have worked as a stage actor (as her mother Miriam Lewes had) in the 1920s.[FN10] What can be confirmed is that she worked as a staff writer for The Daily Sketch, as early as 1924, until late 1934, where she went by the name Constance Vaughan, or “Connie” to her friends. She also contributed features and reviews to John O’London’s Weekly as early as 1923. In all, Moore is known to have written at least thirty-seven articles for The Daily Sketch as Constance Vaughan.[FN11] The Daily Sketch was a British national tabloid newspaper, founded in Manchester and John O’London’s Weekly was a literary magazine published in London. [FN12]

According to her friend Alec Bristow (quoted in the appendix to Collected Writings) who knew her in the early 1930s when she was living on Doughty Street in Bloomsbury, Moore frequented Charles Lahr’s Progressive Bookshop in Red Lion Street, London, where many local authors congregated. Bristow had favorably reviewed Moore’s Fugue in the journal Twentieth Century and she had told Lahr that she wanted to meet him. Later, Lahr and Bristow privately printed Moore’s aphorisms and observations on D.H. Lawrence, Further Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine, in 1932, in an edition of 99 numbered and signed copies under Lahr’s imprint Blue Moon Press. [FN13]

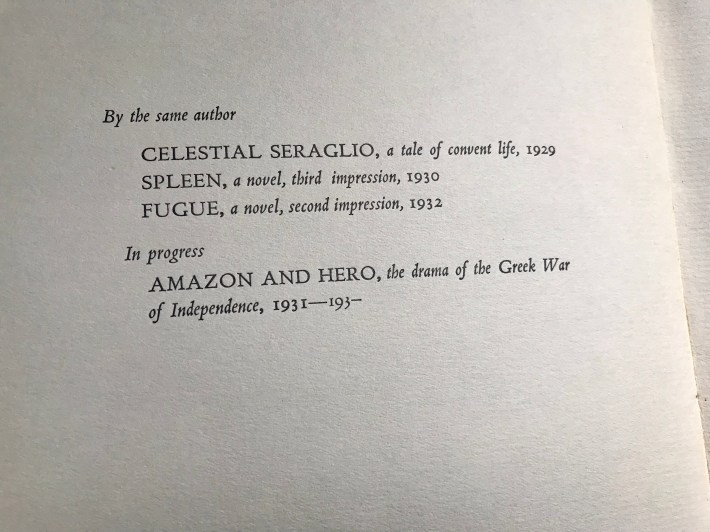

Moore told Bristow that she was working on a fourth novel tentatively titled Amazon and Hero (with a subtitle the drama of the Greek War for Independence) and Lahr listed it as “in progress” in the front matter of Further Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine, on a page where Moore lists her other publications. An additional reference to this novel appears in Twentieth Century Authors (1942) (which reprinted the autobiographical sketch Moore had written in 1933 for Authors Today and Yesterday in slightly abridged form and with this additional reference; albeit acknowledging “there is no recent word of her”). The novel was never published and it is unknown whether Moore ever completed it. [FN14]

One of the front pages of Further Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine where Moore lists her other publications and notably lists Amazon and Hero as “in progress”.

Although it has been widely reported that Moore completely retreated from literary and public life sometime in late 1934 (Moore’s last known article for The Daily Sketch was “White-Headed Women Are the Interesting Women” which appeared December 15, 1934), new research has uncovered a trove of hitherto unknown writings by Moore. In 2016, University of Southampton doctoral student Sophie Cavey discovered that Moore wrote for an industry and political monthly magazine called Scope from 1942 to 1959. Scope addressed commercial and scientific innovation within Great Britain. Moore wrote various kinds of articles for Scope and a column “Man of the Month” which profiled various persons linked to industry and invention including Le Corbusier (architect and designer), Tom Driberg (Member of Parliament), Allen Lane (founder and publisher of Penguin Books), and Rudolf Laban (a pioneer of modern dance). [FN15]

Following her mother’s death in 1964, whom Moore was living with, probate records list Moore as a “spinster”. Herrington reports that she died in 1979 in Cuckfield, West Sussex, 45 years after her last book, The Apple Is Bitten Again, was published.

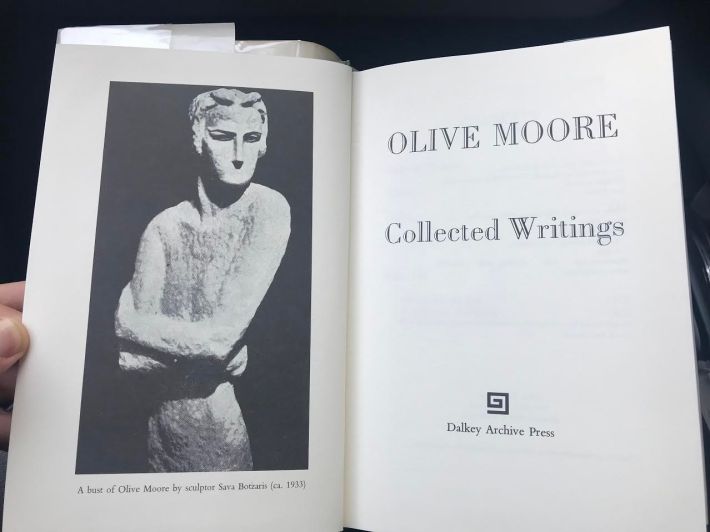

In 1992, Dalkey Archive Press republished all of Moore’s known writings (excluding the journalism) as Collected Writings.

Previously Unpublished Letter from Olive Moore to Tom Driberg, c.1932

38 Doughty Street.

W.C.1., Terminus 3501.

Dear Mr. Dryburg: I send you my book because you liked the cover and spacing, the evening of the French Players and George Munro.

I would like you to believe this an impersonal impulse — for indeed I have no social talents and an almost morbid horror of meeting people, and live an entirely solitary life — but for the hail-fellow, well met-ness of journalism. So you need have no fear that you’ll have to find amiable nothings to say about my work, should we meet on stories!

I suppose I send you this because I belong to no coterie (I don’t believe in being all propped up in a heap) and so had no literary god-parents, friend-protectors, nor even enemies. Nothing to make my work known to the one or two people who might like this sort of thing. My last book “Spleen” was burnt out — just as I had finished it, and I had to sit and re-write it: an unpleasant job. So really nothing that happens to Fugue can be quite as bad as that! Even if it is completely ignored by all the critics, their friends, and the friends of those friends.

Oh this part of it is slightly ridiculous and altogether disheartening — but the writing of it was great fun!

Yours, etc.,

Olive Moore

Reflections on Moore’s letter

The idiosyncratic minuscule handwriting is unmistakably Olive Moore’s. It matches the signature found on the 6-line First Poem / Statement broadside (single-sheet, folded once) which was published as a “Poem for Christmas 1932”, in an edition of 50 signed copies. It also matches her signature in Further Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine and in Fugue (see photos below).

Olive Moore’s signature on the cover of First Poem / Statement published by Blue Moon Press as a “Poem for Christmas 1932”.

Olive Moore’s signature in Further Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine published by Blue Moon Press in 1932.

Olive Moore’s handwriting in Fugue published by Jerrolds Publishers in 1932, inscribed to Alan Steele, a publisher and editor who also frequented Charles Lahr’s Progressive Bookshop in London.

Alec Bristow, who knew Moore in the early 1930s, says that she lived at the time on Doughty Street, (he on Mecklenburgh Street). The sender’s (Moore’s) address is listed as “38 Doughty Street”.

The reference to “the evening of the French Players and George Munro” in the first line of the letter suggests Moore and Driberg met at a theater production related to George Munro who is a major character in James Fennimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans. Munro is based on the life of Lieutenant-Colonel George Monro who was an officer in the British Army who is best known for his efforts to defend Fort William Henry during the French and Indian War.

In her letter, Moore alludes to meeting on stories, which is a journalistic reference to the fact that fellow journalists often meet while chasing after the same daily news stories. It is likely the “Mr. Dryburg” the letter is addressed to is Tom Driberg who worked as a reporter and columnist for The Daily Express from 1928 to 1943. In 1932, (the same years Moore’s third novel was published) Driberg became the sole columnist for “The Talk of London”, a society column which introduced readers to emerging socialites and literary figures. The following year he relaunched the column as “These Names Make News” (under the by-line William Hickey) which permitted him to write on social and political events. [FN16]

After his time with The Daily Express Driberg would go on to become a Member of Parliament (1942-55, 1959-74) first as an Independent and three years later as a member of the Labor Party.

Interestingly, recent scholarship by Sophie Cavey, noted above and in footnote 14 below, indicates that Moore published a “Man of the Month” profile of Tom Driberg in her column in Scope magazine.

Moore refers to sending Driberg a copy of her book Fugue, which was published in March of 1932, so the letter must date to sometime after the book’s release date. [FN17] Importantly, Moore doesn’t reference her book of essays The Apple Is Bitten Again which was published in 1934. Presumably she would have taken this opportunity to send Driberg her most recent book, which would have been more newsworthy to a columnist, as opposed to sending an “older” book. As a result, the letter likely dates from 1932-1934.

Moore’s letter again makes reference to the fact that her second book Spleen was lost in a fire, or was “burnt out” as she refers to it, necessitating a rewriting of the book: “My last book “Spleen” was burnt out — just as I had finished it, and I had to sit and re-write it: an unpleasant job.” As noted above, Moore referenced this fire in the autobiographical note she wrote for Authors Today and Yesterday in 1933 (reprinted in the appendix of her Collected Writings).

Quite tellingly, Moore once again refers to her reclusive nature: “I have no social talents and an almost morbid horror of meeting people, and live an entirely solitary life” and “I belong to no coterie (I don’t believe in being all propped up in a heap) and so had no literary god-parents, friend-protectors, nor even enemies.” It is notable that Moore is extending herself directly to a gossip columnist. Whatever misgivings she has about socializing, she clearly wants her work to reach a wider audience, and doesn’t mind making an overture that might facilitate that.

Title page of Moore’s Collected Writings, published in 1992 by Dalkey Archive Press.

FOOTNOTES:

Footnote 1—Olive Moore is often mistakenly identified as being the pseudonym of Constance Edith Vaughan (1904-1970). Research by John Herrington and published by Steve Holland in Bear Alley, 09/05/15, corrects the error.

Here is a synopsis of their research showing that Olive Moore was the pseudonym of Miriam Constance Beaumont Vaughan (1901-1979):

Where a document is referred to below, it is presumed Herrington and Steve Holland/Bear Alley were in the possession of it.

Marriage Certificate

John Herrington obtained a copy of a marriage certificate which shows that on December 24, 1924 Sava Botzaritch, sculpture, married Constance Beaumont Vaughan, a dancing instructor.

The certificate identifies Vaughan’s father as Charles Beaumont Vaughan, deceased.

It lists Constance Vaughan’s age as 21.

Passenger Record

John Herrington located a passenger record for a trip Botzaritch and Moore made to New York. Herrington only says that “both are listed under the name Botzaritch”.

Steve Holland of Bear Alley (via email 10/06/18) confirms Moore was listed as “Constance Botzaritch” and that the “SS Pennland sailed from Antwerp on 25 October 1929 and arrived in New York 5 November 1929.” Notably, November 1929 is the month and year Moore says she visited New York in the autobiographical sketch she wrote for Authors Today and Yesterday in 1933 (reprinted in the appendix to her Collected Writings).

Herrington notes that Sava Botzaritch’s age is given as 31, Moore’s as 26.

The records indicate that Sava Botzaritch was born in Belgrade, Serbia and that his wife was born in Hereford, England.

Parent’s marriage & probate records

Vaughan and Botzaritch’s marriage certificate references Vaughan’s father: Charles Beaumont Vaughan, deceased.

Further documentation obtained by John Herrington:

In 1900 Charles Beaumont Vaughan married Leah Miriam Freedberg in Yorkshire.

In the probate index Miriam Leah Beaumont-Vaughan a.k.a. Miriam Lewes died November 10, 1964 in Bournemouth.

She is listed as having been born c. 1884 according to her death registration under the name Miriam Lewes.

Probate was awarded to Miriam Constance Beaumont-Vaughan, spinster.

An entry in the Andrews Newspaper cards, related to the probate for Miriam Leah Beaumont-Vaughan, says she was an ex-actress and known as Miriam Lewes.

Miriam Constance Beaumont-Vaughan (1901-1979)

Miriam Constance Beaumont-Vaughan was born in Hereford, the birth registered in the 1st quarter of 1901.

Constance Beaumont Vaughan’s death record indicates she was born on January 24, 1901 and died in 1979. Place of death is listed as Cuckfield, Sussex.

Steve Holland of Bear Alley (via email 10/06/18) says that: “Her death was registered in December 1979 but legally a death has to be registered within six weeks unless there are questionable circumstances. So she might have died any time from October to December 1979. There appears to have been no will.”

Mirian C B Vaughan is listed in the 1901 census, presumably as an infant. (Mirian is likely a misspelling of Miriam)

The census records list her as a visitor at the household of Richard Davies, a grocer’s assistant living in Hereford.

Steve Holland of Bear Alley (via email 10/06/18) says that Constance Beaumont Vaughan’s parents are listed as Charles B. Vaughan and Miriam Vaughan, visiting actors at 33 St Luke Street, Hull, Yorkshire.

Constance Edith Vaughan (1904-1986)

Constance Edith Vaughan was born in Hereford where she lived her entire life. (Notably Miriam Constance Beaumont Vaughan was also born in Hereford).

Constance Edith Vaughan was born July 3, 1894.

She appears in the 1911 census as Edith Vaughan. She is listed in a family along with seven siblings.

Her father was a tailor maker Thomas Vaughan and her mother was Maud, who later married Thomas B. Ingram in 1924.

Constance Edith Vaughan died in 1986, not 1970.

Aditional Information about Miriam Lewes

Several entries in The London Stage list appearances by Miriam Lewes in plays performed in the 1920s.

Miriam Lewes-Vaughan, an actress born c. 1884, is listed on passenger lists.

Additional Information about Sava Botzaritch

Sava Botzaritch was actually born in 1894.

In September 1926, Anastas Sava Botzaritch, an arts student and sculpture living at “34 Beak Street, Regent Street, London W” officially registered the name A. B. Sava as a change of name. Botzaritch’s father, who had been a court painter to King Peter I of Servia, was named Cavaliere Anastras Botzartich Sava, so the name change reverted to the original family name.

Anastras Botzartich Sava emigrated to Venezuela in 1941, becoming a naturalized citizen in 1947.

The above information is taken from: https://bearalley.blogspot.com/2015/09/olive-moore.html and from email correspondence with Steve Holland.

Footnote 2—Olive Moore’s Collected Writings promotional materials; and Laura Doan & Jane Garrity, Sapphic Modernities: Sexuality, Women, and National Culture (New York: Palgrave, 2006), p.3.

Footnote 3—Olive Moore, Appendix (“About the Author”), Collected Writings (Elmwood Park, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 1992), pgs. 421-424; and Moore’s Wikipedia entry (as of 9/22/18) are two examples that presents these as the known “facts” about Olive Moore.

Footnotes 4, 5, & 6—Olive Moore, Authors Today and Yesterday, quoted in Appendix (“About the Author”), Collected Writings (Elmwood Park, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 1992), pgs. 421-422.

Footnotes 7 & 8—Research by John Herrington and published in Bear Alley, 09/05/15; Olive Moore, Appendix (“About the Author”), Collected Writings (Elmwood Park, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 1992), pg. 421.

Footnote 9—A query was posted on a UK ancestry site on August 12, 2012 by jwmulhall regarding “Constance Vaughan/Olive Moore”: “Constance Vaughan is the grandmother of my partner Sarah Daisley. Constance married the sculptor Sava Botzaris in the early 20s and they later had a baby boy called Peter, the father of Sarah. Unfortunately while a baby Peter was then put up for adoption and was taken in by Elizabeth Daisley, the Matron at the maternity hospital in Kensington.”

Recently Renee Dickinson has published the finding that Olive Moore and Sava Botzaris had a child together. Dickinson writes: “To fill in these gaps in her biography and bibliography, several students and I have conducted research on Moore’s life, and we have so far unearthed documents proving that she was married to the sculptor Sava Botzaris in 1924 and that they had a child, Peter, in 1925.”

“At this point in her life, Olive Moore, approximately twenty-two years old, was married and had given birth to a son.”

“I have recently been contacted by Vaughan and Botzaris’s grandchildren, who verified that Peter Botzaris had been adopted. They did not have any additional information on Vaughan/Moore’s life and work.”

Quoted in Renee Dickinson, “The (R)Evolution of Olive Moore, Fugue as Bridge to a New Feminist Awakening”, published in Essays on Music and Language in Modernist Literature: Musical Modernism, Edited by Katherine O’Callaghan, (NY: Routledge, 2018).

Dickinson does not reveal what information may have been obtained from the alleged Vaughan/Botzaris grandchildren, specifically what details are known of the adoption, and whether she has found any documentary evidence independent of family oral history.

Steve Holland of Bear Alley confirms the finding (via email 10/08/18): “There was a child, Peter David Beaumont Botzaritch, born in 1925. He became Peter David Beaumont Daisley, under which name his marriage (to Marianne L. Lamszus in 1948) death was registered. He died on 6 May 2014.” And furthermore: “The registration is as “Peter D. B. Botzaritch”, but his full name is given as “Peter David Beaumont Daisley” on the death registration.”

Footnote 10—Research by John Herrington and published in Bear Alley, 09/05/15 located a reference to “Olive Moore” listed in the cast of the musical Carry On, Sergeant, at the New Oxford Theatre in 1925.

Footnote 11—Alec Bristow quoted in Olive Moore, Appendix (“About the Author”), Collected Writings (Elmwood Park, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 1992), pgs. 422-424;

Renee Dickinson has researched Moore’s journalism and reviewed the collection of The Daily Sketch newspapers in the British Library: “To date, I have found thirty-seven articles written by Moore for The Daily Sketch as Constance Vaughan, as well as a few additional early articles written for John O’London’s Weekly.” Renee Dickinson, “The (R)Evolution of Olive Moore, Fugue as Bridge to a New Feminist Awakening”, published in Essays on Music and Language in Modernist Literature: Musical Modernism, Edited by Katherine O’Callaghan, (NY: Routledge, 2018).

Moore’s earliest piece in John O’ London’s Weekly is cited by Dickinson as “[title unknown]”, 21 June 1923.

Here are a few of Moore’s writings for The Daily Sketch:

“What a Woman Is Not Worth” The Daily Sketch, July 11, 1924;

“The Most Remarkable Novel” The Daily Sketch, March 6, 1925;

“How It Feels Being ME: A Modern Girl Explains Herself” The Daily Sketch, April 15, 1926;

“Modern Man Revolts” The Daily Sketch, September 21, 1926;

“Men and Monuments: What the Sentimental Sex Does With Its Memorials”, The Daily Sketch, August 17, 1933;

“White-Headed Women Are the Interesting Women”, The Daily Sketch, December 15, 1934;

see Renee Dickinson, “The (R)Evolution of Olive Moore, Fugue as Bridge to a New Feminist Awakening”, published in Essays on Music and Language in Modernist Literature: Musical Modernism, Edited by Katherine O’Callaghan, (NY: Routledge, 2018).

Footnote 12—Research by John Herrington and published in Bear Alley, 09/05/15; Wikipedia entries for The Daily Sketch newspaper and for John O’London’s Weekly.

Footnote 13—Alec Bristow quoted in Olive Moore, Appendix (“About the Author”), Collected Writings (Elmwood Park, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 1992), pgs. 422-424;

Professor David Goodway of the University of Leeds replied to a request for information about the author in the Times Literary Supplement (quoted in the appendix to Collected Writings) and confirmed that Moore was “part of Charles Lahr’s Red Lion Street circle, a literary group that gravitated towards a bookstore specializing in radical literature located at 68 Red Lion Street, Holborn.” Prof. Goodway has published a history of Lahr and his bookshop “Charles Lahr: Anarchist, Bookseller, Publisher”, London Magazine, June/July 1977, pgs. 46-55.

Footnote 14—Alec Bristow quoted in Olive Moore, Appendix (“About the Author”), Collected Writings (Elmwood Park, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 1992), pg. 422; and Twentieth Century Authors, 1942 edition, quoted in Olive Moore, Appendix (“About the Author”), Collected Writings (Elmwood Park, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 1992), pg. 424.

Footnote 15—The University of Southampton reported the discovery by Sophie Cavey of Scope articles written by Moore on December 21, 2016. Sophie Cavey is listed as a post-doctoral student on the University of Southampton website whose PhD project examines the work of Olive Moore. Cavey writes “With reference to Moore’s novels, Celestial Seraglio (1929), Spleen (1930) and Fugue (1932), I am investigating how Moore explores different modes of female disobedience as techniques of subversion that enable increased autonomy. I am interested in how Moore’s protagonists are able to confront and subvert restrictive definitions of womanhood and instead access alternative modes of subjective female identity. In the course of my research, I have also found Moore’s previously undiscovered journalism from the 1940’s and 1950’s which I am using to extend my discussion.” Cavey’s research has yet to be published.

Footnote 16—Historian David Kynaston has called Driberg the “founder of the modern gossip column” (David Kynaston, Family Britain 1951–57 (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2009) page 141.); Wikipedia entry for Tom Driberg.

Footnote 17—In the autobiographical note for Authors Today and Yesterday, published in 1933, Moore stated that Fugue was published in March of 1932.

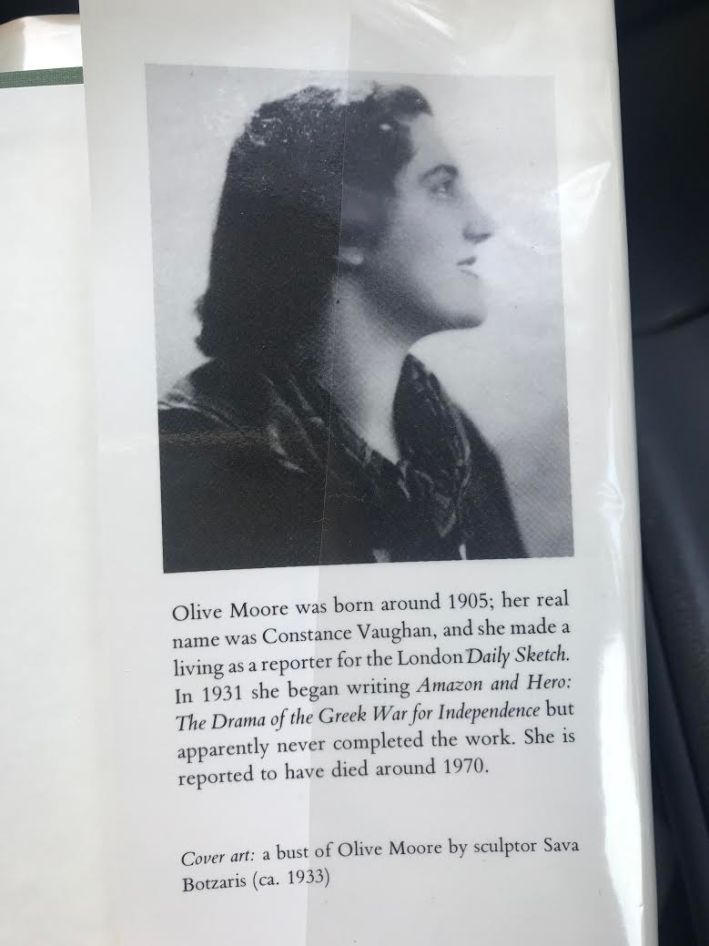

Jacket sleeve photo of Olive Moore from Collected Writings, photographer unknown. The biographical information mistakenly lists her date of birth as 1905 and year of death as c. 1970.

Another example of Olive Moore’s handwriting in a copy of Further Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine published by Blue Moon Press in 1932. Moore has noted this is a presentation copy, existing outside of the 99 numbered edition.

So glad to see so much of my original research expanded and corrected! –Steven Moore

See also Henry Handel Richardson: the Letters Volume 2: 1917-1933, edited by Clive Probyn and Bruce Steele for Henry Handel Richardson’s amusing observations on ‘C.V.’, otherwise referred to as ‘my vampire’.