first published in As It Ought To Be, March 21, 2013

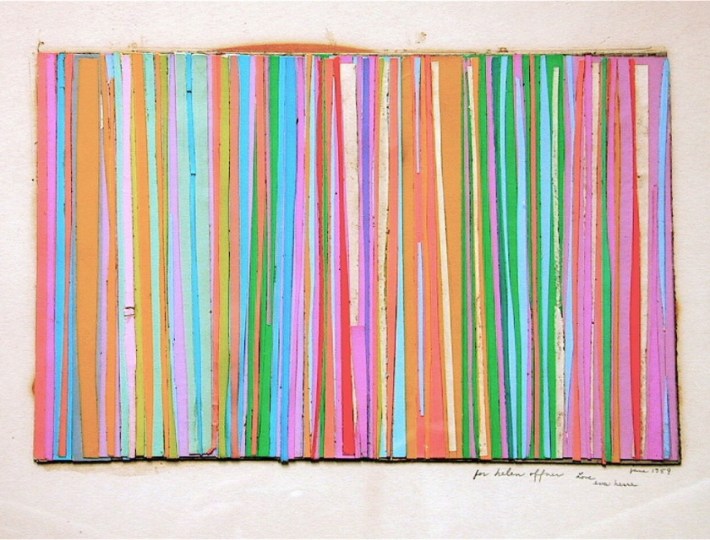

Eva Hesse, paper collage, 9 1/2 x 6 1/8 inches (1959). Private collection.

EVA HESSE AND THE COLOR COLLAGE FROM 1959

by Matt Gonzalez

“Eva was a very good collagist, a great arranger; she could take anything and arrange it.” Ellen Leelike Becker, artist who was Hesse’s first-year roommate at Yale Univ. and a classmate at Cooper Union.

This multi-colored paper collage by Eva Hesse was made while she was an art student at Yale University. Hesse inscribed it, the month she graduated in June of 1959, as a gift to the infant daughter of fellow artist Elliot Offner who was also in the art program. It marks a critical moment when Hesse is exploring texture and color and still under the influence of Josef Albers (1888-1976) the well-known Bauhaus professor who was her professor at Yale and who had also previously taught at the experimental Black Mountain College.

Eva Hesse (1936-70) earned her BFA from the School of Art & Architecture at Yale University in 1959 after studying at New York’s School of Industrial Design, Pratt Institute, Art Students League, and Cooper Union. Her studies at Yale had begun in 1957. Like Hesse, Elliot Offner (1931-2010) also was a protege of Josef Albers, earning both his BFA and MFA at Yale. He received his MFA in 1959 and joined the faculty at Smith College in 1960, remaining there until his retirement in 2004.

Hesse and Offner both studied color theory and advanced painting with Albers who retired from teaching in 1958, the year before both students graduated. Thereafter Albers remained active as a painter and lecturer. In 1963 Yale University Press published Interaction of Color, his seminal exploration on color relatedness, which presented ideas he had been formulating for decades and which were prominent in his Yale lectures. Revised and expanded editions were published in 1975 and 2006.

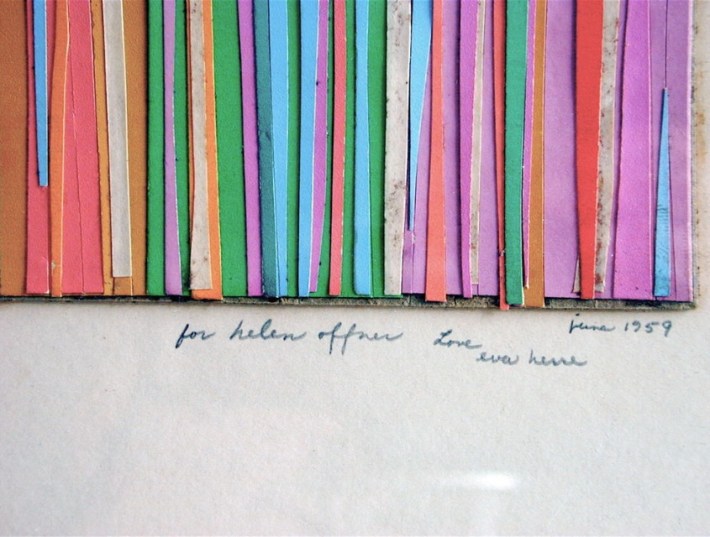

Detail of inscription: “for helen offner, Love eva hesse, june 1959″.

Josef Albers and Eva Hesse at Yale, c. 1958. Photographer unknown.

Although it is generally accepted that Hesse found Albers’ teaching rigid, his influence on her work has been the subject of much critical discussion. Art historian Jeffrey Saletnik has written Josef Albers, Eva Hesse, and the Imperative of Teaching (Tate Papers, Spring 2007). He notes: “When one reflects upon the pedagogic practice of Josef Albers, it is his colour instruction that likely first comes to mind. The former Bauhaus master’s 1963 publication Interaction of Color and its subsequent paperback editions have long been standard texts and the significance of his perception-based model of ‘color action’ in which visual relationships are developed rather than taken as given cannot be understated in terms of its importance both to art making and art instruction. Yet several of Albers’ students are known for their innovative use of material (like fibreglass and polyester resin in the case of Eva Hesse) despite having been brilliant colourists in their own right.”

“This seeming anomaly” wrote Saletnik, “can be addressed, in part, by looking more deeply at the principles that underscored Albers’ teaching.” Saletnik observed: “For Albers, colour was in constant flux. In his instruction he emphasised its relativity as material and its role in creating visual relationships, especially those causing optical estrangement. But in doing so Albers taught his students more than the interaction of colour; he instilled in them a general approach to all material and means of engaging it in design. In his teaching Albers put practice before theory and prioritised experience; ‘what counts,’ he claimed ‘is not so-called knowledge of so-called facts, but vision – seeing.’ His focus was process.”

Despite Albers’ well-known inflexibility, his Bauhaus training afforded Hesse the elbow room she needed for her own explorations, whether over color or form. Wrote Saletnik: “The Bauhaus-indebted pedagogic tenets that underlay Albers’ teaching were flexible enough so that Eva Hesse (among other of his students) could draw upon his approach to material and design in the making of vastly different work. Indeed, aside from pieces in which Hesse utilised a rectilinear format strikingly similar to Albers’ own iconic use of squares, there are few immediate visual similarities between student and teacher. Hesse’s polymorphous, tactile forms that seem to confront viewers with their materiality and the process of their crafting bear little in common with Albers’ rigid compositions. Rather, affinities between the two are expressed in terms of the process-oriented, material-based mode of instruction that constituted a major aspect of the Bauhaus Preliminary Course, dominated Albers’ teaching in the United States, and was key to Hesse’s experimentation with unconventional material. How incongruous that teaching methods often tethered (albeit superficially and in some instances erroneously) to the harsh, machined aesthetic of so-called Bauhaus Modernism might have contributed to making objects so different in appearance. The significance of Albers’ teaching to this end has been largely underestimated.”

The color collage from 1959 is a playful experiment in color and texture. Hesse created a visually appealing collage for the child of a close friend, composed of matte-colored paper strips, in tones of yellow, pink, orange, and turquoise resembling a vertical candy cane. Yet from a mature artistic vantage point, Hesse builds up the texture of the paper into a tactile three-dimensional experience, that promotes precisely the optical estrangement Albers appreciated. The composition is less controlled and direct than Albers’ own work, but Hesse’s use of colors and their interplay evokes a calmness and invitation. Albers’ influence is evident.

Although she was critical of the education she received at Yale and even of Albers, we should be careful not to give too much weight to sentiments that may not have persisted had Hesse had the opportunity to advance in age (she died in her early 30s). It is not uncommon for students who are already imagining more for themselves to find teaching stifling, yet in later years applaud it. For his part Albers considered Hesse his favorite pupil at the time, although his disdain for Hesse’s abstract expressionist painting was not disguised. Hesse is quoted, speaking of this relationship, in Catherine de Zegher’s Eva Hesse Drawing (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006): “I was Albers’s little color studyist — everybody always called me that — and every time he walked in the classroom he would ask, ‘What did Eva do?’ I loved these problems but I didn’t do them out of need or necessity. But Albers couldn’t stand my painting and, of course, I was much more serious about the painting. I had the abstract expressionist student approach and that was not Albers’s”.

Hesse spent over two full years at Yale engaging with other emerging artists and experienced teachers in aesthetic inquiries culminating in her ability to articulate and defend her own artistic preferences. She left Yale confident that she could be an artist. Lucy Lippard writes of those years in her 1976 biography Eva Hesse saying: “Although Yale was not an easy time for Hesse, though at the end of two years there she said they had been the most eventful of her life, “most traumatic–with the greatest changes inside myself.””

While the color collage from 1959 doesn’t employ Hesse’s use of polyester resin, latex, fiberglass, and other industrial materials for which she ultimately become best-known, the sculptural effect hints at her future interest. She also utilizes the glue residue as a separate material to create an opaque effect on the paper itself, again suggesting her future preoccupation with materials and a reliance on various substances in her work. The color collage is a perfect bookend to her formal art education. She concludes her academic career at Yale, and with Albers, with a collage gift that is made to a child who is likewise at the beginning of a new path.

The color collage from 1959 dates from a moment Hesse was in transition. After leaving Yale, Hesse went to New York City and obtained work as a textile designer in 1960. In 1961 her first show, a three-person show Drawings: 3 Young Americans, featuring Hesse, Donald Berry, and Harold Jacobs opened at the John Heller Gallery. In 1963 she had her first solo exhibition comprised of drawings at the Allan Stone Gallery. In 1965 she had her first sculpture exhibition, in Düsseldorf, Germany, at the Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen.

Four years later, after reaching critical acclaim, her artistic production was cut short when she was diagnosed with a brain tumor. She died the following year on May 29, 1970 at the age of 34.

At her core Eva Hesse was a process-oriented artist who understood deeply the importance of materiality in a work of art; an idea evident in this early collage from 1959.

Helen Offner, c. 1959. Photographer unknown.

Hey Matt, Thanks for your recent art reviews especially this last one on Eva Hesse. I saw your shared show at Meridian and wondered at the time whether she influenced your own collage work. cheers, April