first published in Andrew Schoultz: Age of Empire (NYC: Joshua Liner Gallery, 2016)

ANDREW SCHOULTZ: WRITING HIS OWN LANGUAGE

by Matt Gonzalez

Last month, I rose to pay my bill at a Tenderloin bar in San Francisco, and realized I’d been sitting beneath an indoor mural painted by Andrew Schoultz. One of his iconic war horses had been galloping just above my head. In San Francisco, Schoultz is ubiquitous. Before moving to Los Angeles in January of 2014, he had spent 17 years making a name for himself here. Evidenced by the many murals still visible on city streets, his persistence paid off. He not only broke out of the street and graffiti art scene and into local galleries, but started to exhibit internationally, in cities such as Toronto, Havana, Copenhagen, Milan, Cologne, Rotterdam, Mexico City, Brussels, and London.

When Schoultz arrived in California from Wisconsin, he was a twenty-three year old trying to escape the provincialism and economic depression of Milwaukee. He chose the right city for two of his passions: skateboarding and graffiti. In the ’90s, San Francisco was a mecca for these subcultures and Schoultz had already established himself as a skateboarder, having toured the U.S. with professional skaters for the four preceding years, and as a graffiti writer in the Midwest, having notched various run-ins with the law in the process.

The early ’90s saw the inception of what’s been called the Mission School art scene, which includes Barry McGee, Margaret Kilgallen, Ruby Neri, Alicia McCarthy, and Chris Johanson. Schoultz, ten years junior to McGee, arrived in San Francisco in 1997, as the movement was rapidly gaining recognition. Kilgallen, who was friendly and encouraging to Schoultz, was in the first Bay Area Now group show at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts that same year. Meanwhile, McGee was featured in the now-famous Walker Art Center exhibition in Minneapolis the following year and at Deitch Projects in New York City in 1999.

Although Schoultz’s art might not be properly labeled Mission School, it’s worth remembering that the phrase Mission School wasn’t even coined till 2002, and Schoultz was in close proximity and present at the very moment the movement was gaining momentum in the art world. Schoultz embodied the essential qualities these artists cared about. He was anti-establishment, embraced DIY ethics, and was steeped in writing graffiti and skateboard culture. In many respects, his working-class upbringing, social and political engagement, and largely self-taught aesthetics formed by drawing from comic books, made his evolution parallel, if not exactly equal to, any of the Mission School originators. Schoultz’s early theme of gentrification was the prevalent political issue of the day. The challenge was to further develop his own artistic voice, which he quickly did.

As other artists moved their art practices from the street into galleries, taking advantage of the sudden commercial interest, Schoultz strove to weave these worlds together because he didn’t subscribe to any distinction between the two. Repetitive graffiti writing had largely run its course and could no longer sustain the political commentary Schoultz wanted to make, but mural painting offered a means to evolve toward a more complex language. For Schoultz, the street equated with democratic ideals because anyone, including children, could be exposed to art without needing to be steeped in gallery culture. By contrast, the gallery was a venue for artists to present ideas and images in a setting that fostered traditional assessment and historical recognition and which allowed an artist to make a living. Schoultz wanted both.

Schoultz’s early mural work was done clandestinely, in collaboration with other artists (Zara Thustra and Aaron Noble) in San Francisco’s Nob Hill and China Basin, but he also sought legitimate opportunities to bring art into neighborhoods. His first solo murals were in the Mission District. In 2000, as part of the Clarion Alley Mural Project, which had turned a notorious heroin shooting gallery into an artistic destination, Schoultz painted “F#?KIN” Dot Com”. It was a commentary on the displacement caused by the early tech boom in San Francisco. The following year, under the tutelage of Ray Patlán, Schoultz painted “City Lights” on Balmy Alley. Patlán was known for pushing the envelope, having once painted an anti-war mural in Saigon, while serving in the U.S. Army, during the Vietnam War. He sharpened the political vision Schoultz was already manifesting. Another collaboration with Noble on 18th and Lexington Street, the mural “Generator”, has endured thirteen years.

Schoultz spent the next decade refining his craft and exhibiting widely. In 2003, he travelled to Yogyakarta, Indonesia with others, including Mission School artist Alicia McCarthy. It is there that they worked with the Apotik Komik collective on a six-week cross-cultural mural painting project, an experience which informed Schoultz’s evolving understanding of international politics as his own complexity and range further progressed. Schoultz would go on to paint murals in other cities including Toronto, Miami, Portland, St. Paul, Honolulu, and Los Angeles.

In time, Schoultz drew an art crowd around him, as Barry McGee had done. The studio he rented for many years in the Mission District was adjacent to the newly opened Guerrero Gallery, which occupied the 19th & York Street address from 2010-2013. There, Schoultz helped guide curatorial decisions and encouraged younger artists, including many who served as his studio assistants. Coincidentally, Schoultz’s York Street studio had once belonged to McGee and Kilgallen.

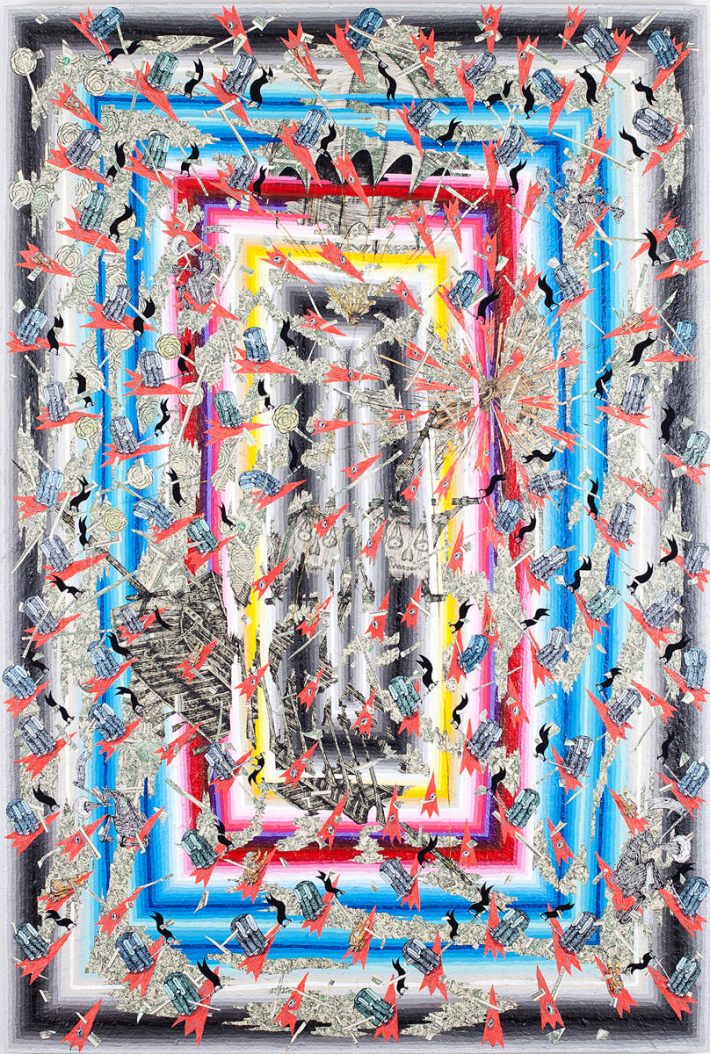

Schoultz employs a repertoire of images that have become synonymous with his work. War horses, birds, tornadoes, helmets, fallen telephone poles, supplicants in a prayer-like pose, the all-seeing eye of Providence, and a classical urn or amphora that pays tribute to the earliest functional art object, which once held water, ashes, and bones. Current social and political issues are central, but the narrative isn’t didactic, meaning it isn’t intended to exclude individual response. The body of work is remarkably consistent. He’s been exploring the same canvas for two decades, though continually taking the story deeper. Basically, the work is a patch quilt harvesting consistent themes, namely war, economic crisis, globalization, and environmental degradation. This focus is pertinent given the regrettable fact that the United States has been involved in military conflicts somewhere in the world for the better part of 25 years, corresponding to Schoultz’s adult lifespan.

Schoultz references both historic Nuremberg Chronicles of the 15th century as well as Indian and Persian miniature painting tradition from the same era. The Chronicles were part of a German map-making tradition that recorded the history of various cities in the Holy Roman Empire. In them, we get a kaleidoscope of that era’s religious and cultural warfare. In effect, Schoultz contemporizes the narrative, illustrating the pages of our modern cataclysmic tragedies. It’s all about the awful subject of war, but the compositions are rendered beautifully.

Within his dystopian vision, Schoultz’s highlights that these themes recur, repeating themselves over centuries. This begs the question of whether conflict is a fundamental human trait. Individual wars may be cultural or economic in origin, but we haven’t found a way to escape the cycle. As such, Schoultz is painting as a philosopher and historian, not simply as an artist.

This point is evident in one recent development in Schoultz’s work related to the use of color scale gradation which border and, in some cases, literally break into the compositions themselves. He started with a grey scale, as first seen in the Hosfelt Gallery show in 2014, but has now expanded into other colors, such as red and blue. The tonal gradation creates an interesting, somewhat hypnotic or Op Art effect. Its wavy line is blurry, signaling a visual softening, alluding to motion and action. Action in the painting had previously been more literal, exemplified by the painting of swirling seas or tornadoes, but these optical gradients now help propel the cataclysmic events Schoultz renders.

When he first started utilizing this blurry abstract element, Schoultz was critiquing what some have called the “new abstraction” or “new formalism” that was suddenly gaining popularity in the art world. Following widely-read essays by art critics Walter Robinson (“Flipping and the Rise of Zombie Formalism”) and Jerry Saltz (“Zombies on the Walls: Why Does So Much Abstraction Look the Same?”), many started questioning the new art trend as being too process-oriented and heavily derivative of older, dead artists. This style focuses on repetitive process, largely for its own sake. The dilution in quality seemed to be lost on the latest generation of art collectors.

Enterprising art dealers, who are often the arbiters of taste, are all too willing to promote a style that can be made relatively quickly to feed (and even foster) fresh demand. It’s almost an art market equivalent of the credit derivative swaps, whose trading cycle hastened the financial collapse of 2008, leading one to wonder whether these paintings are worth anything. Artists who want paintings to be about something — Schoultz among them — have resisted this movement, as a recycling of generic statements about post-modern society. There’s little innovative thought behind this work. By contrast, Schoultz wants art to represent – even challenge — the particular historical moment we find ourselves in. Interestingly, Schoultz’s appropriation, which began as a critique, has evolved into its own edifying vernacular.

He may have begun this as a poke in the eye of the new abstraction, but Schoultz is too serious a painter to diminish his own paintings for the sake of a joke. Schoultz doesn’t make reductive paintings, on the contrary, his narratives challenge the worldview of contemporary collectors and citizens at large. Thus, he nods to the new abstraction as a border for his own story board, by using it as a kind of decorative element, akin to the lined border some of the Nuremberg Chronicles have, or the decorative flowery borders that Persian miniaturists employed. Schoultz’s placement of the gradation on the border is, as if to say: “You are just my border — a frame through which to see my work – but my work stands for something that must be said, that must be seen.” He appropriates the language of the new formalism, but strictly to amplify his own vision.

Schoultz is in New York City again, which is also struggling with the same economic and cultural concerns facing many cities on the West Coast. I suspect his reception will be warm. It should be. His complex compositions are replete with rich iconography and a distinct dialect that is only becoming more powerful. His canvases paint a broad vision of the state of the world with a horizon that pushes the viewer to place him or herself, within or outside, a recurring plot narrative. It invites us all to consider where we stand.

Andrew Schoultz: Age of Empire

Joshua Liner Gallery, New York City

April 28 – May 27, 2016