first published in The Trial Lawyer, Winter 2019

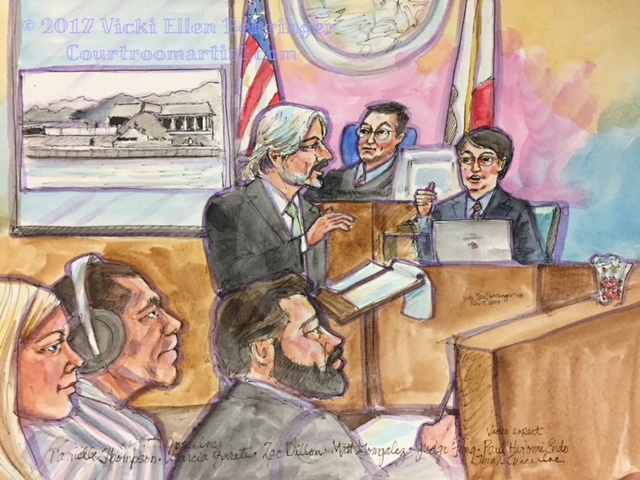

Courtroom sketch by Vicki Behringer. L-R in the foreground: Danielle Thompson (investigator), Jose Ines Garcia Zarate (defendant), Zach Dillon (paralegal/attorney); L-R in the background: Matt Gonzalez (attorney), Samuel Feng (judge), Paul Endo (expert witness).

THE GARCIA ZARATE VERDICT, 12 REASONS WHY WE WON

By Matt Gonzalez

One year ago, on November 30, 2017, a jury acquitted Jose Garcia Zarate in the murder of Kate Steinle which was alleged to have occurred on Pier 14, in San Francisco. Steinle did suffer a fatal shot that day and at that location, but a jury exonerated Garcia Zarate, finding that his handling of the firearm that discharged the bullet was an accident.

It is unlikely that the shooting death of Steinle would have gained any more than regional attention had then presidential contender Donald Trump not sought to exploit the circumstances of the case for political gain. In Garcia Zarate, an undocumented immigrant who had several felony convictions and previous deportations, Trump saw the opportunity to bolster his call for a border wall along the US-Mexico border. With a wall, Trump argued, “illegal” immigrants like Garcia Zarate wouldn’t be able to enter the United States.

Garcia Zarate’s case also became fodder for attacks on Sanctuary City policies across the country, wherein municipalities limit cooperation with federal ICE and Homeland Security agents who aggressively seek to expel undocumented persons, regardless of the length of time they have lived here. Garcia Zarate had been released by the San Francisco Sheriff, after being transferred from federal custody to resolve a 20-year old marijuana case. Because of some confusion between the federal and local authorities, Garcia Zarate was released into San Francisco, which came as a complete surprise even to him. Poor, and with only clothes provided to him from the local Goodwill Store, Garcia Zarate spent three months living along San Francisco’s waterfront, waiting for an opportunity to return to Mexico or to travel north into the State of Washington, where he had previously done construction and roofing work. It was while resting in a chair on Pier 14, that Garcia Zarate told police he found an object wrapped in a t-shirt or rags. As he unwrapped the object to see what it contained, the fatal bullet was fired.

I have previously written about why, despite the favorable verdict in the case, I believe Garcia Zarate did not receive a fair trial, “Jose Ines Garcia Zarate Did Not Receive a Fair Trial: 10 Examples”, Medium, July 2, 2018. Here, I address some of the choices the defense team made and which assured the positive outcome for our client.

12 Reasons Why We Won

- The defense team pursued an aggressive press strategy

Garcia Zarate’s defense team faced an obstacle that frequently appears in high profile cases: selective and damaging leaks by the police. Even before Garcia Zarate’s arraignment on July 7, 2015, the media was flooded with interest about the case. The press seized on one particular fact that was improperly shared with them by authorities, that Garcia Zarate had told interrogators he was shooting at seals when he unintentionally shot Steinle. This account by the police, of what the defendant had said, was inaccurate, materially incomplete, and misleading; nevertheless it was repeated widely, prejudicing the way the public viewed his case.

To contextualize it properly, Garcia Zarate had been under interrogation for several hours, from shortly before 2am until after 7am. He had already told police that he picked up an object, not knowing that the t-shirt or rags contained a gun, which subsequently misfired. They didn’t believe him. At a certain point, police asked Garcia Zarate what he was shooting at (translated into Spanish as what was he pointing at) when he handled the gun. Notably, after a long pause, he replied he didn’t know. They asked him the exact question again and after an even longer pause of about 10 seconds, Garcia Zarate said he was pointing it out there, toward seals.

Garcia Zarate was malleable under relentless police questioning (due to a 2nd grade education, long-standing mental health issues, and sleep deprivation). Anyone who interacted with him would have doubted his statement about seals, in fact, the police themselves seemed to give it little weight during the interrogation. Nevertheless, one of them repeated it to the media, and it was used to perpetuate a mocking picture of immigrants akin to Trump’s comments at his campaign kickoff, just weeks earlier: “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. They’re sending people that have lots of problems.” [FN1]

There were other issues as well.The media seized on the fact that the weapon used in the shooting had been stolen from a federal agent’s car. Repeated suggestions were made that Garcia Zarate was the burglar, despite there being substantial evidence that was very unlikely. In their reporting, the press also typically omitted a key defense fact, that the bullet had ricocheted off the concrete pier, travelling a full 90 feet before fatally hitting Steinle in the back. The improbability of intention was thus not addressed in the bulk of early press reports.

When the defense suggested the gun that fired, a SIG Sauer pistol could be discharged easily, the press quoted gun enthusiasts, who scoffed at such a remark, resulting in wide skepticism of the defense’s claim. No journalist initiated their own investigation into whether the firearm was prone to accidental discharges. Had they done so, with simple web searches, they would have found a long history of problems with this weapon.

To combat the leaks by law enforcement and the repeated omission of favorable defense evidence, the defense team pursued an aggressive press strategy, in an attempt to push back against the negative media portrayal of Garcia Zarate and right the balance. As the case neared trial we requested the trial judge make a “true name finding” of the defendant’s legal birth name, Jose Ines Garcia Zarate. He had previously been known by an AKA Juan Francisco Lopez Sanchez up until that point. This was a simple matter. We wanted the defendant to be tried under his true name. But it also served as a reset. Anyone searching the internet for Garcia Zarate would not immediately dredge up all of the Lopez Sanchez articles that mischaracterized the case. Thereafter, in the month leading up to the trial, we started generating our own press by covering different aspects of the case.In total, six separate opinion editorials were published by the defense. I authored the following: (1) Proposed Kate’s Law would not have saved Kate Steinle, July 4, 2017, SF Chronicle; (2) A gun’s history of accidental discharges, July 11, 2017, SF Examiner; (3) A ‘dangerous felon’ who was never convicted of a violent crime, July 18, 2017, 48 Hills; (4) Federal agent’s loaded gun, left unsecured in a car, killed Kate Steinle, July 21, 2017, 48 Hills; and (5) No Sanctuary for Law-Breaking Feds August 1, 2017, Beyond Chron. Francisco Ugarte authored, (6) Don’t let Trump exploit an accident to foment hate, July 21, 2017, Bayview Newspaper.

Typically, attorneys are prohibited from trying their case in the media. But the rules of professional conduct allow attorneys to respond to and defend their client in the public domain, if the publicity is not initiated by the defense. Importantly the trial judge made clear that the parties were free to speak with the press during the trial. Our request to close the proceeding for some pretrial motions, particularly related to the admissibility of the defendant’s statement, were denied. The judge had full confidence that his admonishments to the jury, to avoid press accounts during the trial, would suffice. He understood there was substantial media interest in the case and was hesitant to prohibit access.

Former California Rule of Professional Conduct 5-120(A) concerning trial publicity states (renumbered Rule 3.6, effective November 1, 2018):

A member who is participating or has participated in the investigation or litigation of a matter shall not make an extrajudicial statement that a reasonable person would expect to be disseminated by means of public communication if the member knows or reasonably should know that it will have a substantial likelihood of materially prejudicing an adjudicative proceeding in the matter. (The new rule, while substantially the same, with regard to subsection (a) now requires that a lawyer knows or reasonably should know both dissemination by means of public communication and a substantial likelihood of material prejudice will result from the extrajudicial statement.)

In a criminal case, Subsection (C) states: Notwithstanding paragraph (A), a member may make a statement that a reasonable member would believe is required to protect a client from the substantial undue prejudicial effect of recent publicity not initiated by the member or the member’s client. A statement made pursuant to this paragraph shall be limited to such information as is necessary to mitigate the recent adverse publicity. (emphasis added)

These editorials also educated many reporters, newly dispatched by their publications as trial began, who hadn’t followed the case closely until that time. There was now a repository of articles, covering key aspects of the case, they could read to get up to speed on the trial accurately. The press reports shifted as a result.

- The defense emphasized the fatal bullet was a ricochet

The police didn’t initially know that the bullet that killed Kate Steinle had ricocheted, first hitting the concrete pier before travelling another 78 feet and striking Steinle in the lower back. As a result, they questioned Garcia Zarate making the assumption that he had shot her at point-black range. Specifically, police obtained an admission that Garcia Zarate was 5 feet away when Steinle was shot and also that he had walked by her, failing to render assistance, when the truth was that he was 90 feet away from her when she was shot and thereafter left the scene in the opposite direction.

The ricochet was first discovered by the medical examiner who recognized the entry wound and damaged bullet were consistent with the bullet first hitting a hard object or surface. Dr. Michael Hunter noted: “An atypical entrance gunshot wound…”; “The wound has an oval to rectangular shape…”; and “[A] deformed medium to large caliber projectile with a flattened side surface with impact striations . . . suggesting that the projectile made contact with a possible intermediate surface prior to impacting…” (from the Medical Examiner’s report dated 8/25/15, autopsy performed 7/2/15 by Dr. Michael Hunter).

Later, the actual divet where the bullet struck the concrete surface of the pier was discovered, 12 feet from where Garcia Zarate was seated and another 78 feet away from where Steinle was standing. Rather than reevaluate their case in light of this compelling finding, the prosecution continued to press forward with a theory that Garcia Zarate had intended to shoot Steinle. The defense team repeatedly stated in the press that we knew of no murder case ever prosecuted in San Francisco history, involving a ricochet. And that “an expert marksman could not duplicate that shot if he tried”, meaning fire a shot at the ground with the intention that it bounce and then travel 78 feet in a straight line at a target.

- The defense used the physical evidence to disprove inculpatory statements made by Garcia Zarate

As noted previously, Garcia Zarate made a number of affirmations during his police interrogation that were harmful. The most damaging were that he was shooting at seals; that Steinle was shot from 5 feet away; and that he walked by her, after the shot, failing to render aid.

We were able to show these statements were unreliable once they were compared to the physical evidence. No other person on the pier that day said they had seen any marine mammals near the pier or Garcia Zarate on the edge of the pier, looking downward toward the water. The physical evidence supported that Steinle was 90 feet away from Garcia Zarate when she was shot. And the video evidence showed Garcia Zarate was seated when the incident occurred and that he fled in the opposite direction, likely not even aware that anyone had been shot.

Also, in preparation for the DAs likely reliance on these statements, during jury selection, the defense specifically asked jurors whether they would favor oral statements or physical evidence, if they had to choose between conflicting evidence. Naturally, each said they would favor the physical evidence, something we were able to remind jurors of during closing argument.

The damaging statements the defendant had acquiesced to gave the prosecution an unjustified confidence. The truth was that these statements were easy to dismiss as untrustworthy. In retrospect, any skilled trial lawyer should have hesitated to place too much importance in anything Garcia Zarate said, particularly anything he said in response to leading questions, conducted during an interrogation that lasted past 7am in the morning.

- There was substantial evidence that the SIG Sauer pistol could easily fire by accident

No one knew for certain the “trigger pull” (force needed to pull the trigger and fire the gun) of the actual gun because it hadn’t ever been tested before its use at Pier 14. This was an important issue — an easily-fired gun is more likely to be the subject of an accidental discharge. The factory specifications for a SIG Sauer P239 is 4.4 lbs in single action mode. After the gun had been submerged in salt water, the trigger pull was measured by a defense expert at 3.8 lbs, even though it is likely that submersion in water had tightened the trigger action. A prosecution expert opined that the gun could be fired with less force than the trigger pull — meaning the trigger could be manipulated with force short of placing a finger exactly on the middle of the trigger and pulling. The testimony from the prosecution witness was that a 4.4 lb trigger pull could be activated with as little as 3 lbs of force, or by analogy, a 3.8 trigger pull could be fired with 2.4 lbs of pressure applied. Additionally, a defense expert noted that the trigger activated when moved back a mere ⅛ of an inch.

The defense expert, Jim Norris, a former head of the San Francisco crime lab, testified that he had measured the trigger pull on numerous children’s squirt guns and found them to be in the area of 4 lbs of pressure, clearly not a strenuous effort. By contrast, the DA likened firing the gun to lifting a 5 lb bag of sugar with your finger. This didn’t resonate as convincing.

The SIG Sauer in Garcia Zarate’s case also had two additional features making it prone to accidents. These were the lack of a safety lever, making it perpetually ready for firing, and an unlabeled decocking lever (which had to be used to safely disengage the single-action mode). SIG Sauer’s own safety manual urges “DO NOT THUMB THE HAMMER DOWN the consequences can be serious injury or death — only and ALWAYS use the decocking lever.”

- Over federal government opposition, the defense was able to call the BLM ranger as a witness

After considerable litigation, the defense obtained the Bureau of Land Management documents related to their investigation and obtained court permission to call the BLM ranger John Woychowski, to the stand as a witness. Woychowski had reported his gun stolen 4 days before Steinle’s death. It was important that the jury see him because it helped combat the repeated mantra in the press and among conservative commentators, that none of this would have happened had an “illegal” not been released in the Sanctuary City of San Francisco. Testimony from the ranger who left a loaded firearm in an unattended vehicle, which ignited the chain of events that led to Steinle’s death, helped diffuse the narrative assigning Garcia Zarate’s sole responsibility. It allowed the jury instead to see him as an actor in a string of unintended consequences that had arguably more to do with gun control as with immigration, given that anyone visiting Pier 14 could also have stumbled upon the weapon by mistake.

Lawyers for the US Department of the Interior and the Department of Justice had argued that the defense had to publicly justify their reasons for wanting the ranger to testify via what is known as a Touhy request, which safeguards federal agencies and employees from state court mandates. We argued Touhy didn’t apply because the 6th Amendment right to call a witness supersedes the administrative rules of Touhy, citing US v. Bahamonde (9th Cir. 2006) 445 F.3d 1225. In any event, given that Woychowski was the last known person to handle the gun, his testimony on its condition was obviously relevant, thus we won the right to call him as a witness.

Two other key issues emerged during the effort to call the ranger as a witness. First, we successfully subpoenaed information from the BLM showing that Woychowski had been treated with kid gloves by SF police department inspectors. The documents also revealed that he had been travelling with a second loaded firearm, also improperly stored in his unattended vehicle. Although the court blocked the defense’s ability to tell the jury about this second gun, it did put pressure on the court to resolve a key issue in the defense’s favor.

For much of the pretrial motions, the defense had been seeking discovery related to multiple burglaries that occurred in the area of the BLM ranger’s vehicle. We wanted these other police reports to establish that Garcia Zarate had not burglarized any of the cars (no physical evidence tied him to the crimes and many items of value were stolen from various vehicles but none found in the defendant’s possession). Although the judge refused to require the DA to turn over these reports, he did ultimately tell the jury that there was no evidence Garcia Zarate was the burglar and that they should not speculate about that further.

When Woychowski did come to court, he was accompanied by two BLM attorneys, further showing the jury the federal government was closely invested in deflecting responsibility for what had tragically transpired.

Despite Section 17-6 of BLM’s safety manual stating, “All firearms, when not in active use, shall be stored in a secure place, out of sight, under lock and key. Firearms will be unloaded prior to storage.” the jury heard that Woychowski did not suffer interdepartmental BLM discipline. Had he done the same thing today, he would face criminal charges. California Senate Bill 869, approved in September 2016, makes it a crime for any person, including law enforcement, to leave an unlocked gun in a vehicle.

- Surveillance video footage capturing the event corroborated key parts of the defense case

The police obtained surveillance footage of the events involving Steinle’s shooting from a San Francisco Fire Department tug boat, approximately 1500 feet (¼ of a mile) away from Pier 14. Although the footage was grainy, it did capture where everyone was positioned at the moment of the shooting, and also appeared to show a splash in the bay where Garcia Zarate threw the gun into the water.

Significantly, the prosecution failed to carefully scrutinize the video in two key respects. First, although the events transpired in a matter of seconds, the footage obtained by police included a couple of hours of action before the shooting. When the defense team viewed it in its entirety, we discovered a group of men gathered at the very seat Garcia Zarate would later occupy. Seven or eight men spent nearly 30 minutes at that location. They could be seen picking up and putting items on the ground or placing them back into a backpack. The individuals did not appear to be tourists — they did not venture down the pier and were not sightseeing. Rather, they gathered, examining the contents of a bag and seemed to be in a huddle. Naturally, we believed these were the individuals who had discarded the gun where Garcia Zarate would later sit.

Secondly, an enhancement of the video footage showed that Garcia Zarate was bending down just before the single shot was fired. Defense expert Paul Endo noted that the speed of the footage was slower than normal video which is usually between 24-30 frames per second. Here, the fireboat video was 10 frames per second, so it didn’t capture all the body movements, but it did show the defendant leaning forward corroborating a key defense claim that he had picked up an item just before it misfired.

Both of these observations eluded the prosecution and gave the defense greater credibility with the jury.

- The defense did not pursue a mental health defense

Despite the obvious mental health issues Garcia Zarate suffered, the defense elected not to pursue a defense which would have included testimony from experts outlining a specific diagnosis in an effort to raise questions about his competence or questioning his ability to formulate intent. Why? Because nothing about Garcia Zarate’s competency affected the gravamen of his defense — that the gun was fired unwittingly and accidentally. Further, in our view, the potential risks of a mental health defense outweighed the potential benefits.

As a result, the defense averted having a prosecution expert examine the defendant, pursuant to Penal Code section 1054.3 (allowing for a prosecution-retained mental health examination when a defendant places his or her mental state in issue by offering the testimony of any mental health expert).[FN2] This would have likely resulted in a battery of tests and potentially introduced more confused statements by Garcia Zarate.

The defense team believed that mental health was relevant to understand why Garcia Zarate was easily led during police questioning. However, we were confident that no matter how the DA tried to sanitize the portion of his police interrogation she utilized in front of the jury (by excising the most incoherent parts), Garcia Zarate’s mental health issues would be apparent and the jury would consider his competency without hearing a full-blown presentation of it. (The court had ruled the prosecution could use any portion of the police interrogation). Whether the jury concluded mental health issues caused Garcia Zarate’s unreliability, or if it was due to low education, language comprehension, or sleep deprivation ultimately did not matter to us.

The prosecution was already in possession of a lengthy statement by the defendant, in which at times he displays a clear lack of comprehension. Non-sequitur word salad monologues were sprinkled throughout the defendant’s multi-hour statement. In an effort to make him seem more reasonable, and to suggest that he acted with purpose, the prosecution elected to withhold those portions of the videotaped interview from the jury. But we knew these efforts would not be enough as Garcia Zarate exuded the challenges he faced, both in his physical demeanor and during his most articulate moments.

- The defense exposed shortcomings in the police interrogation by focusing on the Spanish language portions

Although it seems obvious now, during trial the defense team realized that the police interrogation had to be stripped down to only the conversation occuring in Spanish between the defendant and the police interpreter. Viewed as typed on a page, the interrogation that occurred in English and Spanish was crammed with too many speakers. Much of the English was not carefully translated.

Once we stripped out the English and only looked at the Spanish we realized that a key question had been mistranslated, every time it was asked. The English, “Why did you pull the trigger?”, was being translated as “Why did you fire the gun?” The latter was consistent with an accidental shooting, and Garcia Zarate admitted firing the gun by accident. But pulling the trigger suggests greater voluntariness. As a result, the jury had a reason to discount the volition the prosecution needed to make this a murder case.

Pulling a trigger in Spanish is “apretar el gatillo”. However, it was repeatedly translated as “disparar la pistola”, fire the gun. Here are four examples from the transcript of Garcia Zarate’s police interrogation on 7/2/15:

(1) Police inspector: “You pulled the trigger, correct?”; Spanish interpreter: “You, uh, uh, pointed and fired the gun?”

(2) Police inspector: “So you pulled the trigger just once?”; Spanish interpreter: “So you fired one time?”

(3) Police inspector: “He just told me the truth when he pulled the trigger”; Spanish interpreter: “So you told me that you are only giving me the, you are saying the truth when you fired.”

(4) Police inspector: “And can I just ask when you pulled the trigger and you were sitting down”; Spanish interpreter: “So when you had the gun in your hand and you fired.”

- We won the instructional battles

The prosecutor lost two important instructional battles, after attempting to block key parts of the defense strategy. The prosecution argued that the court should disallow instructions related to “accident’ and offered an incorrect, but self-serving, definition of “brandishing” for purposes of the involuntary manslaughter instruction.

Accident Instruction

The prosecutor argued the defense should not get CALCRIM 510 “Excusable Homicide: Accident”. Surprisingly, the court seemed inclined to agree. After an intense argument, the judge took the issue under submission and said he would rule the following day. The possibility of not obtaining the instruction greatly concerned the defense because our entire strategy was premised on the jury being properly instructed on this defense. We offered supplemental argument in writing that evening.

CALCRIM 510 reads:

510. Excusable Homicide: Accident

The defendant is not guilty of murder or manslaughter if he killed someone as a result of accident or misfortune. Such a killing is excused, and therefore not unlawful, if:

- The defendant was doing a lawful act in a lawful way;

- The defendant was acting with usual and ordinary caution; AND

- The defendant was acting without any unlawful intent.

A person acts with usual and ordinary caution if he or she acts in a way that a reasonably careful person would act in the same or similar situation.

The People have the burden of proving beyond a reasonable doubt that the killing was not excused. If the People have not met this burden, you must find the defendant not guilty of (murder/ [or] manslaughter).

We made two very clear arguments. One, it would be error to not instruct on accident because we had offered substantial evidence in support of the instruction. However, we also offered an alternative. To this second point, the court could refuse the accident instruction we requested (despite the fact that it is an accident instruction tailored for a case where the defendant is charged with murder) and instead give a more generalized accident instruction CALCRIM 3404, which is exactly what the court decided.

CALCRIM 3404 reads:

3404. Accident

The defendant is not guilty of murder if he acted without the intent required for that crime, but acted instead accidentally. You may not find the defendant guilty of murder unless you are convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that he acted with the required intent.

The defendant is not guilty of involuntary manslaughter if he acted accidentally without criminal negligence. You may not find the defendant guilty of involuntary manslaughter unless you are convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that he acted with criminal negligence. Criminal negligence is defined in another instruction.

Although the DA sought to deny the defense any accident instruction, the resulting reliance on CALCRIM 3404 was better for the defense because it did not require the jury to carefully examine whether Garcia Zarate exercised usual and ordinary caution. This would have been averted had the DA acquiesced to the defense’s initial request for CALCRIM 510.

Brandishing Instruction (As Predicate Offense to Involuntary Manslaughter)

The prosecution also failed to prevail on the instructional battle related to a predicate offense necessary to prove involuntary manslaughter. In addition to proving “criminal negligence” (discussed below), involuntary manslaughter requires the prosecution to show the death occurred “in the commission of an unlawful act, not amounting to a felony; or in the commission of a lawful act which might produce death, in an unlawful manner, or without due caution and circumspection.” Penal Code section 192(b).

The prosecution proceeded on a theory that Garcia Zarate was committing the misdemeanor crime of brandishing a weapon as the predicate offense to involuntary manslaughter. However, in an effort to not have to actually prove Garcia Zarate actually committed the misdemeanor offense, they requested the wrong instruction.

The crime of brandishing is defined in CALCRIM 983 and requires, in part, that a defendant drew or exhibited a firearm “in a rude, angry, or threatening manner.” An enhancement to the crime of brandishing is defined in CALCRIM 984 and is relevant if the brandishing occurs: (1) in a public place; and (2) with a firearm that is capable of being concealed. If proven, it carries the additional punishment of 3-12 months (in addition to 1-6 months for the misdemeanor brandishing offense).

The prosecution requested CALCRIM 984 but not CALCRIM 983 despite the fact that the use note for CALCRIM 984 says it must be given with CALCRIM 983. Why? The simple reason is that CALCRIM 983, defining the crime of brandishing, requires that the brandishing be done in a rude, angry, or threatening manner. There was no evidence Garcia Zarate acted this way. [FN3]

Since the prosecution was proceeding on a theory that the death of Steinle occurred while the defendant was engaged in the commission of a misdemeanor brandishing, obviously the elements of that crime had to be found by the jury. It would not be enough that only an enhancement to the crime of brandishing were proven (as the DA wanted).The DA’s attempt to define brandishing so broadly obfuscated the fact that there were other misdemeanor offenses she could have used as the predicate offense.

Regardless, the prosecution would have had to prove criminal negligence, which we did not think existed here, but without a doubt the defendant did not brandish the gun on Pier 14. Once the defense won this instructional battle, we were assured Garcia Zarate would not be convicted of manslaughter.

- By arguing for 1st degree murder, the DA lost credibility with the jury

Toward the conclusion of the trial, the District Attorney informed the court that she intended to proceed on a 1st degree murder charge. The court agreed to instruct the jury on this new theory. However, this strategy backfired. No one who had been following the trial closely believed a case had been made for intentional murder.

In fact, by arguing 1st degree, the DA lost credibility. In pursuit of this theory, with no evidence that Garcia Zarate had the gun before finding it at the place where he was seated on the pier, the DA invited the jury to believe a wild speculation that Garcia Zarate had gone to the pier, which the DA called a “target rich environment”, to find someone to shoot.

There were a number of problems with this. First, the defendant had never committed a violent crime. There was no evidence that he had ever handled or fired a gun. He did not appear to have any motive for the shooting, and he certainly had not had a bad interaction with Steinle beforehand. There is no evidence Steinle and Garcia Zarate even looked at one another that day.

A theory emphasizing criminal negligence, though still not backed by the facts, would have fared better.

Even the spokesperson for the DA’s office showed evident surprise at the news the prosecution was seeking 1st degree murder. It appeared to have been a last-minute decision made by the trial DA without any prior notice to her office.

A juror wrote: “When the prosecution rested its case, it seemed clear to me that the evidence didn’t support the requirements of premeditation or malice aforethought (intentional recklessness or killing) for the murder charges. After having heard the evidence, I agreed with the defense’s opinion that the murder charges should not have been brought. The evidence didn’t show that Garcia Zarate intended to kill anyone.” —Phil Van Stockum, alternate juror, Politico.com, 12/6/17.

- We sought a not guilty verdict (not a conviction for the lesser crime of involuntary manslaughter)

Over the course of my career, I have seen lawyers lower expectations of outcomes so that they may enhance the likelihood of claiming a victory. This is especially true in murder cases, where a manslaughter conviction is generally viewed as a “win”. However, because of enhancements, particularly for the use of a firearm, which can add substantial years to a sentence, a manslaughter conviction can easily mean two decades in prison.

From the outset, the defense team said we would consider a manslaughter outcome a loss. We calculated that Garcia Zarate would likely get a 19 year prison sentence if he were convicted of involuntary manslaughter (2, 3, or 4 years for involuntary manslaughter; plus 16 months, 2, or 3 years for felon in possession of a firearm; plus 2 additional years for his prior prison commitments; and 10 years for use of a firearm).

It is also common for defense lawyers to argue a descending staircase of the law of murder in closing argument. Meaning, the lawyers begin by explaining why the case isn’t a 1st degree murder, then why it isn’t 2nd degree, then finally why it isn’t manslaughter.

Rather than take this approach, we argued that the case should not have been charged, or that at most, it should have been charged as an involuntary manslaughter. Thereafter we followed up this argument by explaining why it was not an involuntary manslaughter. There was an absence of criminal negligence because the defendant had not done anything reckless in that he did not know the object he handled had a gun in it. Additionally, the prosecution could not prove the predicate crime, in this case brandishing a gun in a rude, angry, or threatening manner.

CALCRIM 580 reads (in part):

Criminal negligence involves more than ordinary carelessness, inattention, or mistake of judgment. A person acts with criminal negligence when: 1. He or she acts in a reckless way that creates a high risk of death or great bodily injury AND 2. A reasonable person would have known that acting in that way would create such a risk.

Hence, the defense team argued that the jury could not convict of manslaughter and outlined all the reasons why this case appeared to be an accident.

It was only after carefully summarizing the evidence heard at trial, that we covered 1st and 2nd degree murder in our closing argument. In both cases it was obvious Garcia Zarate’s conduct fell outside of the elements of those offenses. If he did not know the object he was handling had a gun within it, then it could not have been a willful, deliberate, or premeditated murder.

- We picked a better jury

The key reason the defense won was that we started the trial during jury selection; from the outset, we identified prospective jurors who were open to our theory of the case. Our written questionnaire targeted key opinions prospective jurors had about guns; for instance, did they own a gun or have any knowledge about how they operated? Notably, during voir dire we asked jurors if they had ever traveled to another country. If so, we asked if they were accused of a crime while traveling, whether they would want to be judged on the facts of the case or on their foreign status.

We made clear that what happened was an awful tragedy, but that they would not have any jury verdict forms asking if they thought it was a tragedy. Their task was to strictly determine whether a crime had occurred; that an accident, no matter how awful, was not a crime.

We emphasized that Sanctuary City or any other immigration laws would not be decided in the courtroom. They would receive no verdict form asking them to express their views on immigration laws.

We asked jurors if they had ever thought about how lucky they were to be born in the United States. We told them that Garcia Zarate had first come here as a juvenile. We asked if anyone would hold it against someone for coming to this country to escape severe poverty or for trying to improve his or her life.

In effect, these questions humanized Garcia Zarate and made jurors appreciate that whatever the national policy questions the case may have sparked, none of them would be resolved in the courtroom.

The DA had the assistance of a paid jury consultant throughout jury selection. The defense did not have such assistance, but we managed to start discussing key themes that would reappear throughout the trial or continue to hover over the trial in media accounts. The rapport we established with the jurors was real and their consideration of our arguments ultimately proved how effective our voir dire had been.

Conclusion

The defense team was proud to deliver a favorable outcome in a case that drew national attention. The public saw public defenders rendering unquestionably competent legal services to an accused who was poor and unpopular. It is our hope that the result will stand as a reminder that even in sensational cases, where the facts appear to be known, everyone should hold judgment until the evidence is fully vetted in a court of law.

Although acquitted of the murder charges, Garcia Zarate was convicted of a violation of Penal Code section 29800(a)(1), being an ex-felon in possession of a firearm. During deliberations the jury asked “is there any time requirement on possession?” prompting the defense to believe they were trying to determine Garcia Zarate’s culpability for briefly holding the gun after it had fired, but before he discarded it. The trial court refused to instruct on momentary possession (a complete defense if the defendant possessed the firearm only for a momentary or transitory period to abandon or dispose of it and did not intend to prevent law enforcement officials from seizing it.) CALCRIM 2511 [FN5]. Attorney Cliff Gardner, of Berkeley, CA, is handling the state court appeal.

Following Garcia Zarate’s acquittal of the murder charges, then Attorney General Jeff Sessions brought federal gun possession charges against Garcia Zarate, something they never do where a state court defendant receives the maximum sentence in the state court for the same offense (in this case 3 years in State Prison) and otherwise has no weapons or gang history. Tony Serra, Maria Belyi, and Michael Hinckley (who was also part of the defense team in the state courts) are representing him in the federal matter. U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria has postponed the trial awaiting a decision in an Alabama case, Gamble v. U.S., currently before the U.S. Supreme Court. In Gamble, the appellant was convicted in state court of being an ex-felon in possession of a gun and thereafter plead to a similar federal charge. He appealed based on double jeopardy. Judge Chhabria has said “There is a serious possibility that the Supreme Court’s ruling in that case will require dismissal of the charges against Garcia Zarate.”

Matt Gonzalez

Footnotes

FN1 “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. They’re not sending you. They’re not sending you. They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.” (June 15, 2016, presidential announcement speech).

FN2 Penal Code section 1054.3(a) The defendant and his or her attorney shall disclose to the prosecuting attorney:

[DELETION]

(b) (1) Unless otherwise specifically addressed by an existing provision of law, whenever a defendant in a criminal action or a minor in a juvenile proceeding brought pursuant to a petition alleging the juvenile to be within Section 602 of the Welfare and Institutions Code places in issue his or her mental state at any phase of the criminal action or juvenile proceeding through the proposed testimony of any mental health expert, upon timely request by the prosecution, the court may order that the defendant or juvenile submit to examination by a prosecution-retained mental health expert.

(A) The prosecution shall bear the cost of any such mental health expert’s fees for examination and testimony at a criminal trial or juvenile court proceeding.

(B) The prosecuting attorney shall submit a list of tests proposed to be administered by the prosecution expert to the defendant in a criminal action or a minor in a juvenile proceeding. At the request of the defendant in a criminal action or a minor in a juvenile proceeding, a hearing shall be held to consider any objections raised to the proposed tests before any test is administered. Before ordering that the defendant submit to the examination, the trial court must make a threshold determination that the proposed tests bear some reasonable relation to the mental state placed in issue by the defendant in a criminal action or a minor in a juvenile proceeding. For the purposes of this subdivision, the term “tests” shall include any and all assessment techniques such as a clinical interview or a mental status examination. (emphasis added in italics)

FN3 CALCRIM 984 “Brandishing Firearm: Misdemeanor — Public Place” reads:

If you find the defendant guilty of brandishing a firearm, you must then decide whether the People have proved the additional allegation that the defendant brandished a firearm that was capable of being concealed on the person while in a public place [in violation of Penal Code section 417(a)(2)(A)].

To prove this allegation, the People must prove that:

- The defendant drew or exhibited a firearm that was capable of being concealed on the person; AND

- When the defendant did so, he was (in a public place in an incorporated city/ [or] on a public street).

FN4 CALCRIM 983 “Brandishing Firearm or Deadly Weapon: Misdemeanor” reads:

“To prove that the defendant is guilty of this crime, the People must prove that: 1. The defendant drew or exhibited a firearm in the presence of someone else; 2. The defendant did so in a rude, angry, or threatening manner; AND 3) The defendant did not act in self-defense or in defense of someone else.” (emphasis added in italics)

FN5 Momentary Possession is outlined in bracketed language of CALCRIM 2511. The instructions explains that momentary possession is a complete defense to felon in possession of a firearm if the defense proves: 1) the defendant possessed the firearm only for a momentary or transitory period; 2) he possessed the firearm to abandon or dispose of it; and 3) he did not intend to prevent law enforcement officials from seizing the firearm.

Cover of The Trial Lawyer, Winter 2019.

Portrait of Matt Gonzalez by Kyle Ranson, May 17, 2018.

Collage made by Jose Ines Garcia Zarate with case materials provided to him by attorney Michael Hinckley, 2017.

The Garcia Zarate defense team: attorneys Michael Hinckley, Matt Gonzalez, & Francisco Ugarte, November 15, 2017. Photo by Mark Iverson (not pictured are attorney/paralegal Zac Dillon and investigator Danielle Thompson).

Appeal (opening brief) filed in the Garcia Zarate matter by Cliff Gardner:

a153400_cr_brief_aob_garciazara_2f6

Sad though, don’t you think? A young woman walking with her father enjoying a beautiful morning along the waterfront gets killed. You don’t have to be a parent to understand what a nightmare that is. Zarate fired the gun. Whatever Trump’s role in bringing more than “regional attention” to the case, it’s tragic all the way around.